Abstract

This article highlights the importance of structured and systematic processes in triaging patients with minor illnesses. The main aim is to describe a model or protocol for organizing a community pharmacist’s knowledge in a manner that allows him/her to begin identifying the actual and potential drug-related problems (DRPs). We consulted standard reference textbooks and key pharmacy journals looking for common mnemonics which has been promoted as a decision aids for the supply of non-prescription medicines. Our focus was to examine each method in terms of the collecting relevant information with respect to detection of DRPs associated with self-medicating patients. The positives and negatives attributes of each method were assessed. We noticed that each of the mnemonics examine were incomplete in some area. Even for an established and popular aide-memoire, WWHAM, which is an easily remembered mnemonic to obtain a general picture of the patient’s presenting compliant does not provides adequate information for triage and recognize patient-specific medication related problems. Although other mnemonics are more comprehensive than WWHAM, they are still limited. Moreover, by no means these methods were universally use and apply in the community pharmacy practice. Alternatively, the proposed approach provides a platform for triaging a self-medication patient as well as identifying DRPs for collaborating with other health care professionals. Therefore, the STARZ-DRP is an alternative approach for conducting self-care consultation. In depth study is needed to determinate whether it is more effective than other methods for pharmacy triage service when studied in a controlled, systematic manner.

Introduction

Managing minor illnesses by self-medication is a common practice worldwide. When done correctly, self-medication benefits the individual’s health and is recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) as part of self-care.[1][2] According to WHO definition, self-medication is “the selection and use of medicines by individuals to treat self-recognized illnesses or symptoms” [1]. If a person chooses to self-medicate, he/she should be able to recognize the symptoms and determine it as a self-limited condition and suitable for self- care. In this regards, Winfield and Richards (1998) states health problems as a minor illness if a person perceived it as non-threatening and having limited duration.[3] Furthermore, he/she should be able to select an appropriate medicine, recognize and monitor its effects and side effects, and lastly he/she should follow directions to use as indicated on the label. However, this is not the case for most of the time. Instances of inappropriate use of over- the-counter (OTC) medicines by consumers[4][5][6] and associated with iatrogenic disease[7] has been reported. The inappropriate use of OTC medicines has many implications including delay or mask the diagnosis of serious illness, with increased risks of interactions and adverse drug reactions.[8]

It seems that self-medicating with non-prescription medications is a desirable choice for many peoples, but it is of concerns that most peoples do not always use non-prescription medications optimally. Now, community pharmacists (CP) are in an ideal position to give timely advice to those who are self-medicating and reinforce advice given by other healthcare professionals. They often have seen as a convenient ‘first point of call’ for advice on common symptoms and other health problems. They are also view as a gatekeeper to proper and safe use of medications. In fact, CPs and their staff do all these activities on a daily basis when customers approached them for advice about how to manage symptoms or self-treatment of minor illnesses. It is a primary objective of all healthcare providers including community pharmacists, is to improve the quality of patients’ life. All of them work to achieve two broad categories of patient outcomes, that are, (i) cure, slow, or prevent a patient’s disease; and (ii) eliminate, reduce, or prevent a patient’s symptom.[9] With regards to self-treating patients on minor illnesses, the CPs are most likely to involve in the latter category of patients’ outcomes. Perhaps they are usually the last healthcare provider with whom a patient comes in contact before using a medication. They have a key responsibility in responding to patients who are intend to self- medicate with non-prescription medications.

It has been reported that almost 20% of all drug- related admissions to a medical ward result from the use of non-prescription medication, especially OTC medications.[10] Consequently, health professionals, especially community pharmacist, need to be aware of any non-prescription medications that patients are using, in order to be able to appropriately advise them on the potential for worsening their disease process, adverse events, or drug interactions.[11] Although the role of CP in responding to customer who present with minor illness is longstanding and well-recognized, formal investigations of the extent and quality of this role had not been performed until recently. From around the late 1970s, surveys investigating symptoms presented to community pharmacist have been conducted.[12][13][14][15] Detailed examination of symptom presented to CPs show that these broad categorizations conceal a wide range of presentations requiring adequate clinical and communicative skills from the community pharmacist. Furthermore, there are number factors that make responding to symptoms in the pharmacy particularly challenging for the community pharmacist,[16] some of these includes no access to the patient medical notes or history, limited opportunities for a physical examination, detailed conversation need to be initiated, customer may have already approached another member of staff, symptoms may be presented on behalf of another person, and the customer may already have sought advice, information or treatment from another sources.

Although the DRP term has been used for quite some time[17], it was not until 1990 when first paper dealing with drug-related problems (DRPs) as a concept, first appeared[18]. The DRP was defined as “an undesirable patient experience that involves drug therapy and that actually or potentially interferes with a desired patient outcome”. This is particularly important in the context of self- medication where each person has a unique medication experience , that is, the sum of all events in a person’s life that involve medicine use.[19] It includes the person’s expectations, wants, concerns, preferences, attitudes, and beliefs, as well as the cultural, ethical and religious influences on his/her medication taking behaviour. These experiences will have a profound effect on the decisions a person makes everyday as to whether or not to take his/her medications. Once a person’s medication experience is explored, then, the CP can successfully execute his/her responsibilities of identifying, resolving, and preventing drug-related problems.

Most DRPs are avoidable and few researchers have showed that CPs are assuming an active role in preventing and solving DRPs. Westerlund,LT et.al. (2001) conducted a study in 45 volunteer pharmacies in Sweden during 10 weeks in late 1999. The study found that the most common DRPs were uncertainty about the indication for the drug (33.5%) and therapy failure (19.5%) while dyspepsia was the most frequently specified symptom (11.4%).[20] In 2005, a nationwide survey in Germany was conducted in community pharmacies to record all identified DRPs. More than a thousand community pharmacies participate in the survey had documented 10,427 DRPs (9.1 DRP per pharmacy per week). Overall, drug-drug interactions were the most frequently reported DRP (8.6%) and, according to CPs , more than 80% of identified DRPs could be resolved completely. The prescribing physician was contacted in 60.5% of all such cases. Median time needed for solving a DRP was 5 minutes.[21] A recent study showed that, in nearly 1 out of 5 encounters, direct pharmacist-patient interaction in self-medication revealed relevant DRPs in German community pharmacies.[22] The most frequent interventions were referral to a physician (39.5%) and switching patients to a more appropriate drug product (28.1%). The studies cited here have demonstrated a need for more professional attention and intervention by CPs to prevent and rectify DRPs in non-prescription consumers.

Community pharmacists can help the self-treating patients assessed the underlying conditions correctly, choose OTC product, suggesting a non- drug therapy, referral to another health professional, and ensuring correctly used of medicines. These interventions are likened to the telephone triage services offered by nurses. Perhaps, it should be realised that the function of the telephone triage nurse is to determine the severity of the caller’s complaint using a series of algorithms developed by a coordinated effort of physicians and nurses.[23][24] Here, an important aspect in the decision-making process is either to treat, not to treat, or refer the customer to another healthcare professional, most commonly the general practitioner (GP).[8]

Community pharmacists need to develop a method of information seeking and decision aid that works for them. For this purpose, the use of mnemonics and acronyms has been advocated to helps CPs remember what questions to ask a patient. There are a number of established framework called WWHAM, ASMETHOD, SIT DOWN SIR, ENCORE, CHAPS-FRAPS [25][26][27][28][29] and recently the mnemonic QuEST/SCHOLAR[30], which has been promoted as a decision aids aimed to be use as an assessment process that can assist community pharmacists in questioning patients and improving their ability to give the appropriate advice about self-care. Irrespective of the choice of any decision aids, CPs have a key responsibility in identifying, preventing, and resolving drug-related problems in patients who are intend to self- medicate with non-prescription medications. Moreover, there are concerns that pharmacy staff uses the mnemonic as a matter of rote rather than in the informed way, tailored to individual consultations.[31] As every customer is different with a unique medication experiences and therefore it is unlikely than an acronym can be fully applied. Thus, using acronym in rote fashion may miss vital information that could shape the course of action. Therefore, the objective of this article is to describe a framework called STARZ- DRP, as a decision aid to ensure that customers are counsel appropriately and triage correctly.

Methods

We consult standard reference textbooks[25][26][27] and key pharmacy journals[29][30], looking for the common mnemonics which has been promoted as a decision aids for the supply of non-prescription medicines. We believe that the clinical application of such decision aids is depending at the levels of information obtain from self-medicating patients necessary for triaging process. Therefore, each mnemonic is evaluate base on the types of information collected with regards to: (i) details about the patient’s symptom presentation; (ii) details about the patient’s medication experiences which includes allergies or sensitivities to medications, concurrent medications, coexisting disease states, action taken as well as perceptions towards medication safety and effectiveness; and (iii) details about the patient-specific factors related to medication compliance, knowledge, and cost implication on medication use. Besides these, the mnemonic is also evaluated for its ability to recognize DRPs in a busy community pharmacy. It means that the mnemonic should prompt the CPs for quick decision whether the presenting signs and symptoms is either caused by or may be treated with a drug.

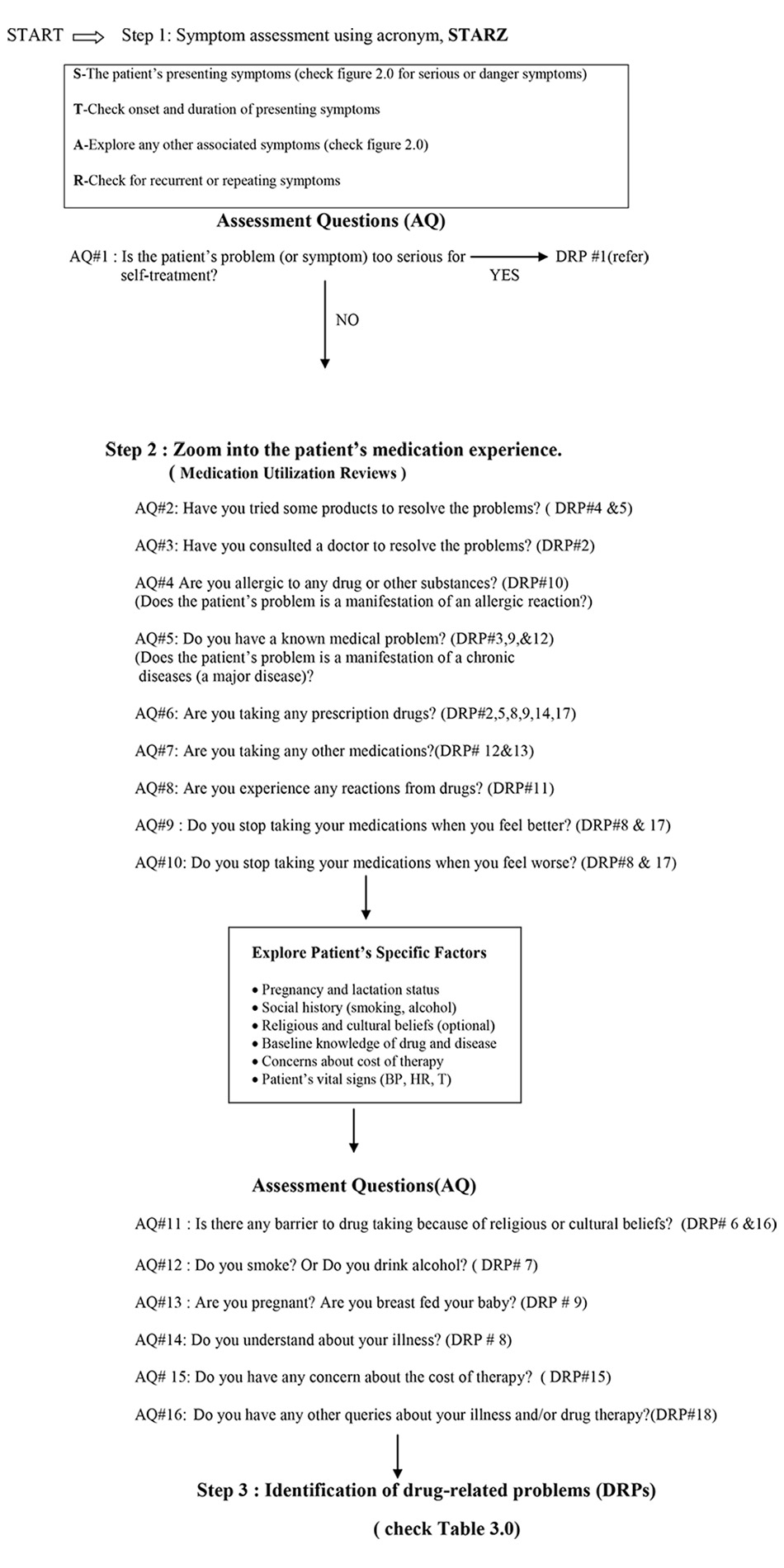

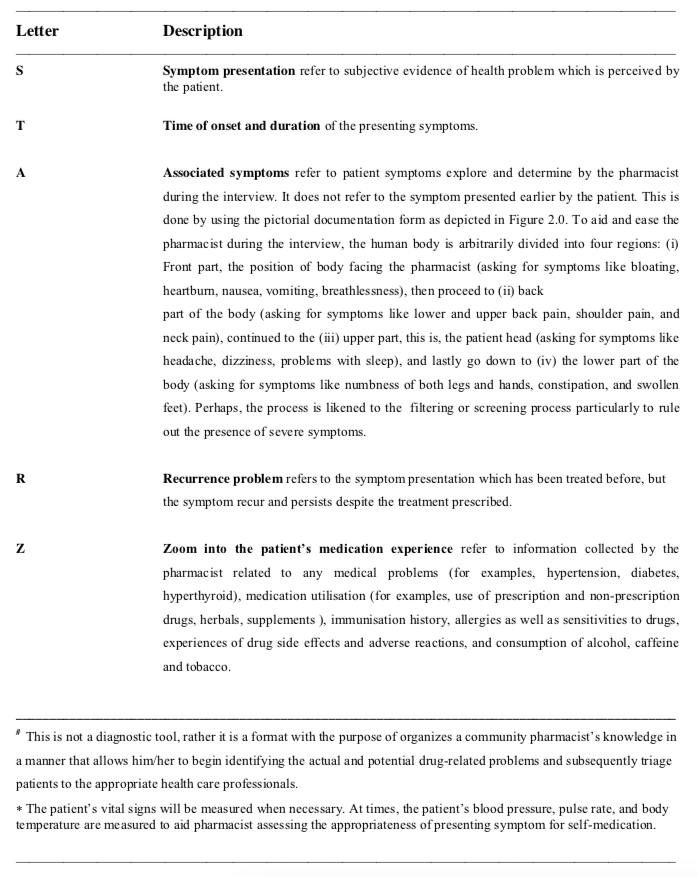

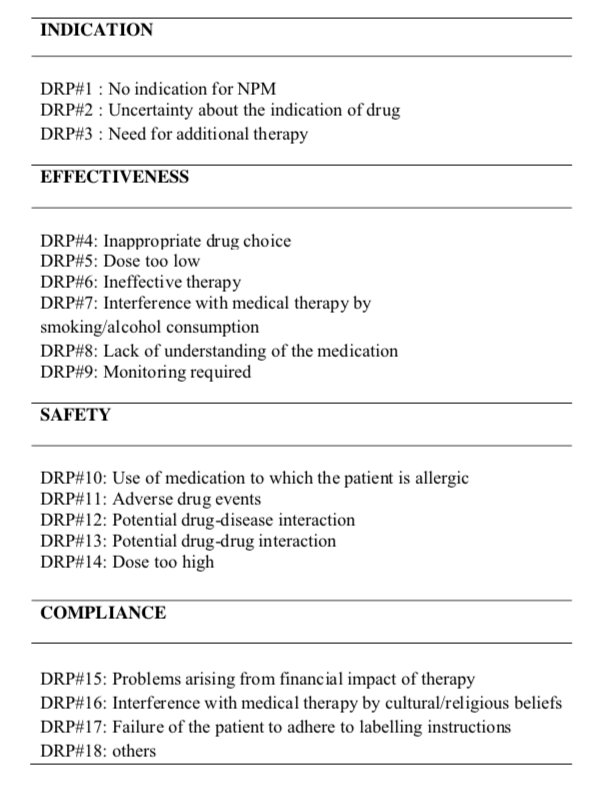

The acronym, STARZ and classification of DRPs

The provision of advice about how best to manage health issues either to recommend no action, refer, or recommend a non-prescription medicines (NPM), is essentially is a form of ‘triage’. A framework called STARZ-DRP, a three steps decision tool is develop for triaging patients in the community pharmacy setting. Each letter represents a sequential step in the decision-making process. (Table 2.0) The centrality of the decision tools to the CPs is to determine what is or is not appropriate for NPM. It contained important key assessment questions based on the principles of pharmaceutical care (Figure 1.0). In this context, Cipolle states that “ in the practice of pharmaceutical care, decisions concerning an indication are made first, then, decisions concerning effectiveness can be established, followed by safety considerations.” The compliance issues represent the ability of the patient to take the medication as intended.19 In the face of busy commercial transactions, however, it is quite difficult for CP to become aware that a patients’ symptom has a problem unless he/she set out with the intention of looking for drug-related problems. This requires careful observation and adequate questioning to identify the symptoms reported by patients, which may have a potentially serious cause. For this purpose, a set of key assessment questions is design to identify and categorize the DRPs. The categories of DRPs are summarized in Table 3.0.

Results and Discussion

Although varieties of self-care counselling strategies exist, however, each of these methods is incomplete in some area (Table 1.0) The WWHAM, a popular and an established aide- memoire used by pharmacy assistants, no doubt, it is an easily remembered mnemonic to obtain a general picture of the patient’s presenting compliant but it does not encourage elaboration for symptom assessment. There is evidence that pharmacy assistants use WWHAM as a matter of rote rather than in a informed way, tailored to individual consultations.[31] In fact, it was not optimally utilized as showed by another study that most of the consultations involved a maximum of two WWHAM items, instead out of 5 items. Of concerns, it was noticed that more than 60% of consultations did not establish whether the requestor for non-prescription medicine was using other medications concurrently.[32] These findings has implications in terms of the potential DRPs related to drug interactions and exacerbations of clinical conditions.

Although other mnemonics, ENCORE, ASMETHOD, SIT DOWN SIR are more comprehensive than WWHAM, they are still limited. To our knowledge, none of these methods was studied exclusively in the community pharmacy practice setting like WWHAM. Moreover, by no means these methods were universally use and apply in the community pharmacy practice. Similarly, the mnemonic CHAPS-FRAPS provides a detail analysis of symptoms and patient-specific factors, but it do not address when a patient should be referred nor provides indication for the recognition of DRPs. Unlike the other mnemonics, the QuEST/SCHOLAR process provides more comprehensive picture of symptom presentation as well as goes on to address the patient’s medication experiences so that the pharmacist can use this information to guide product selection or physician referral. Furthermore, this approach includes a structure for counselling the patient. Even though the process deliberately use the word quickly to

find out what is wrong with the patient, but it is of concerns, perhaps whether a busy practitioner likes the CP able to collect relevant information for the purpose of identifying, resolving, and preventing drug-related problems. On the contrary, the amount of data may vastly exceed the information needed for triaging self-medicating patients, after going through the whole QuEST/SCHOLAR process.

In the self-care context when there is need for medicines, the CP has a key role in assisting to identify the best intervention. Apart from helping to choose an OTC medicine that is safe and effective, the CP may refer patients to another health professional, most commonly to the general practitioner. Direct referrals of patients to GPs have been reported to range from 6% to 15%. [33][34][35][36] Another study found that 15% of pharmacy customers seeking advice were recommends to see their doctors, of which, 53% directly and 47% conditionally.[37] Conditional referrals is an option offered where the patients are advised to seek medical assistance if symptoms do not clear within a given timeframe. An interesting observation by Hassel et.al (1997) was that CP’s

referred their clients to GPs when they were in doubt or uncertainty about their health problems.[33] Clearly, this findings showed that CPs is keenly aware of their limits in providing care at the pharmacy. Now, perhaps, there is a need for simple aids for pharmacy triage that is not only to provide guidelines for decision-making but more importantly is to gain professional confidence.

Owing to some barriers and challenges in responding to symptoms in the pharmacy, a simple decision aids is proposed aimed for a quick screening and triaging process for patients who are needed for further assessment by other healthcare practitioners. Here, it is important to emphasize that CP has the appropriate communication skills to collect information adequately. Besides this, it is essential to have accurate knowledge of minor illnesses and its management. Any deficiencies of these aspects make the process of data collection inefficient, and may deliberately impair the triaging process. A description of each of the major steps involved in the process follows.

Step 1 : The acronym, STAR, for symptom assessment.

Either the CP or the patient can initiate the beginning of the interaction. In this situation, communication is essential in order to develop a therapeutic relationship and be receptive to create conditions conducive for conducting the interview and collecting patient data.[19] It is important to introduce personally and the patient should be addressed by his or her name.[38]

In the first step, objective information is obtained by asking the patient about his/her age and gender (usually obtained by visual observation). Then, explore the patient’s chief complaint or reason for the pharmacy visit. At this point, it is important not to confuse the patient’s self-diagnosis with patient’s symptoms. The pharmacists should act professionally and refrain from implying acceptance of the patient’s self-diagnosis. Instead, simply acknowledge the patient’s complaint and then proceed with the interview.

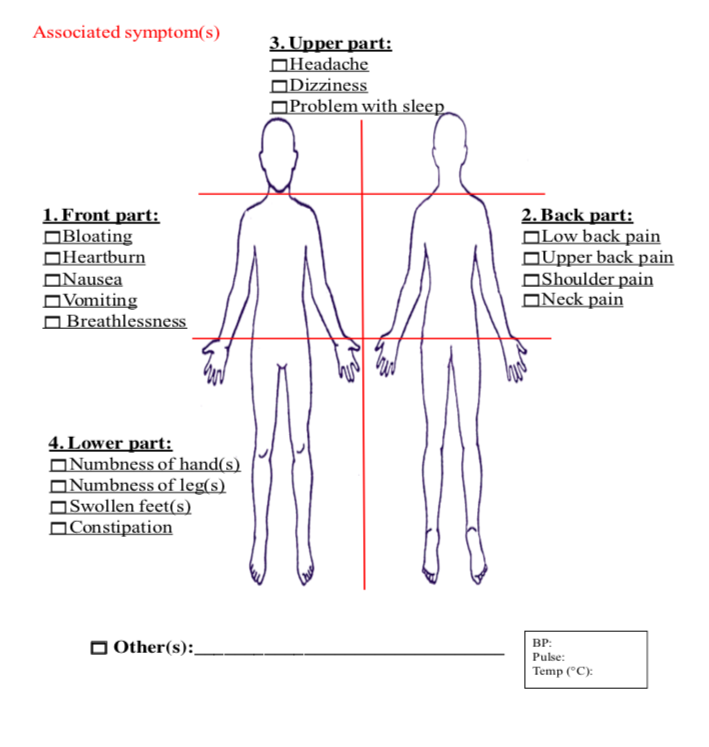

The first letter, S, represents the patient’s presenting symptoms. Besides the previously emphasized communication skills, it is essential to have accurate clinical knowledge in order to distinguish between minor and major disease. This requires careful observation and adequate questioning to identify the symptoms reported by patients. In fact, the pharmacist is provided with a checklist of serious or danger symptoms. (Figure 2.0) The second letter, T, denotes the time of onset and duration of the presenting symptoms. These objective data would provide the CP with the opportunity to clarify the history of presenting symptoms being reported. Proceed with the third letter, A, stands for the associated or related symptoms. It is therefore necessary for the CP to ask the presence (or absence) and nature of associated or related symptoms. This is best undertaken on a systematic body system basis. We design a pictorial documentation form to aid CPs during the interview process.(Figure 2.0) At this stage, it is necessary to ask the patient in detail about the symptoms. This is to ascertain that no related symptoms pertaining to the parts of body system are overlooked. Lastly, the fourth letter, R, stands for recurrence or repeated symptoms. It is important to establish whether the presenting symptom has occurred before. If it is a recurrence, it is useful to explore the course of action that has already been tried and how successful it was.

In general, referral is indicated in the following situations: (i) the CP is in doubt about the patient’s presenting symptom (the letter, S) or presence of serious or danger symptoms; (ii) the symptom is minor but persistent (the letter, T); (iii) the presenting symptom is associated with a group of symptoms ( the letter, A) ; and (iv) the symptom has recurred repeatedly (the letter, R). Obviously, if in doubt, further inquiry should be made before reaching a decision. However, in most situations, the decision is based on an accurate knowledge of minor illnesses as well as fully capable of distinguishing between minor and major disorders. Nevertheless, one’s should be remind that the STAR is not a diagnostic process but rather provides the CP with opportunity for screening or sieving the patients prior making the decision for triage. This is called as the ‘filter effect’, which is an important aspect of pharmacy triage, which can be likened to the ‘gatekeeper effect’ attributed to the telephone triage services.

Step 2 : Zoom into the patient’s medication experience.

As stated earlier, each patient has a unique medication experience describe as an individual’s subjective experience of taking a medication in his daily life. In this regards, Cipolle (2004) state “a practitioner cannot make sound clinical decisions without a good understanding of the patient’s medication experience” and urge pharmacy practitioners to take responsibility for improving each patient’s medication experience.19 For this to occur, it is essential that the CP has the appropriate communication and interviewing skills to obtain information related to the consumption of prescription and non-prescription medications, herbal products, and dietary supplements. It is also helpful to obtain information about coexisting medical conditions, allergies or sensitivities to medications, as well as immunization history, and patient’s use of alcohol, caffeine, and tobacco. This information should be evaluated in the context of the patient’s presenting symptom.

A person may engage in a number of practices or behaviours related to drug taking and drug use. These may includes self-alteration of a drug’s dosage without prescriber knowledge, use of multiple drug products, refusal to take medications because of the perceived drug’s side effects or adverse drug reactions, or seeking treatment from multiple clinics and pharmacies. The CPs, therefore, should be alert to any routine practices or behaviour that may contribute to unnecessary health risk.39 Thus, a tactful exploration of the patient’s general understanding, knowledge, and expectations concerning drug taking and use, as well as the way he actually perform daily activities, will provide CPs with enough information to identify the patient’s drug-related problems and formulate a plan for appropriate action.

Step 3 : Identification of drug-related problems (DRPs).

The scenery of DRPs should be view at the outset of the symptoms reported by patients. It can, perhaps, be scented throughout the entire courses of step 1 and 2, since this is where the CP gathers symptom-specific as well as patient-specific data and critically examine it to determine if problem exists. In the face of busy commercial transactions, however, it is quite difficult for CP to become aware that a patients’ symptom has a problem unless he/she set out with the intention of looking for drug-related problems. As studied by Currie et.al.(1997), the detection of DRPs were increased after the CPs went through a training program. A 40-hour pharmaceutical care training program was developed and presented to pharmacists, and patients were randomly assigned to receive either traditional pharmacy services or pharmaceutical care, consisting of initial work-up and follow-up with documentation in a patient record. The findings showed that patients receiving pharmaceutical care were more than seven times as likely to have any problems identified, more than eight times as likely to have an intervention performed, and more than eight times as likely to have a drug-related problem identified than were patients receiving traditional pharmacy services only.[40]

It is certain that we need to have knowledge about the patient’s total drug use to address issues regarding DRPs. In addition, we need to explore other factors influencing the patient’s use of medicines. In the entire course of self-medication practices there are three main processes where a DRP can be generated: (i) patient’s presenting symptom ;(ii) patient’s drug utilization pattern; and (iii) patient’s specific factors that may impede and influence the patient’s medication taking behavior. In practice, however, it may not be feasible to begin identifying medication problems unless the patient is interview thoroughly about drug use and relevant aspects to uncover potential and actual DRPs. In fact, this is a method currently used in clinical practice, especially by clinical pharmacists in hospitals and nursing homes,[41][42] and a high proportion of the DRPs identified in the interviews were of major clinical significance.[43]

The true prevalence of DRPs in self-medicating patients is unknown. Therefore, a tactful exploration of the patient’s presenting symptom, drug taking practices and behaviors, as well as the way patient actually cope with his/her illness, will provide pharmacists with enough information to identify the DRPs and formulate a plan for appropriate action. The categories of DRPs listed in Table 3.0 is an addition to the seven categories proposed by Cipolle et.al (1998)[19] We concur with Cipolle that the categories apply across all patient, practitioner, and institutional variables. The additional items in the list are mainly to take into account the three main processes of self- medication practices mentioned earlier. In this context, the order of how the DRP were identified is important. In the practice of pharmaceutical care for minor illnesses, decisions’ concerning an indication for NPM is made first. By asking the key questions as depict in Figure 1.0, then, possible causes of DRPs are determined. Most importantly, this will guide the CPs in the process of problem solving during the encounter with patients. In addition, reasons for referral and effective care plan can be establish. Finally yet importantly, the process may seem lengthy and tedious, but once it becomes habitual and is perform routinely, the process can be both comprehensive and time-effective.

Currently, a demonstration project of the STARZ- DRP model is been studied among a group of community pharmacies in Penang. Ten retail pharmacies were recruited in the study that comprises of five control and five study pharmacies. All pharmacists taking part in the study was instructed to obtain information on the patient drug use during a natural dialogue and to apply the proposed model consistently but still with professional judgment. Hence, the model was not meant to be use literally but to be adjusted to the actual patient and his/her medication experience. The control group continues carry out their usual care while the study group exposed to the elements of pharmaceutical care that comprises of patient assessment, care plan, and monitoring. The STARZ-DRP was the assessment part of the pharmaceutical care. Patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria and complaints of headache, dysmenorrhoea, back pain, constipation, dyspepsia, nasal symptoms, sore throat, cough and high temperature are invites to participate in the study. Apart from the documentation of the patient’s DRPs, a group of experts’ panel evaluate the appropriateness for triaging patients by community pharmacists. The group comprises of 10 general practitioners and 10 community pharmacists. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study of this kind, an attempt to provide a documentation of the pharmaceutical care practice for minor ailments.

Conclusions

This article highlights the importance of structured and systematic processes in triaging patients with minor illnesses. The STARZ-DRP introduces a format with the purpose of organizes a community pharmacist’s knowledge in a manner that allows him/her to begin identifying the actual and potential DRPs. However, it should be noted that STARZ-DRP is not intended to advocate self- medication, but to provide a platform for collaboration with other health care professionals in order to promote rational use of medicines. Again, it is important to emphasize the importance of an effective communication skill and accurate clinical knowledge to distinguish between minor illness and major disease. Further study is needed to determinate whether STARZ-DRP is more effective than other methods for pharmacy triage service when studied in a controlled, systematic manner.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Universiti Sains Malaysia for providing the Research University (RU) Grant to fund this research. Under this RU grant, we are currently conducting a research project entitled “Establishing and implementing the philosophy of pharmaceutical care in the community pharmacy practice – A Malaysian perspective. ” (Grant number: 1001/PFARMASI/8120234)

References

- WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION. The role of the pharmacist in self-care and self-medication. Hangue: World Health Organization.1998

- World Self-Medication Industry. WSMI declaration on self-care and self-medication(2006) Available at : http://www.wsmi.org/pdf/bali_declaration.pdf Accessed on : 18 September 2010

- Winfield,A.J. and Richards,R.M.E. Pharmaceutical practice. 2nd. Ed. Hong Kong. 1998

- Ajuoga, E., Sansgiry,S.S., Ngo,C. Use/misuse of over-the-counter medications and associated adverse drug events among HIV-infected patients. Res Soc Admin Pharm, 2008 ;4(3): 292-301

- Biskupiak,J.E., Brixner,D.I., Howard,K., Oderda, D.M Gastrointestinal complications of over-the- counter nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother , 2006; 20 (3), 7–14

- Sorensen,H.T.,Mellemkjaer,L.,Blot,W.J. et al., Risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding associated with use of low-dose aspirin, Am J Gastroenterol , 2000; 95 (9): 2218–2224

- Fored,C.M.,Ejerblad,E.,Lindblad,P., et al., Acetaminophen, aspirin, and chronic renal failure, N Engl J Med , 2001; 345 (25):1801–1808

- Pray, S.W. Non-prescription Product Therapeutics, 2nd. Eds. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, MD 2006 pages 18-29

- Hepler,C.D., Strand,L.M. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Amer J Hosp Pharm, 1990; 47: 533-543

- Caranasos, G. J., Steward, R. B., & Cluft, L. E. Drug-induced illness leading to hospitalization. JAMA,1974; 228, 713-717.

- Pharand, C., Ackman, M. L., Jackevicius, C. A., Paradiso-Hardy, F. L., & Pearson, G. J. Use of OTC and herbal product in patient with cardiovascular disease. Ann Pharmacother, 2003; 37: 889-904

- Bass, M. The pharmacist as provider of primary care. Canadian Medical Assosiation Journal,1975; 12, 60- 64

- Boyland, L. J. Advisory role of the pharmacist. The Pharmaceutical Journal, 1978; 221, 328

- D’Arcy, P. F., Irwin, W. G., Clarke, D., Kerr, J., Gorman, W., & O’Sullivan, D.The role of the General Practice Pharmacist in Primary Health Care. The Pharmaceutical Journal,1980; 223:539-542

- Smith, F. J., & Salkind, M. R. Presentation of Clinical Symptoms to Community Pharmacist in London. Journal of Social Administrative Pharmacy, 1990; 7: 221-224

- Waterfield, J. Community Pharmacy Handbook. 2008 London, Chicago: Pharmaceutical Press.

- Dick, M. L., & Winship, H. W. A cost effectiveness comparison of a pharmacist using three methods for identifiying posible drug related problems. Drug Intell Clin Pharm,1975; 9(5): 257-262.

- Strand, L. M., Morley, P. C., Cipole, R. J., Ramsey, R., & Lamsam, G. D. Drug-related problems: their structur and function. Ann Pharmacother,1990; 24(11): 1093-1097.

- Cipolle, R.J., Strand, L.M., Morley. Pharmaceutical Care Practice: The Clinician’s Guide. 2nd. ed.2004. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Westerlund LT, Marklund BR, Handl WH, Thunberg ME, and Allebeck P Nonprescription drug- related problems and pharmacy interventions. Ann Pharmacotherapy, 2001; 35 (11) : 1343-1349

- Hämmerlein A, Griese N, Schulz M. Survey of Drug-Related Problems Identified by Community Pharmacies. Ann Pharmacotherapy, 2007;41(11):1852-1832

- Griese N, Berger K, Eickhoff C.Prevalence of drug-related problems in self-medication (OTC use). Pharmacotherapy,2009;29(Suppl); 39e

- Sara Courson What is Telephone Nurse Triage? Connection magazine. Available at : < http: // www. Conectionsartclemagazine.com /articles/5/090.html> Assessed on : 20 September 2010

- O’Connell JM, Towles W, Yin M, Malakar CLPatient Decision Making: Use of and Adherence toTelephone-Based Nurse Triage Recommendations. Med Decis Making,2002; 22(4): 309-317

- Blenkinsopp,A.,Paxton,P.,Blenkinsopp,J. Symptoms in the pharmacy: A guide to the management of common Illness, 5th. Eds. 2005. Blackwell Publishing,Oxford,UK. pages 1-13

- Edwards,C., Stillman,P. Minor illness or Major disease? The clinical pharmacist in the community. 4th. Eds. 2006. Pharmaceutical Press, London. pages 1-10

- Rutter,P. Community pharmacy. Symptoms, Diagnosis and Treatment. 2004. Churchill Livingstone. An Imprint of Elsevier Limited. pages ix – xi.

- Rutter PM, Horsley E, Brown DT. Evaluation of community pharmacists’ recommendations tostandardized patient scenarios. Ann Pharmacother, 2004; 38:1080–5.

- McCallian DJ, Cheigh NH. The pharmacist’s role in self-care. J Am Pharm Assoc, 2002; 42:S40–1

- Shauna M B, Kirby J,Conrad WF. A Structured Approach for Teaching Students to Counsel Self-care. Patients. Am J Pharm Educ, 2007;71(1): 1-7

- Watson,M.C., Bond,C.M. The evidence based supply of non-prescription medicines: barriers and beliefs. Int J Pharm Prac, 2004; 12: 65-72

- Watson,M.C., Hart,J., Johnson,M. Bond,C.M. (2008) Exploring the supply of non-prescription medicines from community pharmacies in Scotland. Pharm World Sci, 2008; 30:526-535

- Hassell K, Noyce PR Rogers A, Harris J and Wilkinson J A pathway to the GP: The pharmaceutical consultation’ as a first port of call in primary health care. Family Practice, 1997 14(6): 498-502

- Seston L, Nicolson M, Hassell K, Cantrill J and Noyce P Variation in the incidence, presentation and management of nine minor ailments in community pharmacy. Pharm J, 2001; 266: 429-432

- Bissell, P, Ward PR and Noyce P Variation within community pharmacy: 3. Referring customers to other health professionals. J Soc Admin Pharm, 1997; 14(2): 116-123

- Tully MP, Hassel K and Noyce P Advice-giving in community pharmacies in the UK. J Health Services Res Policy, 1997; 2(1): 38-50

- Marklund B, Karlsson G and Bengtsson C The advisory service of the pharmacies as an activity of its own and as a part of collaboration with primary health care services. J Soc Admin Pharm, 1990; 7(3): 111-116

- Berger BA. Communication skills for pharmacists: Building relationships and improvise patient care. Washington : American Pharmaceutical Association, 2005

- Azmi S.Drug counseling: The need for a systematic approach. J Pharm Technol, 1993 9: 6-9

- Currie JD, Chrischilles EA,Kuehl AK, Buser RA.Effect of a training program on community pharmacists’ detection of and intervention in drug-related problems. J Am Pharm Assoc,1997; Mar- Apr, NS37(2):182-191

- Furniss,L.,Burns,A,Craig,S.K.,et.al. Effects of a pharmacist’s medication review in nursing homes. Randomised controlled trial. Br.J.Psychiatry,2000; 176: 563-7

- Kaboli,P.J.,Hoth,A.B.,McClimon,B.J.,et.al.Clinical pharmacists and inpatient medical care: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med,2006;166:955-64

- Viktil,K.K.,Blix,H.S.,Moger,T.A.,et.al. Interview of patients by pharmacists contributes significantly to the identification of drug-related problems(DRPs). Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf,2006;15:667-74

- van Mil JWF, Westerlund LT, Hersberger KE, Schaefer MA. Drug-related problem classification systems. Ann Pharmacother,2004; 38: 859-867

Please cite this article as:

Azmi Sarriff, Nazri Nordin and Mohamed Azmi A Hassali, STARZ-DRP: A Step-by-step Approach for Pharmacy Triage Services. Malaysian Journal of Pharmacy (MJP). 2011;9(1):311-324. https://mjpharm.org/starz-drp-a-step-by-step-approach-for-pharmacy-triage-services/