Abstract

Introduction: Enteral feeding is a type of nutritional support for critically ill patients who are unable to tolerate oral feeding. It is vital to ensure that nurses practise proper administration techniques via enteral feeding tubes (EFT) to ensure that medications can be delivered safely and effectively. Objective: This study aims to assess the knowledge and practice of nurses on medication administration through EFT. The association between demographics and knowledge was also explored. Method: This study is a cross-sectional, self-administered, content-validated, pre-tested questionnaire survey involving all nurses who worked in the ward setting at Hospital Queen Elizabeth II from August to December 2020. Result: A total of 409 questionnaires were sent out with 252 responses received. The majority of respondents were female (n = 240, 95.6%) with a median working experience of 84 months (interquartile range of 44 months). Most nurses knew that the immediate-release dosage forms (n = 237, 94.4%) may be crushed and administered through EFT. Similarly, most nurses were aware that sublingual nitroglycerin (GTN) tablets should not be crushed (n = 232, 92.8%) and that nystatin suspension should not be administered via EFT (n = 212, 85.1%). However, about half of the nurses responded incorrectly when questioned about the particulars of EFT involving the administration of sustained-release medications (n = 152, 60.6%), soft gelatin capsules (n = 111, 44.4%) and hard gelatin capsules (n = 102, 40.6%). Meanwhile, in terms of practice, a majority of the nurses would correctly routinely flush the EFT before (n = 226, 90.4%) and after (n = 245, 98.8%) the administration of medications. However, only a small proportion of nurses (n = 43, 17.3%) demonstrated the appropriate practice of administering all medications separately all the time. Furthermore, it was also worth noting that for some specific knowledge-based questions, nurses from the intensive care setting had more correct responses when compared to those from the general ward setting (p < 0.05). Conclusion: The knowledge gap and inconsistencies in practices amongst nurses related to the use of EFT may lead to suboptimal delivery of medications, whilst potentially compromising patient outcomes. Hence, continuous educational programs should be carried out to ensure safe and effective drug administration through EFT.

Introduction

In the hospital setting, enteral feeding is a type of nutritional support for critically ill patients who are unable to tolerate oral feeding as a result of certain diseases or treatment modes. Enteral feeding plays an important role in providing adequate nutrition and preserving the function of the gastric mucosa in such patients. However, many factors must be considered when serving medications through enteral feeding tubes (EFT). Incorrect administration techniques may lead to several complications, including the clogging of EFT, reduced drug effectiveness and increased risk of adverse effects. Additionally, certain precautions should also be taken for certain drug formulations when given through the EFT, particularly, extended-release formulations and enteric-coated pills. Indeed, several cases have been reported whereby

improper administration of medications through EFT contributed to patient fatality and ineffective therapy [1][2].

Nurses are hugely responsible for the administration of medications for warded patients; hence they should be equipped with the knowledge and skills related to proper administration techniques with regards to EFT. Several studies have reported that nurses have insufficient knowledge related to this mode of administration, whilst also conducting numerous practices that diverge from standard guidelines [3][4]. including the administration of inappropriate dosage forms via EFT as well as the lack of tube flushing, where required. Inevitably, the lack of knowledge as well as the improper practices in administering medication through EFT may lead to complications, and eventually, compromised patient care.

To date, studies conducted locally to address this issue are few in number, while also being limited to West Malaysia. Indeed, the findings from those studies seem to indicate that there were discrepancies between nurses’ practice and standard guidelines on medication administration via EFT [3]. This study aims to provide an overview of nurses’ knowledge and practice on drug administration through EFT in Hospital Queen Elizabeth II (HQE2). This study also explores the preferred way by which nurses improve on their knowledge and practice relating to EFT. It is believed that the results of this research would prove to be beneficial in providing information towards the designing of future educational programs to improve the knowledge and practices of medication administration through EFT, with hopes of ultimately ensuring safer and more effective patient care.

Method

Study methods

This study was a cross-sectional study incorporating a self-administered questionnaire that involved ward-based nurses sampled by convenience sampling, with the experiment being conducted across the span of a few months from August to December 2020. It was conducted in Hospital Queen Elizabeth II, a 300-bedded tertiary centre that is capable of catering to both intensive and general ward patients. There is no sample size calculated as all the eligible nurses were invited to participate in this study. All ward-based nurses working in HQE2 were approached to participate in this study via text messages. The questionnaires were then distributed to all ward nurses respectively. Prior to answering the questionnaires, all participants gave their consent by signing the consent form. Subsequently, each ward would receive phone call reminders on the submission of completed questionnaires prior to the deadline given. The study was approved by the Medical Research and Ethics Committee with the identification code NMRR-20-2416-56357.

Instrument

The questionnaire was developed by the authors based on previous studies [3][4] and recommendations by the guidelines [5][6] on medication administration via EFT. With consideration of the skills and practice relating to the use of EFT, the questionnaire concisely included:

- 6 questions on socio-demographic information (age, gender, ward, highest education level, duration of service, frequency of dealing with EFT)

- 10 knowledge-based questions on the medications that can be administered through EFT and their specific administration method. The participants were given three options to choose from: “Yes”, “No”, and “I don’t know”.

- 9 practice-based questions on each stage of the medication administration using EFT and tube flushing. A four-point Likert scale was used to measure the frequency of such practices, ranging from “All the time” to “Never”.

- An open-ended question on the participants’ preferred way of improving their knowledge and practice relating to EFT

The questionnaire was appraised and subsequently content-validated by a team of pharmacists with expertise in survey design and clinical practice. Subsequently, a pre-test was conducted in July 2020 to undergo face-validation with five random ward nurses from different wards. Each of the pre-tested study participants was interviewed to obtain feedback on the comprehensibility, relevance and overall questionnaire. The feedback confirmed the face validity and user-friendliness of the questionnaire as no extra amendment was required. Since all the questions are being presented as individual responses, further validity and reliability tests were not carried out.

Data analysis

All the information collected was analysed using SPSS version 22.0. Continuous variables were presented as means (with standard deviation, SD) or medians (with interquartile range, IQR) depending on the normality of data distribution. Categorical data were presented as frequency and percentage. Descriptive analysis, i.e., number and percentages, was employed to describe nurses’ knowledge and practice on medication administration through EFT based on their responses. There is no score calculated for knowledge. The association between the nurses’ frequency of dealing with EFT, ward setting and their knowledge of EFT medication administration were tested using the Chi-square test. The responses for frequency of dealing with EFT were merged into 2 outputs: “All the time” and “Not all the time” (from “Often”,

“Sometimes” and “Never”) for ease of analysis. The association between the median duration of service and knowledge was also explored using the Mann-Whitney U test. A p-value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Demographic

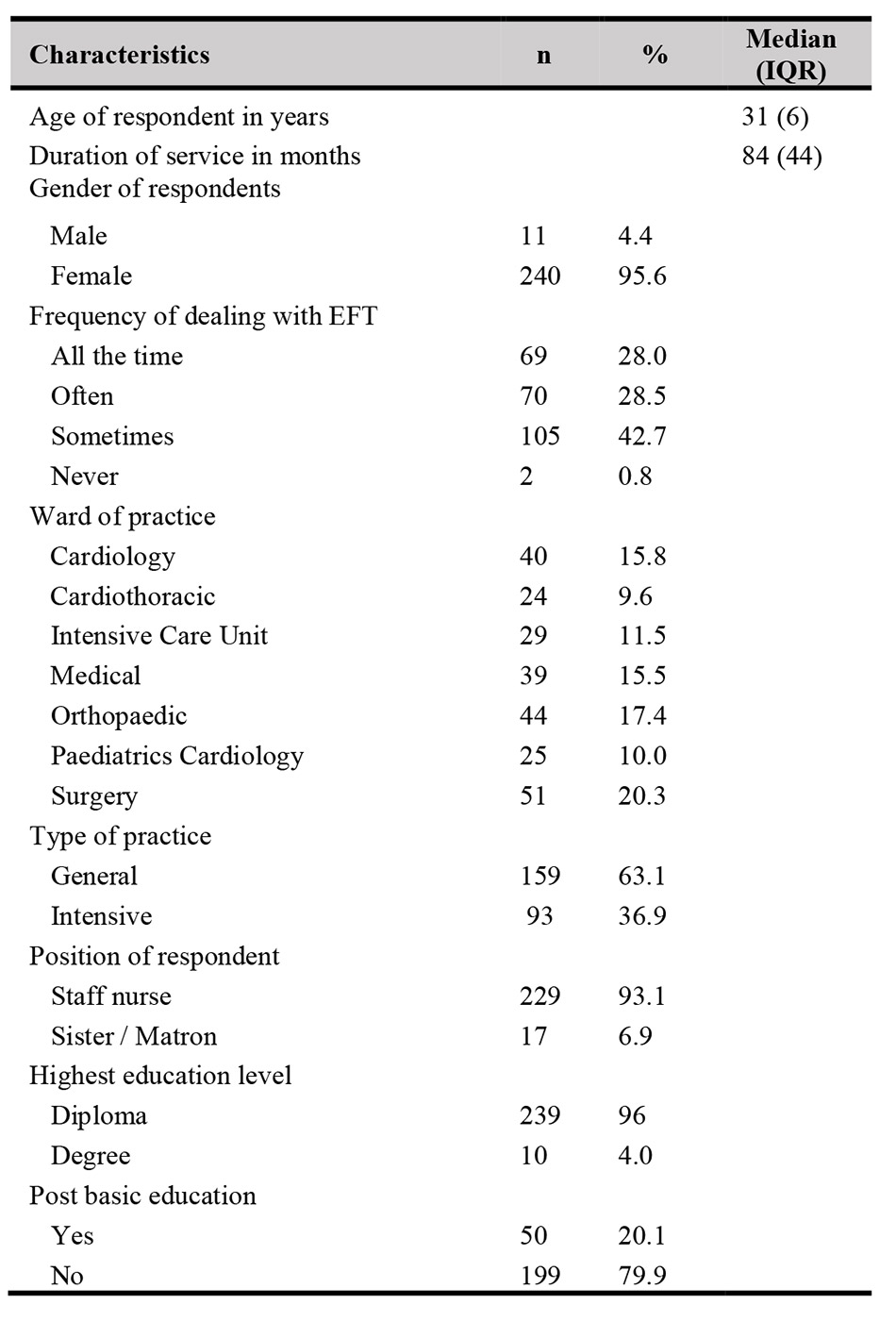

A total of 252 ward nurses participated in this study, which accounted for an estimated response rate of 61%. The demographic data of all respondents are presented in Table I. The median age of participating ward nurses was 31 years (IQR = 6), whereas the median duration of service was 84 months (IQR = 44). The majority of the participants were female (95.6%) and positioned as staff nurses (93.1%). Most of the ward nurses (99.2%) had experience in conducting medication administration via EFT, of which 28% claimed that they dealt with it all the time.

Knowledge on medication administration through EFT

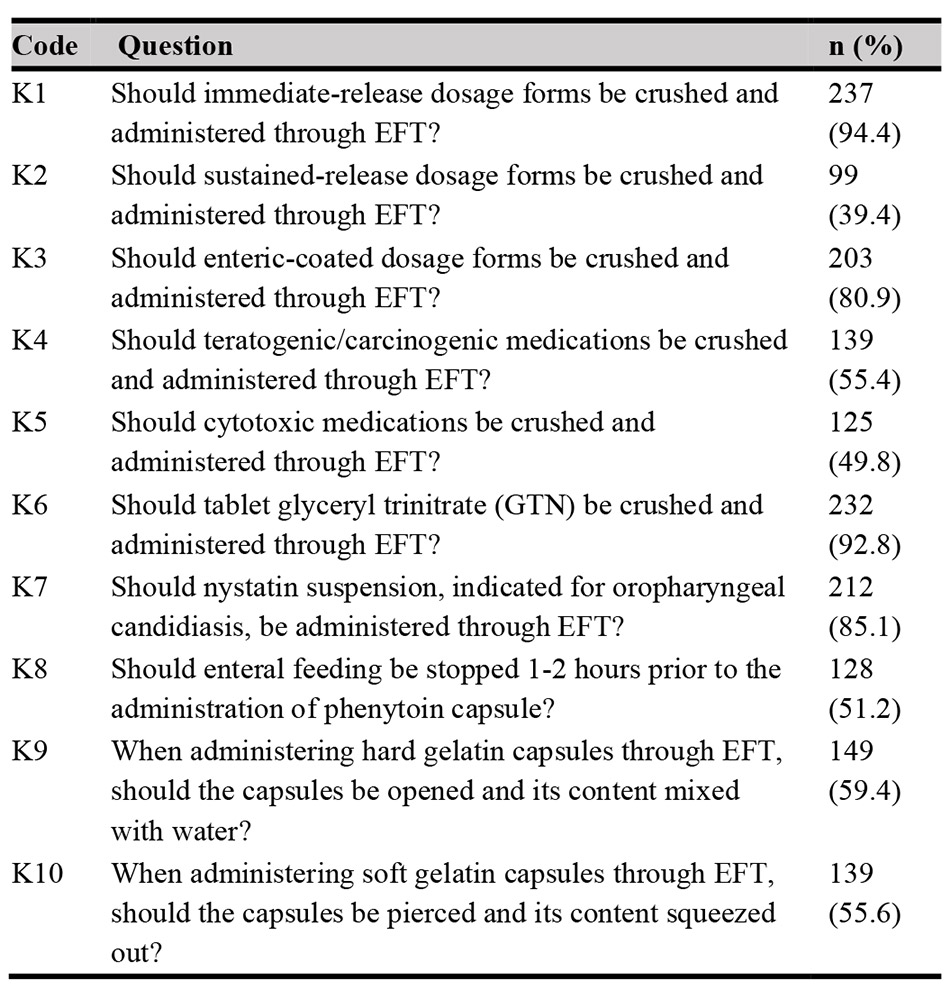

The proportion of nurses that answered correctly in the knowledge-based questions are shown in Table II. In terms of the administration through EFT, knowledge related to the proper administration of immediate-release dosage forms and GTN tablets were known best by the nurses, with 94.4% and 92.8% correct responses respectively. In contrast, knowledge related to the proper administration of the following two types of medication; sustained-release formulations and cytotoxic medications, were found to be the lowest with 39.4% and 49.8% of nurses answering with correct responses respectively.

Practice of medications administration via EFT

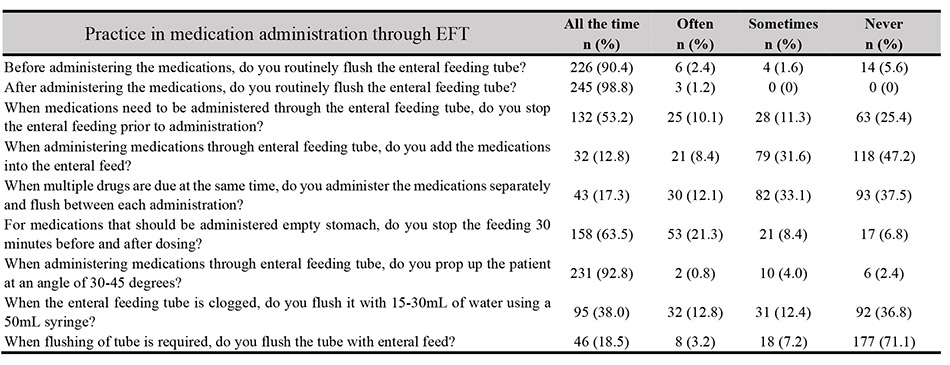

The data gathered pertaining to the practice of medication administration via EFT are shown in Table III. Most of the nurses claimed that they flush the EFT routinely before (90.4%) and after (98.8%) medication administration. The majority of nurses (92.8%) also claimed to prop up their patients all the time when administering medications to patients via EFT. However, only a small proportion of nurses (17.3%) responded that they, appropriately, administer different medications separately and flush between each administration all the time. Additionally, only half of the nurses (53.2%) would stop enteral feeding when it is time to administer medications via EFT.

Association of demographic and knowledge

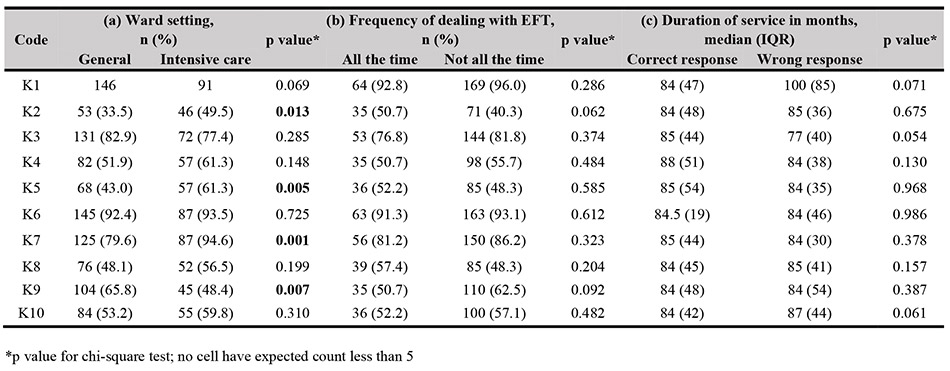

Our study revealed that nurses from the intensive care setting had more correct responses to particular knowledge-based questions as compared to those from the general ward setting (p < 0.05) as shown in Table IV. Such a finding may not be unexpected on account of the fact that a higher proportion of nurses in the intensive care setting reportedly deal with patients requiring EFT all the time (42.9%) as compared to those in the general setting (19.4%). Nevertheless, the duration of services and frequency of handling EFT did not seem to be significantly associated with their level of knowledge (refer Table IV).

Preferred way of improving their knowledge and practice relating to EFT

Most of the nurses stated that their most preferred way of improving EFT techniques was through online educational programs, followed by reading materials and bedside teaching.

Discussion

Overall, the sample of nurses in this study demonstrated a good understanding of proper EFT administration of commonly encountered medications. However, our findings also identified instances of lack of compliance in their knowledge and practice compared to current guidelines. Notably, there was a lack of awareness in two facets; the fact that sustained-release/modified-release formulations should not be crushed, and the unfamiliarity with the proper administration method of teratogenic/carcinogenic medications, and indeed, similar findings are reported in previous studies [3][4]. Incognizance of the former can be alarming because adverse events and fatality due to crushed sustained-release medications have previously been reported [1][2]. In theory, crushing such formulations may affect the pharmacokinetic profile of the drug, resulting in excessive peak plasma concentrations and side effects [5]. Meanwhile, the correct administration method of teratogenic/carcinogenic medications should be reinforced so as to avoid the exposure of nurses themselves to the teratogenic effects of the medications. [6]. It is highly encouraged for nurses to be familiar with the types of medications for which feeding needs to be stopped for 1-2 hours prior to administration to avoid potential drug-feeding interactions. [7].

In terms of practice, most nurses in this study were also reported to have demonstrated good practice when it comes to the routine flushing of EFT before and after medication administration. Despite that, in situations where multiple different medications are to be administered, only a few nurses would flush between medications and administer them separately all the time. These findings are congruent with a previous study conducted in Malaysia [3], whereby more than half of the nurses reportedly add the medications into the enteral formula during administration, while unfortunately administering multiple drugs at the same time. A small number of nurses even claimed that they would flush the EFT with enteral formula. Such practices are highly discouraged by current guidelines due to the risks of drug-nutrient and drug-drug interactions. [6]. Although adverse events were rarely reported due to administering multiple medications concurrently through EFT, it cannot be denied that drug-drug interactions and disruption in drug absorption may occur, leading to either adverse effects or poor treatment outcomes [8]. Meanwhile, drug-nutrient interactions could potentially contribute to tube clogging, hindering the delivery of medications and ultimately leading to suboptimal treatment [9][10]. Flushing of EFT with enteral formula also provides a favourable environment for bacterial growth that may increase the risk of infection [9][10]. Hence, good practice in EFT medication administration is crucial in maintaining the patency and hygiene of the EFT for its safe and effective use.

Nurses in the intensive care practice have a higher tendency to know that sustained-release formulations, cytotoxic medications and Nystatin suspension should not be crushed or served through EFT. This is possibly due to a more frequent exposure to the handling of EFT in the intensive care setting; a higher number of nurses in the intensive care practice reported that they handle EFT all the time compared to those in general care. [3][4].

In our study, the most preferred way of improving EFT techniques by nurses would be through online educational programs, possibly due to the convenience it offers, which can especially be true during the pandemic period. On the other hand, previous studies have demonstrated that education programs given through evidence-based booklets and teaching sessions have been successful in improving nurses’ knowledge and practice [11][12][13][14][15]. Specifically, a study by Chen CJ et. al. reported that after an educational program was carried out, the ordinary drug delivery error rate fell significantly from 60.83% to 2.42% [11].

The main limitation of this research is that it was a single-centre study. Another limitation is that the assessment of nurses’ practice was solely based on a questionnaire, rather than by direct observation. Our suggestion for future studies would be to incorporate direct observation as part of the assessment, besides also including an intervention such as the education on EFT medication administration.

Conclusion

The knowledge gaps and inconsistencies in practices may affect the delivery of medications through enteral feeding, and may potentially compromise patient outcomes. Hence, continuous educational programs should be carried out to ensure that the practice of nurses related to enteral feeding is safe, effective and up to date.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the Director-General of Health Malaysia for his permission to publish this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. This case report did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Reference

- Cornish P. “Avoid the crush”: hazards of medication administration in patients with dysphagia or a feeding tube. CMaj. 2005; 172 (7): 871-872. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.050176

- Schier JG, Howland MA, Hoffman RS, Nelson LS. Fatality from administration of labetalol and crushed extended-release nifedipine. Ann Pharmacother. 2003 Oct;37(10):1420-3. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.050176

- Oh PY, Lai WM, Hoo FK, Boo YL, Ramachandran V, Ching SW.Techniques of medications administration through enteral feeding catheters in a tertiary care hospital, Malaysia. Rawal Med J. 2016; 41:225-229.https://www.rmj.org.pk/?mno=208060

- Phillips NM, Endacott R. Medication administration via enteral tubes: a survey of nurses’ practices. J Adv Nurs. 2011 Dec;67(12):2586-92. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05688.x

- Critical Care Pharmacy Handbook 2013. Malaysia: Pharmaceutical Division, Ministry of Health Malaysia. 1st edition. 2013. https://www.pharmacy.gov.my/v2/sites/default/files/document-upload/critical-care-handbook-2013.pdf

- White R, Bradnam V. Handbook of Drug Administration via Enteral Feeding Tubes. 3rd edition. 2015.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/312496705_Handbook_of_Drug_Administration_via_Enteral_Feeding_Tubes_3rd_Ed

- Au Yeung SC, Ensom MH. Phenytoin and enteral feedings: does evidence support an interaction? Ann Pharmacother. 2000 JulAug;34(7-8):896-905. https://doi.org/10.1345/aph.19355

- Ferreira Silva R, Rita Carvalho Garbi Novaes M. Interactions between drugs and drug-nutrient in enteral nutrition: a review based on evidences. Nutr Hosp. 2014 Sep 1;30(3):514-8. https://doi.org/10.3305/nh.2014.30.3.7488

- Best C. Enteral tube feeding and infection control: how safe is our practice? Br J Nurs. 2008 Sep 11-24;17(16):1036, 1038-41. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2008.17.16.31069

- Malhi H. Enteral tube feeding: using good practice to prevent infection. Br J Nurs. 2017 Jan 12;26(1):8-14. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2017.26.1.8

- Chen CJ, Lee HF, Fang YC, et al. Improving Nurse Skill of Medication Administration via Enteral Feeding Tube. Nur Primary Care. 2018; 2(5): 1-5. https://doi.org/10.33425/2639-9474.1078

- Dashti-Khavidaki S, Badri S, Eftekharzadeh SZ, Keshtkar A, Khalili H. The role of clinical pharmacist to improve medication administration through enteral feeding tubes by nurses. Int J Clin Pharm. 2012 Oct;34(5):757-64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-012-9673-8

- Hossaini Alhashemi S, Ghorbani R, Vazin A. Improving knowledge, attitudes, and practice of nurses in medication administration through enteral feeding tubes by clinical pharmacists: a case-control study. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2019; 10: 493-500. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S203680

- Abu Hdaib N, Albsoul-Younes A, Wazaify M. Oral medications administration through enteral feeding tube: Clinical pharmacist-led educational intervention to improve knowledge of Intensive care units’ nurses at Jordan University Hospital. Saudi Pharm J. 2021;29(2):134- 142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2020.12.015

- Dashti-Khavidaki S, Badri S, Eftekharzadeh SZ, Keshtkar A, Khalili H. The role of clinical pharmacist to improve medication administration through enteral feeding tubes by nurses. Int J Clin Pharm. 2012 Oct;34(5):757-64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-012-9673-8

Please cite this article as:

Laura Soon, Pay Chyi Tong, Le Jun Chung, Sze Ling Tan and Qing Liang Goh, Medication Administration via Enteral Feeding Tubes: A Survey of Nurses’ Knowledge and Practice. Malaysian Journal of Pharmacy (MJP). 2022;1(8):26-31. https://mjpharm.org/medication-administration-via-enteral-feeding-tubes-a-survey-of-nurses-knowledge-and-practice/