ABSTRACT

Introduction: The COVID-19 Antigen Rapid Test Kit (self-test) has been a critical tool in Malaysia’s public health response, approved by the Ministry of Health (MOH) for detecting COVID-19 antigens using saliva or nasal swabs. This study evaluates the public’s willingness to pay (WTP) for these self-test kits and identifies the factors influencing this willingness. Method: A cross-sectional, web-based survey was conducted among members of the public in Malaysia from March to December 2022. The self-administered questionnaire assessed respondents’ exposure to COVID-19, vaccination status, awareness of self-test kits, and WTP. The contingent valuation method was applied, with price points ranging from RM 3.00 to RM 20.00. Results: Among the 268 respondents, 96.6% had previously purchased a COVID-19 self-test kit, and 91.0% were aware of both nasal and saliva-based kits. A majority (73.5%) expressed a willingness to pay for these kits, with a mean maximum price of RM 9.16 and a median of RM 6.00. Significant predictors of higher WTP included female gender (P = 0.013) and student status (P = 0.013). The primary reasons for refusal to pay were cost and affordability (62.7%). Conclusion: This study demonstrates a strong willingness among the Malaysian public to pay for COVID-19 self-test kits. These findings provide critical insights for policymakers and health authorities in setting prices and considering subsidies to enhance public health preparedness for future pandemics.

INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by a newly discovered coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV2), which was initially discovered in Wuhan, China, in December 2019 [1]. Data from 2019 has estimated about 5.09 million people died from COVID-19 worldwide, with Malaysia contributing 1.71% of all deaths [2]. According to the most recent data records from the KKMNOW (Ministry of Health’s One-stop Centre for Malaysia’s Health Data) website on 22nd April 2024, Malaysia has recorded a total of 37,349 deaths [3].

One of the important public health measures against COVID-19 advocated by the World Health Organisation (WHO) is to ensure the availability of COVID-19 Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDT) in the community [4]. In accordance with Malaysia’s, Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases Act 1988 (Act 342), testing plays a crucial role in the early identification of cases and close contacts to manage the cases and implement preventative and control measures. The COVID-19 Antigen Rapid Test Kit (self-test) is an RDT device approved by Ministry of Health Malaysia (MOH) and Medical Device Authority (MDA) for the detection of antigens causing COVID-19 by using saliva or nasal swab.

Rapid test-kit antigen (RTK-Ag) detects SARS-CoV-2 viral proteins directly and offers the advantage of providing fast results, being affordable, and being suitable for point-of-care testing [5]. It has been used in Malaysia since May 6, 2020, as an alternative to reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing, providing results in a shorter period and offering services when RT-PCR testing is not readily available. The RDT kits are widely available and can be purchased at community pharmacies and private health facilities, or supplied by MOH facilities as required [6].

In a bid to encourage regular self-testing, the government has gradually reduced the prices of the RTD kits to increase their affordability for the public. Despite their widespread availability and the potential to change the scenario of COVID-19 diagnosis and management, in-depth explorations of the public’s willingness to pay for the COVID-19 RDT kits are still important to guide price setting, price differentiation, price subsidization, and other program design features that enhance affordability, equity, and uptake.

This study was designed to assess the extent of willingness to pay, awareness, and perceptions among the public on the COVID-19 self-test kits, as well as to examine the level and determinants behind their willingness of pay for the self-testing kits.

METHOD

This was a cross-sectional descriptive survey involving the public, conducted from March to December 2022. Malaysian citizens aged 18 years old and above, without cognitive disabilities who understand Malay and English language were included. Those refused to provide consent excluded from the study. To determine the sample size, as there was no consensus on the optimal sample size for Willingness-To-Pay (WTP) studies [7], a minimum target of 250 responses was set.

The data collection tool comprised of sections on history of exposure to COVID-19 infection (1 question), COVID-19 vaccination status (3 questions), awareness of the COVID-19 self-test kits (3 questions), attitude towards COVID-19 self-test kits (1 question), willingness to pay for the COVID-19 test kits (14 questions), and demographic data of the respondents (7 questions). The questions were developed in consultation with senior pharmacists, with specific WTP questions on WTP modelled after a similar study conducted in Kenya [8].

Questions regarding COVID-19 vaccination status included the number of doses received and their types. The awareness section assessed knowledge about the existence of COVID-19 self-test kits, types available and whether respondents had purchased COVID-19 test kits prior to the study. The attitude sectionincluded 10 multiple-choice questions with “Yes” or “No” options, asking respondents about their willingness to conduct COVID-19 self-tests under various scenarios, such as before and after interstate or international travel, before attending courses or meetings, or when symptomatic or a close contact of a confirmed case.

The assessment of WTP was divided into two main aspects. First, we evaluated perspectives on who should cover the costs of COVID-19 self-test kits – either individuals, employers, the government, or healthcare insurance providers- either partially or in fully. Respondents were also asked if they were willing to pay for their own COVID-19 self-test kits before evaluating their willingness to pay at different prices. A dichotomous-choice (Yes or No) contingent valuation method was applied to gauge WTP at prices, ranging from RM 3.00 to RM 20.00 per set of COVID-19 test kit, with increments of RM 2.00 to RM 3.00 price between each bid. Additionally, respondents indicated the maximum price they were willing to pay for a COVID-19 self-test kit. If the respondents were not willing to pay for a COVID-19 self-test kit, they were required to inform the underlying reasons.

Demographic data collected in included ethnicity, age, gender, current state of residence, location category of residence (urban, suburban or rural), highest education level (primary, secondary, college/university or no formal education), occupation (government, private/self-employment, student, retiree or unemployed), living status (alone, with family or with non-family members), and monthly household income.

The pilot study revealed redundancy in two questions, which were combined: “No history of COVID-19 contact whatsoever” and “History of being a person under investigation (PUI) or person under surveillance (PUS)”. The finalised questionnaire was produced electronically via Google Forms, and disseminated through social media platforms, namely Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and WhatsApp messenger, to promote public participation.

IBM SPSS Statistics Version 20.0 was used to analyse the study findings. Descriptive statistics were used to describe demographic data of the respondents, including the use of Chi-Square or Fischer-Exact Tests for categorical data comparison. Numerical data, presented as means with standard deviations were analysed via T-Test or Mann-Whitney Tests. Pearson’s and Spearman’s Correlation Co-efficient tests were used to evaluate the association between different variables.

This study was registered with the National Medical Research Register (NMRR ID-22-00132-GWX). Ethical approval was obtained from the Medical Research Ethics Committee (MREC) in the Ministry of Health Malaysia before commencement of the study.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics

A total of 280 responses were initially received from the survey. However, upon further screening, 12 respondents did not fulfil the inclusion criteria of the study, including nationality and age limits, and was hence excluded from our analysis. This resulted in a final total of 268 respondents (no duplicate or missing data were found among the finalised sample). The demographic

Table Ⅰ. Demographic Characteristics (n=268)

| Demographic Characteristic | Demographic Characteristic | n (%) |

| Age group | 18-25 | 57 (21.3) |

| 26-35 | 60 (22.4) | |

| 36-45 | 71 (26.5) | |

| 46-55 | 70 (26.1) | |

| 56-65 | 8 (3.0) | |

| 65 and above | 2 (0.7) | |

| Gender | Male | 66 (24.6) |

| Female | 202 (75.4) | |

| Race | Malay | 237 (88.4) |

| Chinese | 20 (7.5) | |

| Indian | 9 (3.4) | |

| Minangkabau | 1 (0.4) | |

| Suluk | 1 (0.4) | |

| Current State of | ||

| Residence | Kedah | 124 (46.3) |

| Selangor | 32 (11.9) | |

| Perak | 28 (10.4) | |

| Wilayah Persekutuan Kuala Lumpur | 17 (6.3) | |

| Pahang | 14 (5.2) | |

| Pulau Pinang | 12 (4.5) | |

| Johor | 11 (4.1) | |

| Kelantan | 11 (4.1) | |

| Terengganu | 6 (2.2) | |

| Negeri Sembilan | 4 (1.5) | |

| Sabah | 4 (1.5) | |

| Melaka | 2 (0.7) | |

| Sarawak | 2 (0.7) | |

| Wilayah Persekutuan Labuan | 1 (0.4) | |

| Location of Residence | Urban | 149 (55.6) |

| Suburban | 60 (22.4) | |

| Rural | 59 (22.0) | |

| Education Level | College/University | 236 (88.1) |

| Secondary School | 31 (11.6) | |

| No Formal Education | 1 (0.4) | |

| Occupation | Government | 139 (51.9) |

| Private/Self | 78 (29.1) | |

| Employment | Retired | 8 (3.0) |

| Student | 23 (8.6) | |

| Unemployed | 20 (7.5) | |

| Living Status | Alone | 26 (9.7) |

| With Family | 225 (84.0) | |

| With Non-Family | 17 (6.3) | |

| Monthly Household Income | Less than RM1,000 | 10 (3.7) |

| RM1,001-RM2,000 | 28 (10.4) | |

| RM2,001-RM3,000 | 34 (12.7) | |

| RM3,001-RM4,000 | 46 (17.2) | |

| RM4,001-RM5,000 | 29 (10.8) | |

| More than RM5,000 | 121 (45.1) |

characteristics of the respondents are illustrated in Table Ⅰ. The majority of the respondents were female (n=202, 75.4%), aged between 36-45 years (n=71, 26.5%), Malay (n = 237, 88.4%), residing in Kedah state (n=124. 46.3%), living in urban area (n=149, 55.6%), having completed tertiary education (n=236, 88.1%), working in the government sector (n=139, 51.9%), living with family members (n=225, 84.0%), and with a monthly household income of more than RM5000 (n=121, 45.1%).

Exposure to COVID-19 infection

The responses regarding our respondents’ history of exposure to COVID-19 infection are illustrated in Table Ⅱ. The majority of our respondents had not been infected by COVID-19 (n=152, 56.7%) nor classified as a Person under Investigation (PUI) or Person Under Surveillance (PUS) (n=144, 53.7%). A vast majority had also not been hospitalised or admitted to COVID-19 Treatment and Quarantine Centres (PKRC) due to COVID-19 infection (n=269, 97.0%), and reported no history of death among family members (n=221, 82.5%) or acquaintances (n=185, 69.0%) due to COVID-19 infection. Nevertheless, the majority of them had family members (n=207, 77.2%) or close acquaintances (n=257, 95.9%), who were infected by COVID-19, experienced COVID-19 cases in their neighbourhood (n=244, 91.0%) or at their workplace (n=226, 84.3%), and with experience of being tested for COVID-19 infection via RTK-Ag or PCR testing (n=227, 84.7%).

COVID-19 vaccination status

The details of respondents’ COVID-19 vaccination status are illustrated in Table Ⅲ. A vast majority of our respondents received at least 2 doses of COVID-19 vaccines (n=267, 99.6%), primarily the Pfizer Comirnaty Vaccine (n=186, 69.4%).

Table Ⅲ. Vaccination status (n=268)

| Question | Frequency, n | Percentage (%) |

| Vaccination status | ||

| Partially vaccinated | 1 | 0.4 |

| Fully vaccinated | 46 | 17.2 |

| Received booster dose | 221 | 82.5 |

| Types of vaccine received | ||

| Pfizer | 186 | 69.4 |

| Sinovac | 47 | 17.5 |

| Astra Zeneca | 27 | 10.1 |

| Johnson & Johnson | 1 | 0.4 |

| Mix | 7 | 2.6 |

Table Ⅱ. Exposure to COVID-19 infection

| Questions | Frequency | P-Value | |

| Yes | No | ||

| History of being infected by COVID-19 | 116 (43.3) | 152 (56.7) | 0.028 |

| History of being a person under investigation (PUI) or person under surveillance (PUS) | 124 (46.3) | 144 (53.7) | 0.222 |

| History of hospitalizations or admission to PKRC due to infected with COVID-19 | 8 (3.0) | 260 (97.0) | <0.001 |

| History of family member being infected by COVID-19 | 207 (77.2) | 61 (22.8) | <0.001 |

| History of a close acquaintance being infected by COVID-19 | 257 (95.9) | 11 (4.1) | <0.001 |

| History of death among family members due to COVID-19 | 47 (17.5) | 221 (82.5) | <0.001 |

| History of death among close acquaintance due to COVID-19 | 83 (31.0) | 185 (69.0) | <0.001 |

| History of COVID-19 case around neighbourhood area | 244 (91.0) | 24 (9.0) | <0.001 |

| History of COVID-19 case at workplace area | 226 (84.3) | 42 (15.7) | <0.001 |

| History of RTK-Ag/PCR test | 227 (84.7) | 41 (15.3) | <0.001 |

Experience of purchasing & awareness of the existence of COVID-19 self-test kit

The responses regarding awareness of COVID-19 self-test kits are illustrated in Table Ⅳ. All respondents were aware of the existence of COVID-19 self-test kits (n=268, 100%), and the majority (n=259, 96.6%) had purchased them before. Most respondents (n=252, 91.0%) were able to identify the types of COVID-19 self-test kit available in the market, which include nasal and saliva specimens.

Table Ⅳ. Awareness of the existence of COVID-19 self-test kit (n=268)

| Question | Frequency, n | Percentage (%) |

| Did you know about the existence of COVID-19 self-test kit? | ||

| Yes | 268 | 100.0 |

| Did you know the type of COVID-19 self-test kit? | ||

| Nasal specimen | 2 | 0.7 |

| Saliva specimen | 22 | 8.2 |

| Both | 244 | 91.0 |

Table Ⅴ. Willingness to pay for the COVID-19 Self-Test Kit (n=268)

| Willingness to pay | Yes | No | |

| Willingness to pay for the COVID-19 Self-Test Kit | 197 (73.5) | 71 (26.5) | |

| Willingness to pay | No | Yes, pay partially | Yes, pay fully |

| Individuals have to spend their own money to pay for the COVID-19 self-test kit | 69 (25.7) | 97 (36.2) | 102 (38.1) |

| Employer has to pay for the COVID-19 Self-Test Kit | 41 (15.3) | 80 (29.9) | 147 (54.9) |

| Government has to pay for the COVID-19 self-test kit | 41 (15.3) | 99 (36.9) | 128 (47.8) |

| Health insurance has to pay for the COVID-19 self-test | 44 (15.3) | 59 (22.0) | 168 (62.7) |

Willingness to pay for the COVID-19 self-test kit

The details on respondents’ willingness-to-pay for COVID-19 self-test kits are illustrated in Table Ⅴ. The majority of our respondents were willing to pay for the COVID-19 self-test kits (n=197, 73.5%). 74.3% (n=199) of the respondents agreed that individuals should spend their own money to pay for the COVID-19 self-test kits, either partially or fully. However, they also perceived that the employers (n=227, 84.7%), the government (n=227, 84.7%), and the health insurance providers (n=227, 84.7%) should also partially of fully fund the COVID-19 self-test kits.

Table Ⅵ illustrats the reasons why some respondents refused to pay for the COVID-19 self-test kits. Out of 71 respondents who disagreed to pay for COVID-19 Self-test kits, 70 of them provided their reasons (n=80), which included cost and affordability issues (n=52, 65.0%), the number of family members to subsidise (n=11, 13.8%), and the need to test frequently (n=10, 12.5%), as summarized in Table VI.

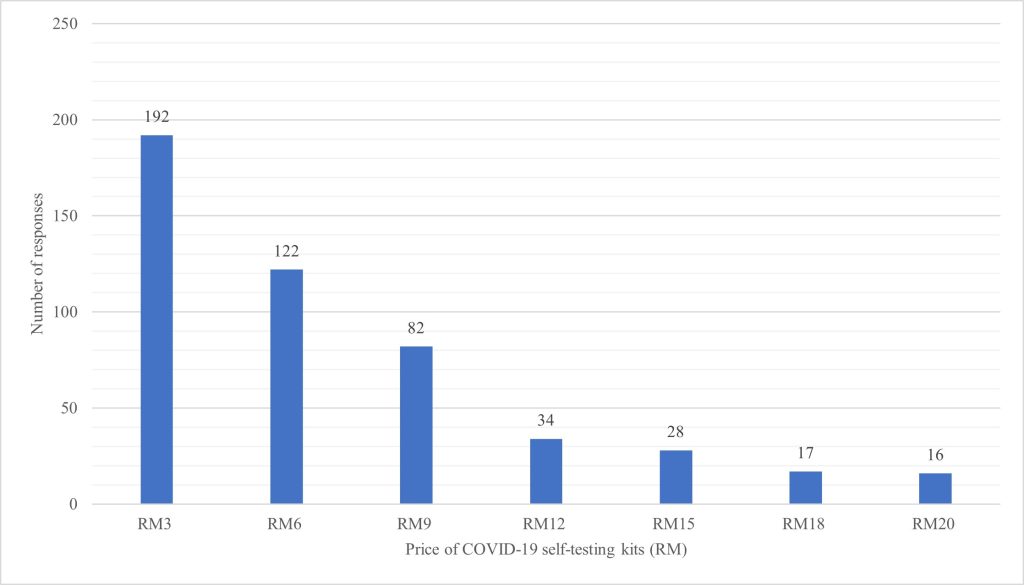

The extent of willingness-to-pay for COVID-19 self-test kits based on price differences is further illustrated in Figure Ⅰ. Among the 198 respondents who answered this section, the majority of them were comfortable spending RM 3.00 to RM 6.00 for a set of COVID-19 self-test kit, with a mean maximum price of RM 9.16 (SE = 0.68) and a median maximum price of RM 6.00.

Table Ⅵ. Reasons of refuse to pay for COVID-19 self-test kit

(No. of respondent answered = 70, no. of responses = 83)

| Reason of unwillingness to pay | Frequency | Percent |

| Cost & affordability | 52 | 62.7 |

| The need to test frequently | 10 | 12.0 |

| The number of family members to subsidise | 11 | 13.3 |

| Unnecessary | 7 | 8.4 |

| The cost should be borne by the government and authorities | 3 | 3.6 |

Attitude towards COVID-19 self-tests

Perspectives on attitudes towards performing COVID-19 self-tests under various situations are illustrated in Table Ⅶ (n=268). The majority of our respondents possessed a positive attitude towards COVID-19 self-tests; they were willing to take tests before interstate travel for work (n=221, 82.5%) or personal matters (n=214, 79.9%), before international travelling for work (n=228, 85.1%) or personal matters (n=225, 84.0%), after returning from interstate travel, and before starting work (n=231, 86.2%). They were also willing to perform COVID-19 self-tests prior to attending meetings or trainings sessions involving more than 30 participants (n=203, 75.7%), and importantly, when they are symptomatic (n=257, 95.9%) or when they became a closed contact (n=253, 94.4%).

Table Ⅶ. Attitude towards COVID-19 Self-Test Kit (n=268)

| Question | Frequency | Percentage | ||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Are you willing to take COVID-19 self-test for all of the followings: | ||||

| Before doing cross-state activities on work matters | 221 | 47 | 82.5 | 17.5 |

| Before doing cross-state activities on personal matters | 214 | 54 | 79.9 | 20.1 |

| Before doing cross-country activities on work matters | 228 | 40 | 85.1 | 14.9 |

| Before doing cross-country activities on personal matters | 225 | 43 | 84.0 | 16.0 |

| After returning from cross-state activities and before starting work | 231 | 37 | 86.2 | 13.8 |

| Before attending a meeting or training involving more than 30 participants | 203 | 65 | 75.7 | 24.3 |

| Before attending meetings or trainings involving participants from various districts or states | 211 | 57 | 78.7 | 21.3 |

| If symptomatic | 257 | 11 | 95.9 | 4.1 |

| If becoming a closed contact | 253 | 15 | 94.4 | 5.6 |

Table Ⅷ. Factors associated with willingness to pay for COVID-19 self-test kit (n=268)

| Demographic Characteristic | n (%) | Willingness to pay, n (%) | p-valuea | |

| Yes | No | |||

| Age | 0.300a | |||

| 18-25 | 57 (21.3) | 45 (78.9) | 12 (21.1) | |

| 26-35 | 60 (22.4) | 47 (78.3) | 13 (21.7) | |

| 36-45 | 71 (26.5) | 45 (63.4) | 26 (36.6) | |

| 46-55 | 70 (26.1) | 52 (74.3) | 18 (25.7) | |

| 56-65 | 8 (3.0) | 6 (75.0) | 2 (25.0) | |

| 65 and above | 2 (0.7) | 2 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Gender | 0.013b | |||

| Male | 66 (24.6) | 41 (62.1) | 25 (37.9) | |

| Female | 202 (75.4) | 156 (77.2) | 46 (22.7) | |

| Race | 0.073a | |||

| Malay | 237 (88.4) | 173 (73.0) | 64 (27.0) | |

| Chinese | 20 (7.5) | 18 (90.0) | 2 (10.0) | |

| Indian | 9 (3.4) | 5 (55.5) | 4 (44.4) | |

| Minangkabau | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | |

| Suluk | 1 (0.4) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| State of Residence | 0.386a | |||

| Kedah | 124 (46.3) | 86 (69.4) | 38 (30.6) | |

| Selangor | 32 (11.9) | 27 (84.4) | 5 (15.6) | |

| Perak | 28 (10.4) | 23 (82.1) | 5 (17.8) | |

| Wilayah Persekutuan Kuala Lumpur | 17 (6.3) | 11 (64.7) | 6 (35.3) | |

| Pahang | 14 (5.2) | 9 (64.3) | 5 (35.7) | |

| Pulau Pinang | 12 (4.5) | 10 (83.3) | 2 (16.6) | |

| Johor | 11 (4.1) | 6 (54.5) | 5 (45.5) | |

| Kelantan | 11 (4.1) | 8 (72.7) | 3 (27.3) | |

| Terengganu | 6 (2.2) | 5 (83.3) | 1 (16.7) | |

| Negeri Sembilan | 4 (1.5) | 4 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Sabah | 4 (1.5) | 4 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Melaka | 2 (0.7) | 2 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Sarawak | 2 (0.7) | 2 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Wilayah Persekutuan Labuan | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | |

| Location of Residence | 0.491a | |||

| Urban | 149 (55.6) | 107 (71.8) | 42 (28.2) | |

| Suburban | 60 (22.4) | 43 (71.7) | 17 (28.3) | |

| Rural | 59 (22.0) | 47 (79.7) | 12 (20.3) | |

| Education Level | 0.470a | |||

| College/University | 236 (88.1) | 176 (74.6) | 60 (25.4) | |

| Secondary School | 31 (11.6) | 20 (64.5) | 11 (35.5) | |

| No Formal Education | 1 (0.4) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Occupation | 0.013a | |||

| Government | 139 (51.9) | 104 (74.8) | 35 (25.2) | |

| Private/Self Employment | 78 (29.1) | 58 (74.4) | 20 (25.6) | |

| Retired | 8 (3.0) | 5 (62.5) | 3 (37.5) | |

| Student | 23 (8.6) | 21 (91.3) | 2 (8.7) | |

| Unemployed | 20 (7.5) | 9 (45.0) | 11 (55.0) | |

| Living Status | 0.236a | |||

| Alone | 26 (9.7) | 17 (65.4) | 9 (34.6) | |

| With Family | 225 (84.0) | 165 (73.3) | 60 (26.7) | |

| With non-family | 17 (6.3) | 15 (88.2) | 2 (11.8) | |

| Monthly Household Income | 0.071a | |||

| Less than RM1,000 | 10 (3.7) | 5 (50.0) | 5 (50.0) | |

| RM1,001-RM2,000 | 28 (10.4) | 21 (75.0) | 7 (25.0) | |

| RM2,001-RM3,000 | 34 (12.7) | 19 (55.9) | 15 (44.1) | |

| RM3,001-RM4,000 | 46 (17.2) | 35 (76.1) | 11 (31.4) | |

| RM4,001-RM5,000 | 29 (10.8) | 22 (75.9) | 7 (24.1) | |

| > RM5,000 | 121 (45.1) | 95 (78.5) | 26 (21.5) | |

aChi-Square Test; * P < 0.05 bFisher Exact Test; * P < 0.05

The level and determinants of the willingness of public to pay for the COVID-19 self-test kit

Table Ⅷ illustrates the factors associated with respondents’ willingness to pay for COVID-19 self-test kits. It was found that female gender (P=0.013) and students (P=0.013) were associated with higher odds of willingness to pay for COVID-19 self-test kits.

Table Ⅸfurther illustrates the correlation between respondents’ exposure to COVID-19 infection and their WTP for COVID-19 self-test kits. It was found that having close acquaintances infected with COVID-19 was significantly associated (P = 0.009) with willingness-to-pay for COVID-19 self-test kits.

Table Ⅸ. Correlation between exposure to COVID-19 infection and Willingness-To-Pay (WTP) for COVID-19 self-test kit (n=268)

| Items | n (%) | Willingness to pay, n (%) | p-valuea | |

| Yes | No | |||

| History of being infected by COVID-19 | 0.838 | |||

| Yes | 116 | 86 | 30 | |

| No | 152 | 111 | 41 | |

| History of hospitsalisation due to COVID-19 infection | 1.000 | |||

| Yes | 8 | 6 | 2 | |

| No | 260 | 191 | 69 | |

| History of family member being infected by COVID-19 | 0.869 | |||

| Yes | 207 | 153 | 54 | |

| No | 61 | 44 | 17 | |

| History of close acquaintance being infected by COVID-19 | 0.009 | |||

| Yes | 257 | 193 | 64 | |

| No | 11 | 4 | 7 | |

| History of death among family members due to COVID-19 | 0.467 | |||

| Yes | 47 | 37 | 10 | |

| No | 221 | 160 | 61 | |

| History of death among close acquaintance due to COVID-19 | 0.178 | |||

| Yes | 83 | 66 | 17 | |

| No | 185 | 131 | 54 | |

| History of COVID-19 case around neighbourhood area | 0.227 | |||

| Yes | 244 | 182 | 62 | |

| No | 24 | 15 | 9 | |

| History of COVID-19 case at workplace area | 0.568 | |||

| Yes | 226 | 168 | 58 | |

| No | 42 | 29 | 13 | |

| History of RTK-Ag/PCR test | 0.125 | |||

| Yes | 227 | 171 | 56 | |

| No | 41 | 26 | 15 | |

DISCUSSION

This nationwide online survey outlines the fact that, in general, our respondents were highly aware of the need to perform COVID-19 self-tests and were generally willing to pay for the self-test kits. However, subgroup analysis revealed that only half of the respondents with monthly household income less than RM1,000 and 55% of Indian respondents were willing to pay for COVID-19 self-test kits. Publicity efforts by the government and non-governmental agencies across the nation, given the complexity and seriousness of the pandemic at the time of the survey, resulted in good penetration of information towards COVID-19 self-testing policies. Our results on awareness of COVID-19 self-tests were in fact, better than those of studies conducted in Indonesia and United Arab Emirates, in which only 15.53% and 25% of respondents were aware of COVID-19 self-testing, respectively [9][10].

Nevertheless, the extent of Willingness-To-Pay (WTP) based on price differences in our study did not differ significantly from the median WTP among respondents in the Indonesian study (USD 1.5, in approximate RM 6.00 during the period) but was higher than the median WTP reported in a study conducted in Nigeria (USD 1.2, in approximate RM 4.80). This may be explained by the fact that both Malaysia and Indonesia are classified as Upper Middle-Income countries, while Nigeria is a Lower Middle-Income Country, as reported by the World Bank at the time of study. This classification reflected differences in median WTP for COVID-19 self-test kits. It also reflects the affordability and perceived value of the COVID-19 self-test kits, as portrayed in our survey – when the survey was conducted, COVID-19 self-test kits were sold at the price as low as RM 3.00. We believe that this may have influenced the findings of WTP among our respondents.

The attitudes portrayed towards COVID-19 self-tests in our survey generally corresponded to the emergence of the Omicron variant in March 2022 [11], and the stipulations in the Standard Operating Procedures (SOP) for the 4th Phase of National Recovery Plan (Fasa Pemulihan Negara) at the time of the survey [12]. The Omicron variant was found to replicate around 70-fold faster than Delta variant, despite causing milder symptoms, and fewer death and complications [13]. This heightened risk perception likely contributed to a higher willingness to conduct COVID-19 self-tests when necessary. Another online nationwide study evaluating willingness to perform COVID-19 self-testing similarly told that in general, 89.3% of the respondents were willing to perform COVID-19 self-tests [14]. Although international and interstate travelling was permitted for fully-vaccinated individuals (with booster doses) except in areas where Enhanced Movement Control Order (EMCO) were implemented, the requirement to perform COVID-19 self-tests remained high in situations such as international travel, meetings, workshops, or when signs and symptoms of COVID-19 were suspected, as well as for close contacts and during quarantine periods for confirmed cases [12]. This context may synergistically resulted in our respondents’ high willingness to perform self-tests to ensure daily activities, including work, school or business operations, would not be disrupted by COVID-19 infection, reflecting a greater willingness to adapt to the “new norm”. Additionally, the requirement to perform self-tests was mainly attributed to work and organisational needs, or situations with apparent perceived risks, this could explain why the majority of our respondents perceived that COVID-19 self-test kits should also be at least partially funded by their employers, healthcare insurance providers, or the government.

While methodological differences existed in evaluating WTP compared to other similar studies, the finding that female and students had higher odds to pay for COVID-19 self-test kits was somehow unexpected. However, it aligned with the observation that female had a higher risk perception towards COVID-19 infection as compared to males, leading to a greater willingness to invest in COVID-19 self-test kits [14][15]. The correlation between students and WTP for COVID-19 self-test kits may also have related to another study among Malaysian university students, which found that they exhibited high risk perception (indicated by high mean risk perception in the study) towards COVID-19 [16], thereby increasing their willingness to pay for the self-testing kits at an affordable price. Conversely, more commonly observed predictors, such as household income level, surprisingly did not show statistical significance in our survey compared to other studies [8].This could be explained by the general recognition of the importance of COVID-19 self-testing within our society, resulting in a willingness to pay for them – what varied was simply the extent of payment from self-pockets and whether they were partially funded by other parties (e.g. government or employers). Nevertheless, findings from this survey warrant further insights into targeted subsidisation.

While the demand for COVID-19 self-test kits may have declined as the pandemic transitioned into an endemic phase, the findings remain significant in several ways. First, the study provides valuable insights into consumer behaviour and pricing strategies that can guide policymakers in preparing for future pandemics or similar public health emergencies. The high willingness to pay (WTP) demonstrated in this study reflects the public’s readiness to invest in accessible diagnostic tools when faced with infectious threats that may affect their daily activities. Such data offer guidance in crafting strategies to optimise the affordability and accessibility of rapid diagnostic tools during the initial phases of future pandemics, where rapid testing is crucial. Furthermore, it is important to note that the study also highlights the importance of pricing subsidies and contributions from employer or government, which can be generalised to other healthcare commodities. The behavioural predictors identified, such as risk perception and demographic factors, provide a foundation for targeted communication and resource allocation during health crises.

This study is not without limitations. Interpretations from this study may not fully represent the general Malaysian population, as our sample distribution were not stratified according to the proportions of Malaysian population across different states (the majority of the samples were from Kedah) or various demographic characteristics, resulting in a less homogenous sample. Furthermore, we did not evaluate the extent of WTP (as of different level of prices) across different factors and determinants, which is commonly seen in other similar studies among currently available literature. We also did not compute WTP estimates based on any econometric models, such as Tobit or Heckman selection models, which are more robust methods for determining WTP, especially when zero WTP cases occurred in this survey. Nevertheless, serving as a baseline study, we believe the findings from this study can establish a foundation for improvements in future research, including a more inclusive sampling approach and enhanced methodology to provide deeper insights for future studies. Furthermore, longitudinal studies to track changes in willingness to pay and attitudes towards self-testing over time are also warranted, which can help to assess the impact of public health interventions and changes in the situation.

CONCLUSION

This study depicts a high willingness among respondents to perform COVID-19 self-tests, with a willingness to pay for the self-testing kits at a mean maximum price of RM 9.16 (SE = 0.68) and a median maximum price of RM 6.00. While COVID-19 has gradually transitioned into an endemic phase at the time of writing, the WTP findings from this study serve as a valuable reference for price setting, differentiation, and subsidisation of self-test kits in preparation of any potential future emergence of similar pandemics.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflict of interest declared.

REFERENCE

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet (London, England). 2020 Feb;395(10223):497–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30183-5

- World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available from: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases?n=c

- Ministry of Health Malaysia. COVID-19 Dashboard. Available from: https://data.moh.gov.my/dashboard/covid-19

- World Health Organization. SARS-CoV-2 antigen-detecting rapid diagnostic tests: an implementation guide. Country & Technical Guidance – Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). 2020; 1–48. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240017740

- Ministry of Health Malaysia. COVID-19 Rapid Test Kit Antigen (RTK-Ag) Testing for Professional Use. 2022;19–21. Available from: https://covid-19.moh.gov.my/garis-panduan/garis-panduan-kkm/ANNEX-4g-Covid-19-RTK-Ag-21092022.pdf

- Ministry of Health Malaysia. Garis Panduan Pengurusan Kit Ujian Kendiri COVID-19. Available from: https://covid-19.moh.gov.my/semasa-kkm/2021/07/garis-panduan-pengurusan-kit-ujian-kendiri-covid-19-23072021

- Vaughan W, Darling A. The Optimal Sample Size for Contingent Valuation Surveys: Applications to Project Analysis. 2000. http://dx.doi.org/10.18235/0008824

- Kazungu, J., Mumbi, A., Kilimo, P., Vernon, J., Barasa, E., & Mugo, P.. Title Level and determinants of willingness to pay for rapid COVID-19 testing delivered through private retail pharmacies in Kenya. 2021 http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.10.21264807

- Thomas C, Shilton S, Thomas C, Batheja D, Goel S, Mone Iye C, et al. Values and preferences of the general population in Indonesia in relation to rapid COVID-19 antigen self-tests: A cross-sectional survey. Trop Med Int Heal. 2022;27(5):522–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/tmi.13748

- Jairoun AA, Al-Hemyari SS, Abdulla NM, Al Ani M, Habeb M, Shahwan M, et al. Knowledge about, acceptance of and willingness to use over-the-counter COVID-19 self-testing kits. J Pharm Heal Serv Res. 2022;13(4):370–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jphsr/rmac037

- Ministry of Health Malaysia. Penularan Sub-Lineage Variant Of Concern (Voc) Omicron Ba.2 Dan Kesan Kesihatan Awam. 2022. Available from: https://covid-19.moh.gov.my/semasa-kkm/2022/03/penularan-sub-lineage-variant-of-concern-voc-omicron-ba-2-dan-kesan-kesihatan-awam

- Council MNS. Pelan Pemulihan Negara (PPN) – SOP Fasa 4. 2022. Available from: https://covid-19.moh.gov.my/faqsop/pelan-pemulihan-negara-sop-fasa-empat

- Chavda VP, Bezbaruah R, Deka K, Nongrang L, Kalita T. The Delta and Omicron Variants of SARS-CoV-2: What We Know So Far. Vaccines. 2022;10(11). https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10111926

- Ng DL, Bin Jamalludin MA, Gan XY, Ng SY, Bin Mohamad Rasidin MZ, Felix BA, et al. Public’s Willingness to Perform COVID-19 Self-Testing During the Transition to the Endemic Phase in Malaysia – A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2023. https://doi.org/10.2147/rmhp.s439530

- Alsharawy A, Spoon R, Smith A, Ball S. Gender Differences in Fear and Risk Perception During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front Psychol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.689467

- Wong CY, Tham JS, Foo CN, Ng FL, Shahar S, Zahary MN, et al. Factors influencing COVID-19 vaccination intention among university students: A cross-sectional study in Malaysia. Biosaf Heal. 2023;5(1):37–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bsheal.2022.12.005

Please cite this article as:

Norazila Abdul Ghani, Nur Afini Mohamad Nizam, Nik Alya Syakirah Nik Ahmad Faris, Zarmisha Zakaria and Cherh Yun Teoh, Public’s Willingness to Pay for COVID-19 Self-Test Kits in Malaysia: A Web-Based Survey. Malaysian Journal of Pharmacy (MJP). 2024;2(10):40-47. https://mjpharm.org/publics-willingness-to-pay-for-covid-19-self-test-kits-in-malaysia-a-web-based-survey/