Abstract

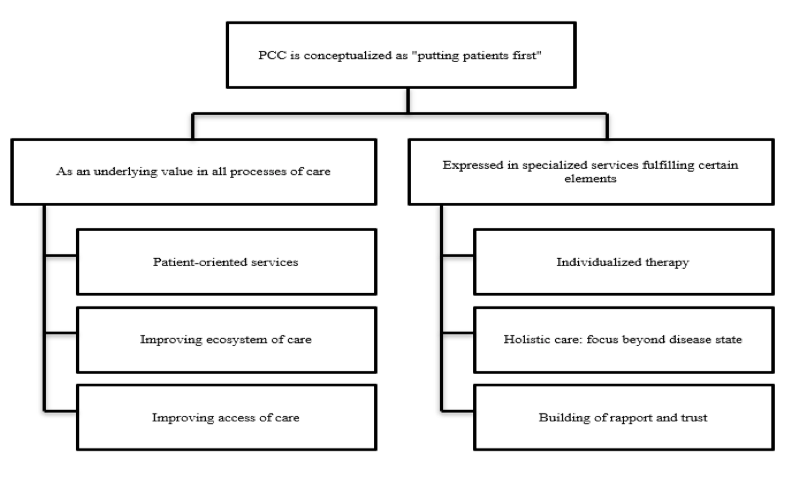

Objective: The objectives of this study were to determine how hospital pharmacists in a developing country interpret the term “patient-centred care (PCC)”, how it was or can be operationalized in hospital pharmacy practice, and barriers faced in delivering such care. Method: A generic qualitative approach was utilized. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with purposively sampled pharmacists from a Malaysian tertiary referral hospital until data saturation, using an interview guide informed by relevant literature. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim, with resultant transcripts subsequently coded and analysed using thematic analysis technique. Result: Fifteen pharmacists were interviewed. Hospital pharmacists conceptualized the basic spirit of PCC as “putting patients first”. On the operationalization of PCC in pharmacy services, one theme/viewpoint was that all processes of care that are patient-oriented, including efforts that facilitate patient convenience, improve ecosystem of care and access of care should be considered as PCC. A contrasting theme only regard pharmacy services demonstrating specific elements, such as provision of individualized therapy, holistic in nature and enable building of rapport and trust between patient and pharmacist, as being consistent with PCC principles. Improving pharmacists’ communication skills, patients’ health literacy and over-reliance on clinicians as well as resource limitations are deemed integral for successful implementation of PCC services. Conclusion: Beyond the concept of putting patients first, there was confusion on the exact concept of PCC and its subsequent operationalization in hospital pharmacy practice. Development of a pharmacy specific PCC framework to serve as a universal blueprint to guide operationalization is recommended.

Introduction

Patient-centred care (PCC) is a healthcare service provision approach that is associated with better health outcomes for patients, improving their satisfaction, well-being, and to a certain extent clinical outcome [1][2][3]. The central philosophy of PCC is providing healthcare tailored to the needs of individual patients, with elements of care widely regarded as fundamental components include involvement of patients in their healthcare, establishment of good relationships between patients and their healthcare providers, healthcare providers having a holistic understanding of their patients, the practice of effective communication as well as patient empowerment[2][4][5]. In PCC, the relationship between both parties has to be egalitarian rather than paternalistic, hence the need for healthcare providers to have the ability to demonstrate empathy, concern and interest toward patients, besides having excellent listening and communication skills [2][6][7]. The overall environment where care takes place has to be conducive, with supportive management and an organizational system that is primed to deliver PCC [8].

Operationalization of PCC is essential to translate PCC from abstract theories into measurable patient outcomes [6]. Scholl et al. (2014) advocated for a unified theory and synchronized ‘language’ of patient-centredness to standardize its’ operationalization, including measurement tools [4]. Quality of PCC is assessed and measured using a mix of patient-reported outcomes and healthcare outcomes indicators [9]. Physician-patient consultations using PCC principles were found to alleviate patients’ discomfort and concern, leading to faster recovery, better emotional well-being and less healthcare utilization [10]. PCC approaches were also found to reduce the need for high-cost, high intensity care such as hospitalization or emergency department visits, as well as resulting in shortened hospital length of stay for those admitted [11][12][13].

However, emphasis and practice of PCC were found to differ between healthcare providers. Studies on doctors emphasized the shared decision-making process between patient and provider, whereas acknowledging patients’ values and beliefs in the care process and providing for their social and emotional needs were the focus of studies on nurses [2]. Unfortunately, the primary focus of the pharmacy profession regarding PCC is not clear. Existing studies focused on specific processes of PCC, for example patient-centred pharmacy consultations [14][15], patient-centred communication [16] and patient-centred professionalism [7][17][18]. Five core elements were proposed by Kibicho and Owczarzak (2012): consideration of the patients’ context, tailored interventions, patient empowerment, collaboration between providers and cultivating sustained relationship with patients [19]. Furthermore, concept and practice can also vary due to cultural difference, and there was a paucity of research on PCC in the developing Asian region [4].

In Malaysia, the integration of PCC into existing government hospital pharmacy practice is not well explored. Malaysia practices a dual healthcare system, with government and private facilities operating in parallel. Government hospitals and health clinics provide a plethora of healthcare services including pharmacy at a heavily subsidized fee, whereas private facilities charge premium prices for their services [20]. Despite this, the pharmacy program at government facilities is comparatively more established, providing extended pharmacy services such as medication therapy adherence clinic (MTAC), ward pharmacy services and home medicines review beyond the basic procurement, ward supply and outpatient dispensing services [21]. To the best of our knowledge, only one study on PCC in the Malaysian pharmacy context was published [15]. The study which focused on pharmacist-patient interaction in MTAC consultations revealed a discordance in the preference and expectations between pharmacists and patients on PCC, further highlighting the importance of contextual consideration in operationalizing the concept [15].

The objectives of this paper were to determine how hospital pharmacists interpret the term “patient-centred care”, how it was or can be operationalized in their daily practice and barriers faced in delivering such care. Comprehension of the concept and its application is important for hospital pharmacists to have a greater impact on patient care. As pharmacists have diverse roles in a hospital, it is also interesting to find out whether it can be practiced in different departments. Elucidation of barriers and suggested facilitators will assist in the future implementation of pharmacy services anchored in PCC.

Method

Study design

A generic qualitative approach was employed as the nature of inquiry did not fit the ambit of established methodologies [22][23][24]. This study was more focused on how to implement PCC, rather than discovery of a theory (grounded theory) or investigation of a lived experience (phenomenology) [23]. A constructionist paradigm was used in this research, where it was tacitly acknowledged that study investigators, being in the same profession as participants, have an influence on the interpretation of the data, with interpretation also equally influenced by the study context and societal beliefs [25].

Study setting and participants

In-depth, face-to-face semi-structured interviews were conducted among pharmacists working in Sarawak General Hospital, a 1003-bedded tertiary referral hospital in Malaysia. There are around 140 pharmacists, including 40 interns in the hospital. Pharmacy services provided include procurement, in-patient medication supply, out-patient dispensing, parenteral and cytotoxic drug reconstitution, clinical pharmacy service as well as MTAC.

Purposive sampling was employed to recruit participants from different pharmacy departments and years of working experience, in order to ensure maximal variation of perspectives [26][27]. Participant selection was carried out by the primary investigator (KBP), being a work colleague of all participants. KBP did not conduct the interviews to minimize elements of bias and coercion; this procedure was done by the other 2 co-investigators (AF and CMW), who were pharmacy interns. AF did the first 4 interviews; subsequent interviews were conducted by CMW. Interview training was provided by KBP, who had experience conducting similar qualitative research. Both interviewers did a practice interview before commencing actual interviews.

Data collection

A semi-structured interview guide (Table I.) was constructed by KBP and AF based on the study objectives and available literature, primarily Scholl et al. (2014), Constand et al. (2014) and Kitson et al. (2012). Interviews were conducted from September 2018 until June 2019, audio-recorded and then transcribed verbatim by AF and CMW. Denaturalized transcription was used as only the content of the interviews was of interest [28]. All transcripts were checked by KBP for errors before being analysed.

| Num. | Question |

| 1. | What do you understand about patient-centred care? |

| 2. | What do you think are the essential components of patient-centred care? |

| 3. | How do you practice patient-centred care in your daily pharmacy work? |

| 4. | Do you think pharmacists are in a position to provide patient centred care? |

| 5. | Generally, what do you think about the current level of patient-centred care among pharmacists and pharmacy-users in Malaysian government hospitals? |

| 6. | What are the current practices that are aligned with patient-centred care? |

| 7. | What is your personal opinion on incorporating components of patient-centred care into the pharmacy service? |

| 8. | As far as you know, what are the possible challenges faced in delivering patient-centred care? |

| 9. | Do you think the current pharmacy work culture is suitable for patient-centred care? |

| 10. | What are the current system artefacts that constrained patient-centred care? |

| 11. | What can we do to overcome the challenges? |

| 12. | How do you think we can best manage the trade-off between providing a fast and efficient service and spending time to incorporate patient centred care elements in our service? |

| 13. | What do you think are the expectations of patients regarding patient-centred care with respect to pharmacy services? |

| 14. | What we can do to improve the acceptance of patients with regards to patient-centred care? |

Data analysis

Data analysis was carried out using thematic principles recommended by Braun and Clarke (2006). This method was chosen as it is widely used and not linked to any theory nor epistemology, hence suitable for generic qualitative research [29]. After each interview, the resultant transcript was reread multiple times and compared to previous transcripts to enhance interpretation and structuring into themes [30]. Coding was carried out independently by KBP and CMW to reduce bias. Discussion was however held after reading or coding each transcript to determine areas to be further explored in subsequent interviews (iterative process) [31]. After data saturation was deemed reached, both investigators came up with their own thematic maps and candidate themes and sub-themes, which were discussed and consolidated with inputs from AF. Throughout the process, investigators were constantly mindful to give fair dealing to the diverse viewpoints of participants and reflect on how their preconceived notions on PCC guided interpretation. Transcribing and coding were facilitated by Microsoft Word, whereas thematic analysis was carried out using Microsoft Excel. The conduct and reporting of this study were based on the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) [32].

Ethical consideration

Conduct of this research was registered with the Malaysian National Medical Research Register (NMRR-18-1550-42239) and was approved by the Medical Research and Ethics Committee (MREC), Ministry of Health Malaysia [Ref:KKM/NIHSEC/P18-1490(11) dated August 14, 2018]. All participants gave informed consent to participate in this research and be audio-recorded.

Result

A total of 15 respondents were interviewed before data saturation, defined as no new significant codes emerging from two consecutive interviews, was deemed reached [33]. Summarized characteristics of respondents are available in Table II. No potential participants refused to participate in the study. All interviews were conducted in English in enclosed rooms within the hospital to minimize disruption. No other personnel besides the interviewer and participant were present during each interview. Interviews were between 30-45 minutes long. No repeat interviews were carried out.

Participants conceptualized the basic spirit of PCC as “putting patients first”, describing it as providing optimal care for patients by focusing on their feelings and needs. In a PCC focused pharmacy, pharmacy services provided revolve around and are responsive toward patients’ requirements foremost.

“Whatever we do, we have to think about the patient, in terms of patient’s safety, in terms of patient’s benefits, everything related for the purpose of producing a good outcome for the patient.” [PC8] However, beyond this basic concept, understanding of participants diverged. Two main themes dominate how PCC is expressed in pharmacy services, namely as an underpinning value guiding all processes of care, or manifest in specific pharmacy services (Figure I.).

| Participant No. | Current pharmacy dept. | Years of working experience | Involvement in MTAC | Working experience in other institutions | Gender |

| PC1 | Clinical | 7 | Yes | No | Female |

| PC2 | Oncology pharmacy | 10 | No | Yes | Female |

| PC3 | Outpatient | 7 | Yes | Yes | Female |

| PC4 | Outpatient | 11 | No | Yes | Male |

| PC5 | Drug Info | 7 | Yes | Yes | Female |

| PC6 | Clinical | 6 | No | Yes | Female |

| PC7 | Clinical | 5 | Yes | Yes | Male |

| PC8 | Outpatient | 2 | No | No | Female |

| PC9 | Inpatient | 21 | No | Yes | Female |

| PC10 | Inpatient | 4 | No | No | Female |

| PC11 | Inpatient | 4 | No | Yes | Female |

| PC12 | Clinical | 15 | No | Yes | Female |

| PC13 | Inpatient | 4 | No | No | Female |

| PC14 | Outpatient | 7 | Yes | Yes | Female |

| PC15 | Clinical | 5 | No | No | Female |

Theme 1: PCC as an underpinning value in all processes of care

1. Patient-oriented services

Participants expressed that any process of care that is patient-oriented during its operationalization constitutes PCC. This includes ensuring basic safety of patients, for example dispensing correct medications; as well as making services convenient to patients, such as providing alternative methods for patients to collect their repeat medications so that they do not have to wait in line at the pharmacy.

“I think in all our work, there are some elements of PCC, if in-inpatient, [during] filling medications… we always come across many prescriptions that we think are not right, we will intervene. That is also a part of PCC, rather than just looking at the prescriptions and following blindly whatever that was written.” [PC8]

“[Pharmacy Value Added Services (VAS)] can help patients who are inconvenienced to come and collect their medications, like we post their medications [via postal service], and also they can [pre-inform] they want to collect within the next 3 days, so that we can prepare, so that when they come, they no need to wait. For me, VAS is one type of PCC.” [PC11]

2. Improving ecosystem of care

Efforts that improve work efficiency and indirectly lead to better patient care were also considered as PCC. This includes the use of technology such as robotized filling of medicines to free up pharmacists’ time, enabling them to concentrate on patient related activities. Building an effective communication system to facilitate sharing of information between healthcare professionals across facilities, in order to reduce information gaps that hamper provision of optimal care was also highlighted as being essential.

“If you want PCC, sometimes it is more like developing a system to link between the facilities. For example, if this patient is allergic to paracetamol, if there is a system linked between facilities, the facility can access the data.” [PC6]

3. Improving access to care

Some participants have a health system-wide view on the practice of PCC, believing it includes efforts to bring health services nearer to patients, such as enhancing accessibility for those who are not able to visit hospitals due to physical disabilities. They also believed that the current government subsidized public healthcare system is aligned with the concept of PCC, as it ensures that the poor have equal access to healthcare and medicines.

“…especially psychiatric patients because some of them are like they don’t want to go for follow-ups, maybe due to the worry how other people look at them, they don’t want to come to hospital. For those patients, you need to visit them and counsel them. If not, they will default for sure.” [PC15]

Theme 2: PCC expressed in specialized services fulfilling certain elements

Participants highlighted medication therapy adherence clinics (MTAC), clinical pharmacy services and home medicines review (HMR) as pharmacy services most aligned with PCC. These services have elements of care that are similar:

1. Individualized therapy

Proponents of this view opined that PCC services must have an element of individualized care in them, where pharmacists interact with patients on a one-to-one basis, enabling personalization and tailoring of services to match patients’ needs. For example, clinical pharmacy services were deemed PCC oriented as pharmacists work in an environment with minimal barriers for them to care for and communicate with patients, and for patients to approach them. In contrast, dispensary pharmacists are hindered by a physical counter and pressure to dispense quickly, reducing their tendency to individualize treatment plans.

“(Roles in PCC vary) depending on which department you are working, like for example, inpatient [pharmacy], our roles will be lesser compared to clinical pharmacists… I think the person who can play the most role in PCC are the clinical pharmacists. They are exposed to the patients the most.” [PC11]

2. Holistic care: focus beyond disease state

PCC means taking into account patients’ psychological and social issues, rather than merely focusing on their disease state and medications while caring for them. This is based on the belief that external issues can also significantly impact the health outcome of patients. For example, in asthma or diabetes mellitus MTAC, participants envisioned a bigger role for pharmacists in encouraging patients to make lifestyle modifications to better control their disease. Pharmacists also have signposting function, playing a pivotal role in referring patients to other healthcare professionals for specific needs.

“When you see patient in the ward or MTAC…you have more time to sit down with them, you explore more other than [just] giving medication counselling, you actually explore more like how is patient doing at home, how is patient’s acceptance towards his disease…because a disease is more than just a disease itself, it affects the patient’s life.” [PC4]

3. Building of rapport and trust

Good communication forms the foundation of PCC, however beyond conveying correct messages to patients to facilitate informed choices and providing effective education on their medicines, communication in PCC services form bonds and subsequently build trust between pharmacists and patients. Establishment of trust between both parties will render patients more open and receptive toward pharmacists’ suggestions, and more likely to make the necessary changes to improve their health outcomes.

“If you try to forcefully educate someone, they might not be receptive to it… [but] if you communicate well with the patients, you actually kind of develop a relationship with the patients which will make them trust you more and you tend to listen to someone’s advice if you know that person, instead of a stranger.” [PC13]

Theme 3: Barriers and facilitators of PCC in the pharmacy

Participants highlighted several prominent factors that were felt to hinder the provision of PCC in the hospital pharmacy setting and also suggested solutions:

1. Communication skills

Excellent communication ability, including the ability to listen is regarded by participants as a rudimentary skill pharmacists should have to provide PCC. This will enable better understanding of patients’ needs and obtaining sufficient information to uncover underlying issues, including during patient counseling. Participants acknowledged that most pharmacists still have room for improvement in this area, and suggested more workshops, hands-on practices and role-modelling to improve this skill. Rotating between departments was also suggested as a way to ensure all pharmacists have a chance to participate in PCC activities.

“Sometimes, they (patient) abandon the medications not because they don’t want to listen, it’s just [that] they don’t have the full understanding. Might be something happened to the quality of the counseling, whether the pharmacist made the patient understand what the medication is for.” [PC6]

“Certain people (pharmacists) need training not just knowledge-wise but also how to deliver [the message] to the patients effectively… Those kinds of courses and workshops, [they] can be asked to attend.” [PC8]

2. Beyond “doctor, doctor”

Participants noted that the provision of PCC requires patients’ involvement in the decision-making process regarding their care. However, they conceded that the current healthcare system is clinician-centred, with the belief that “doctors know best” being pervasive and prominent. Patients with insufficient health literacy do not feel confident to make their own healthcare decisions. Many patients are also not familiar with pharmacists’ extended roles beyond dispensing. Increased pro-activeness among pharmacists to promote their roles was suggested, including asking patients about their needs to overcome their reservations. Holding awareness campaigns to further promote the profession, including via social media, was also recommended.

“Some of them they will ask: you are doctor or pharmacist? If pharmacist they don’t bother to tell you anymore… They thought that we only give medications, give medications. They think we are just dispensing machines.” [PC15]

3. Institutional barriers

Various institutional barriers, namely insufficient manpower, facilities, use of technology and organizational support are also present. Participants lamented that the high pharmacist-to-patient ratio and lack of counseling rooms limit opportunities to conduct PCC activities. In terms of organizational support, there is a need to have key performance indicators (KPIs) that are more aligned with PCC and increased emphasis on PCC activities. Nevertheless, work re-engineering to facilitate the provision of PCC was actively practiced, for example conducting group counseling to save time or scheduling patient counseling at off-peak hours to spend more time with patients, as participants believed that this concept is the future of pharmacy. Participants also acknowledged that they need to work hard on constantly improving their competency, in order to be able to work more efficiently.

“To be frank, we are all chasing KPIs, trying to achieve our personal targets…the KPI 30 minutes to dispense…we will keep chasing like, oh 30 minutes, then we will rush our job like that, so will [be] prone to error… [patient-centred KPI will be] like how many patients that we had counselled, that we really sit down and counsel.” [PC14]

Discussion

Our findings highlighted two different views on the practice of PCC in the pharmacy setting. Some participants opined that PCC is practiced by re-engineering all pharmacy services to have a “patient first” orientation while another group of participants believed that PCC only manifests in services that fulfil key elements such as listening, communicating, empowering, educating and collaborating with patients. This demonstrates a lack of deep appreciation or true understanding of what PCC entails, or a reflection of the current ambiguity shrouding its definition, as well as how it should be practiced in the pharmacy setting [34].

Based on current literature, for a particular service to be considered as PCC, key elements of the concept must be present during service delivery [4][34][35]. Hence patient safety efforts and services facilitating collection of repeat medications, despite being patient-centred do not make the cut as patient-centred care. Likewise, infrastructure enhancements such as the utilization of drug filling robots and electronic health records only indirectly facilitate PCC by freeing pharmacists’ time to engage with patients [34]. For dispensing services to be regarded as PCC, elements of patient collaboration and empowerment, as well as treatment individualization need to exist. For example, patients had to be asked whether they wish to discuss their treatment, rather than having pharmacists forcing the same generic counseling scripts to them [36]. This distinction had to be clarified among pharmacists, as a correct grasp of the concept is a prerequisite for proper operationalization.

Participants mainly discussed PCC based on current available services, i.e., whether and why an existing service is considered PCC, rather than how PCC elements can be incorporated into different facets of pharmacy practice, or what new services that are aligned with the concept can be introduced. Most participants cited MTAC as the quintessential PCC service, as it involves one-to-one interaction between pharmacist and patients with chronic diseases over multiple encounters, enabling a reciprocal, long-term relationship to be established [15][37]. Patient empowerment in the form of self-management training was also provided, such as self-monitoring of blood glucose and foot care for diabetic patients [38]. Nevertheless, alignment of MTAC with PCC principles can be enhanced by making the service open and accessible to all patients to self-enrol rather than provider initiated, and shifting the focal point from the medication regime to the patient [19]. For in-patient and ward pharmacy services, there are various services that can be introduced or adapted to be more patient-centred, including polypharmacy or multi-morbidity management, transition of care coordination during admission and discharge to ensure continuity of care, as well as medication de-prescribing [39]. For out-patient pharmacy service, patients’ issues with route of administration, medication timing, potential and current side effects as well as management of lifelong chronic medications can be targeted [40].

It is heartening that participants demonstrated favourable attitude towards PCC and agreed that it is the future of pharmacy practice, yet translating this attitude fully into actual practice is a challenge, as testified by global and local experiences [40][41]. For instance, some pharmacists may yet to master the level of communication skills critical to the provision of PCC. Good communication skills foster the establishment of trust between patients and healthcare providers, as well as facilitate shared decision making [2][4]. Hence it is essential that more training focusing on improving pharmacists’ communication skills is provided. Besides, health coaching techniques, which seek to modulate patients’ beliefs, values and attitudes to alter their health behaviour can also be introduced. Incorporation of health coaching during patient interaction was found to improve healthcare providers’ ability to provide PCC [42].

Patients’ readiness to be involved in shared decision making and make informed decisions on their healthcare are important elements of PCC [43]. Unfortunately, in Malaysia, limited health literacy among the general public hindered their participation in healthcare decision making [41][44]. Patients do not have sufficient understanding of their diseases and medicines to enable a constructive discussion of their condition. Patient empowerment at the grassroots level on medicines use is important to alleviate this lack of awareness, for example organization of “Know Your Medicines” campaigns which aim to inculcate basic knowledge of medicines use among the Malaysian public [45]. At the institutional level, the lack of pharmacy resources, primarily manpower and facilities are recurring themes in the literature on PCC implementation in healthcare organizations [46][47]. Increased time needed to interact and care for patients is expected when PCC is practiced, even though there were suggestions that redesign of services to be patient-centred may not require additional manpower, and even result in efficacy gains [38][40][47]. Nonetheless, additional resources including manpower and facility upgrades are often considered necessary by healthcare workers to implement new services, hence availability of resources will directly impact their receptiveness and accommodation of these services [48].

Strengths and limitations

This study is one of the few focusing on PCC in developing Asian countries. It explored the conceptualization and operationalization of PCC in all hospital pharmacy services, expanding on the work of Ng et al. (2019) which only focused on MTAC consultations. Limitation wise, the study was confined to a single institution, which runs the risk of participants’ perspectives being moulded by the culture of the institution. This was mitigated by recruitment of participants who had previously served in different institutions in wide-ranging capacities, diversifying the experiences and viewpoints. Findings were derived from analysis of hospital pharmacists’ perceptions, which may be tainted by social desirability bias. As noticed during the conduct of this research, most participants regarded their current duties as PCC. Triangulation using direct observation of actual behaviour or critical incident analysis may be useful in future studies. Patients’ perspectives and needs for pharmacy related PCC are equally important, and a similar study exploring their viewpoints will also triangulate the findings of this research and provide greater insights.

Conclusion

Beyond the concept of putting patients first, there is confusion on the exact concept of PCC and its subsequent operationalization in hospital pharmacy practice. There is also a lack of ideas on how it can be incorporated in existing pharmacy services. There is a need to develop a universal framework to serve as reference for the development of patient-centred pharmacy services or incorporation of PCC elements into current pharmacy processes, which is important to ensure consistent definition, operationalization and evaluation of these services.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the Director General of Health Malaysia for his permission to publish this article. We would also like to acknowledge Natasha Ngumbang, Grace Wong Su Lin and Phang Sze Ying, pharmacists at Sarawak General Hospital for their assistance in drafting the research proposal, as well as participants for sharing their experiences and perspectives.

Conflict of Interest

This study has no conflict of interest. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Reference

- Pelzang R. Time to learn: understanding patient-centred care. Br J Nurs.2010;19:912-917. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2010.19.14.49050

- Kitson A, Marshall A, Bassett K, Zeitz K. What are the core elements of patient-centred care? A narrative review and synthesis of the literature from health policy, medicine and nursing. J Adv Nurs. 2013;6:4-15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06064.x

- Rathert C, Wyrwich MD. Patient-centered care and outcomes: a systematic review of literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2012;70:351-379. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558712465774

- Scholl I, Zill JM, Harter M, Dirmaier J. An integrative model of patient centeredness – a systematic review and concept analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e107828. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0107828

- Constand MK, MacDermid JC, Bello-Haas VD, Law M. Scoping review of patient-centered care approaches in healthcare. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:271. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-271

- Mead N, Bower P. Patient-centredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Soc Sci Med, 2000;51:1087-1110. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00098-8

- Hutchings HA, Rapport FL, Wright S, Doel MA, Wainwright P. Obtaining consensus regarding patient-centred professionalism in community pharmacy: nominal group work activity with professionals, stakeholders and members of the public. Int J Pharm Pract. 2010;18(3):149-158. https://doi.org/10.1211/ijpp.18.03.0004

- McCormack B, McCance T V. Development of a framework for person-centred nursing. J Adv Nurs. 2006;56(5):472-479. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04042.x

- Tzelepis F, Sanson-Fisher RW, Zucca AC, Fradgley EA. Measuring the quality of patient-centered care: why patient-reported measures are critical to reliable assessment. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:831.

- Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, McWhinney IR, Oates J, Weston WW, Jordan J. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2000;49:796-804 https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S81975

- David G, Gunnarsson C, Saynisch PA, Chawla R, Nigam S. Do Patient-Centered Medical Homes Reduce Emergency Department Visits? Health Serv Res. 2015;50:418-439. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12218

- Ekman I, Wolf A, Olsson LE, Taft C, Dudas K, Schaufelberger M, Swedberg K. Effects of person-centred care in patients with chronic heart failure: the PCC-HF study. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1112-9. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehr306

- Hansson E, Ekman I, Swedberg K, Wolf A, Dudas K, Ehlers L, Olsson L. Person-centred care for patients with chronic heart failure – a cost-utility analysis. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2016;15:276-284. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474515114567035

- Wolters M, van Hulten R, Blom L, Bouvy ML. Exploring the concept of patient centred communication for the pharmacy practice. Int J Clin Pharm. 2017;39:1145-1156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-017-0508-5

- Ng YK, Shah NM, Loong LS, Pee LT, Chong WW. Patient-centered care in the context of pharmacy consultations: A qualitative study with patients and pharmacists in Malaysia. J Eval Clin Pract. 2020;1-10. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.13346

- Murad MS, Chatterley T, Guirguis LM. A meta-narrative review of recorded patient–pharmacist interactions: Exploring biomedical or patient-centered communication? Res Social Adm Pharm. 2014;10:1-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2013.03.002

- Elvey R, Hassell K, Lewis P, Schafheutle E, Willis S. Patient-centred professionalism in pharmacy: values and behaviours. J Health Organ Manag 2015;29:413-430. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHOM-04-2014-0068

- Rapport F, Doel MA, Hutchings HA, Wright S, Wainwright P, John DN, Jerzembek GS. Eleven themes of patient-centred professionalism in community pharmacy: innovative approaches to consulting. Int J Pharm Pract. 2010;18:260-268. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-7174.2010.00056.x

- Kibicho J, Owczarzak J. A patient-centered pharmacy services model of HIV patient care in community pharmacy settings: a theoretical and empirical framework. AIDS patient care and STDs. 2012;26(1):20-8.

- Jaafar S, Mohd Noh K, Abdul Muttalib K, Othman NH, Healy J. Malaysia health system review. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2013. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2011.0212

- Hassali MAA, Shafie AA, Ooi GS, Wong ZY. Pharmacy practice in Malaysia. In Fathelrahman AI, Mohd Ibrahim MI, Wertheimer AI, eds. Pharmacy Practice in Developing Countries: Achievements and Challenges. London: Elsevier Inc; 2016;23-40.

- Caelli K, Ray L, Mill J. ‘Clear as Mud’: towards greater clarity in generic qualitative research. Int J Qual Methods. 2003; 2:1-13. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690300200201

- Bellamy K, Ostini R, Martini N, Kairuz T. Seeking to understand: using generic qualitative research to explore access to medicines and pharmacy services among resettled refugees. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38:671-5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-016-0261-1

- Kahlke RM. Generic qualitative approaches: Pitfalls and benefits of methodological mixology. Int J Qual Methods. 2014;13:37-52. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691401300119

- Levers MJ. Philosophical paradigms, grounded theory, and perspectives on emergence. SAGE Open. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244013517243

- Etikan I, Musa SA, Alkassim RS. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am J Theor Appl Stat. 2016;5:1-4. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

- Onwuegbuzie AJ, Collins KMT. A typology of mixed methods sampling designs in social science research. Qual Rep. 2007;12:281-316.

- Oliver DG, Serovich JM, Mason, TL. Constraints and opportunities with interview transcription: towards reflection in qualitative research. Soc Forces. 2005;84:1273-89. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2006.0023

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77-101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Burnard P, Gill P, Stewart K, Treasure E, Chadwick B. Analysing and presenting qualitative data. Br Dent J. 2008;204:429-432. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2008.292

- Fossey E, Harvey C, McDermott F, Davidson L. Understanding and evaluating qualitative research. Aust Nz J Psychiat. 2002;36:717-732.

- O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89:1245-51. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1614.2002.01100.x

- Bowen, GA. Naturalistic inquiry and the saturation concept: A research note. Qual Res. 2008;8:137-152. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794107085301

- Epstein RM, Street Jr RL. The values and value of patient-centered care. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9:100-103. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1239

- Tsuyuki RT, Krass I. What is patient-centred care? Can Pharm J (Ott). 2013;146:177-180. https://doi.org/10.1177/1715163513494591

- Barnett NL, Flora K. Patient-centred consultations in a dispensary setting: a learning journey. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2017;24:107-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ejhpharm-2016-000929

- McCullough MB, Petrakis BA, Gillespie C, Solomon JL, Park AM, Ourth H, Morreale A, Rose AJ. Knowing the patient: A qualitative study on care-taking and the clinical pharmacist-patient relationship. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2016;12:78-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2015.04.005

- [38] Bauman AE, Fardy HJ, Harris PG. Getting it right: why bother with patient-centred care? Med J Aust. 2003;179:253-256. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05532.x

- Barnett NL. Person-Centred approach to Pharmacy Practice [dissertation]. London, England: Kingston University; 2017.

- Ward J, Kalsi D, Barnett N, Fulford BK, Handa A. Shared decision making in chronic medication use: Scenarios depicting exemplary care. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2020;16:108-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2019.04.047

- Ali A, Meyer C, Hickson L. Patient-centred hearing care in Malaysia: what do audiologists prefer and to what extent is it implemented in practice? Speech Lang Hear. 2018;21:172-82. https://doi.org/10.1080/2050571X.2017.1385167

- Barnett NL, Leader I, Easthall C. Developing person-centred consultation skills within a UK hospital pharmacy service: evaluation of a pilot practice-based support package for pharmacy staff. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2019;26:93-100. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ejhpharm-2017-001416

- Pulvirenti M, McMillan J, Lawn S. Empowerment, patient centred care and self-management. Health Expect. 2014;17:303-10. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-7625.2011.00757.x

- Ng CJ, Lee PY, Lee YK, Chew BH, Engkasan JP, Irmi ZI, Hanafi NS, Tong SF. An overview of patient involvement in healthcare decision-making: a situational analysis of the Malaysian context. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:408. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-408

- Malaysian National Medicines Policy, 2nd edition. Malaysia: Ministry of Health Malaysia; 2013.

- American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on Person-Centered Care. Person-centered care: A definition and essential elements. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:15-8. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13866

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Patient-centred care: improving quality and safety through partnerships with patients and consumers. Sydney: ACSQHC; 2011.

- Low LL, Ab Rahim FI, Johari MZ, Abdullah Z, Aziz SH, Suhaimi NA, Jaafar N, Hanafiah AN, Kong YL, Mahmud SH, Zulkepli MZ. Assessing receptiveness to change among primary healthcare providers by adopting the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR). BMC Health Serv Res.. 2019;19:497. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4312-x

Please cite this article as:

Boon Phiaw Kho, Mei Wen Chai and Adelyn Yin Yin Foo, A Qualitative Study Exploring Pharmacists' Perspectives on the Conceptualization and Operationalization of Patient-Centred Care in the Hospital Pharmacy Setting. Malaysian Journal of Pharmacy (MJP). 2021;2(7):13-21. https://mjpharm.org/a-qualitative-study-exploring-pharmacists-perspectives-on-the-conceptualization-and-operationalization-of-patient-centred-care-in-the-hospital-pharmacy-setting/