Abstract

Chronic pain has a significant impact on sufferers’ quality of life. Furthermore, treatment inadequacies are often reported in the literatures. This study aims to investigate the prevalence of the different dosing behaviors in analgesics use in chronic, non-cancer pain and their correlation to pain control. This is a cross-sectional study and a convenience sampling method was applied. Brief Pain Inventory- Short Form and Pain Management Index was computed to assess pain control. Statistical analysis was performed with Pearson chi-square test and alpha value was set at 0.05. A total of 127 patients were analyzed. 70.9% of the patients reported inadequate pain control with their prescribed analgesic(s). 88.2% patients only took oral analgesics whenever they felt the pain while 11.8% patients took around-the-clock despite the absence of pain. Among them, 11.8-34.7% of patients did not follow their prescriber’s instruction for oral and topical analgesic use respectively. However, no statistically significant result was found between the dosing behaviors and pain control (p>0.95). It was also reported that 98% of patients were not aware of the maximum daily dose of their prescribed analgesic(s). The prevalence of ‘as needed’ dosing is higher than around-the-clock dosing in the management of chronic, non-cancer pain, with deviation from the prescribed instructions between 11.8-34.7%. However, those differences were not significantly associated with the pain control.

Introduction

Pain is often a symptom reported by patients suffering from various clinical conditions. The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) defines pain as an ‘unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage’ [1]. Pain should not be viewed as merely a symptom, as pain can persist for a long period of time even after an underlying injury or disease has resolved. When the pain persists for at least three months, it is categorized as chronic pain, and the cause can be cancerous or non-cancerous origins.

Among Asian adults, Malaysia has one of the lowest prevalence of chronic pain at 7.1%, in comparison to Northern Iraq (72%), Cambodia (48%) and Singapore (8.7%). However, the pain prevalence is notably higher among the geriatric population (42 to 90.8%) [2].

Pain should not be overlooked. This is because people with chronic pain were often reported to have a poor quality of life due to immobility, disability, disturbed sleep, isolation, anxiety, frustration, depression, poor appetite and nutrition, increased susceptibility to disease, dependence on medication, and long-term medical care [3-6]. Specifically, for chronic non- cancer pain (CNCP), it was found that as much as 80.8% of patients whose activities of daily living were affected by pain [7], further highlighting the inadequacy of pain management in this patient cohort.

Pain management starts with pain assessment since the choice of analgesic will be different based on the pain score. Pain assessment can be performed with Numerical Rating Scale (NRS), which uses an 11-point scale. Pain can range from none (score zero) to the worst pain ever possible (score ten).[8] After the determination of a pain score, the next step in pain management is analgesic selection. To guide analgesic selection, National Health Service (NHS) United Kingdom

(UK) devised a treatment guideline for CNCP. In the guideline, it was recommended that every treatment should start with paracetamol, and this medication should be added to a subsequent regimen for its synergistic effect. If the pain persists, or not properly controlled, non-steroidal anti- inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or weak opioids can be prescribed. If the NSAIDs or weak opioids are still ineffective, a more powerful opioid like morphine or fentanyl should be given to the patient [9].

CNCP treatment is mostly based on the principles behind the World Health Organization (WHO) analgesic ladder [10], which was originally developed for cancer pain management. Because of this origin, the majority of institutional guidelines, reviews, and training manuals advocate the effectiveness of regular analgesic in both cancerous and non-cancerous chronic pain [9,11-14]. Unfortunately, in Malaysia, it was found that only 4.2 to 4.4% of the population take their analgesic regularly in chronic pain [15-16], which is lower than a chronic pain prevalence of 7.1% in the country. Therefore, this study was initiated to investigate the prevalence of the different dosing behaviors in analgesics use in CNCP outpatients and their correlation to pain control.

Method

Study design

This was a single-center, cross-sectional study conducted in the outpatient pharmacy department of Kuala Lipis Hospital in Malaysia. Convenience sampling was used to recruit study participants. Possible sampling bias was minimized by consistently recruiting patients during their clinic appointments, which are 8 a.m. to 1 p.m. from Mondays to Fridays, excluding public holidays.

Sample Size Estimation

With an estimated prevalence of chronic pain at 7.1% [2], a confidence level of 95%, and a confidence limit of 5%, a minimum sample size of 101 was calculated to provide ≥80% power [17]. After considering a possible 15% dropout rate, the final calculated sample size was 117 subjects.

Study Subjects

All patients who presented to the outpatient pharmacy with a valid prescription were screened for eligibility. Patients who took at least one analgesic for a minimum of three months, as verified by the pharmacy dispensing record, were invited for study participation. We excluded patients who were less than eighteen years old, pregnant women, and those with a diagnosis of cancer-related pain.

Measurement of Outcomes

All study subjects were assisted by researchers to fill in a questionnaire. The questionnaire consisted of three sections. The first section consisted of baseline demographic characteristics of study subjects such as gender, age, race, occupational status, and pain diagnosis. The second section was about study subjects’ pain management details such as the prescribed analgesic(s) (name and dosage form), dose, actual dose taken for each analgesic, and whether they used over-the- counter (OTC) analgesic and complementary medicines. If the prescribed instruction of the analgesics was ‘as needed’, we further investigated if the respondents can correctly identify the maximum allowable daily dose. Information for the second section was first extracted from medical records and pharmacy dispensing record, before verbally verified with the patients. The third part was the Brief Pain Inventory- Short Form (BPI- sf) to assess pain among study subjects. BPI-sf is a 9-item self- administered questionnaire and is chosen for this study due to its ability to assess the totality of pain experience (minimum, maximum, average and current pain score) [18]. The patient is asked to rate their worst, least, average, and current pain intensity, list current treatments and their perceived effectiveness. The Malay version of the BPI previously validated in local population [19] was used in this study. A pilot test of fourteen patients gave a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.677.

We used the pain management index (PMI) to assess the adequacy of pain control. The index is constructed upon the patient’s worst pain level in the last twenty-four hours recategorized as zero (no pain), one (pain score one to three, mild pain), two (pain score four to seven, moderate pain), or three (pain score eight to ten, severe pain). To compute the index, the new pain level was then subtracted from the most potent level of their prescribed analgesic categorized as zero (no analgesic drug), one (non-opioid), two (a weak opioid), or three (a strong opioid). Ranging from -3 (a patient with severe pain receiving no analgesic) to +3 (a patient receiving morphine or an equivalent and reporting no pain), a score of zero and higher (positive value) indicated acceptable pain control with analgesic while a negative value suggested suboptimal pain control [20-21]. The index was computed with Microsoft Excel function and the accuracy of calculation was then manually cross-checked by the researchers.

Two dosing categories, regular or as needed, were used to investigate the prevalence of dosing deviation. The dosing behavior was classified as regular if the patient took analgesics at a fixed interval (once daily or several times a week) despite the absence of pain. On the other hand, if analgesics were used only in the presence of pain sensation, the dosing behavior was classified as ‘as needed’.

Statistical Analysis

Data was analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21 (IBM Corp. Released 2012. IBM SPSS Statistics(a) for Windows, Version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). Descriptive statistic was used to summarize the demographic data in mean, standard deviation (SD), and proportion. Pain score was presented in median and interquartile range (IQR). Pearson chi-square and fisher’s exact test were used to study the relationship between the dosing deviation and PMI. All the p- values were two-tailed and statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Ethics Approval

The study was registered under Malaysia National Medical Research Registry (NMRR-16-1880-32144) and approved by the Medical Research and Ethics Committee Malaysia ((6)KKM/NIHSEC/P16-1549). All participants provided written informed consent before enrolment, and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Result

Study Subjects

We approached a total of 130 patients. Three patients refused

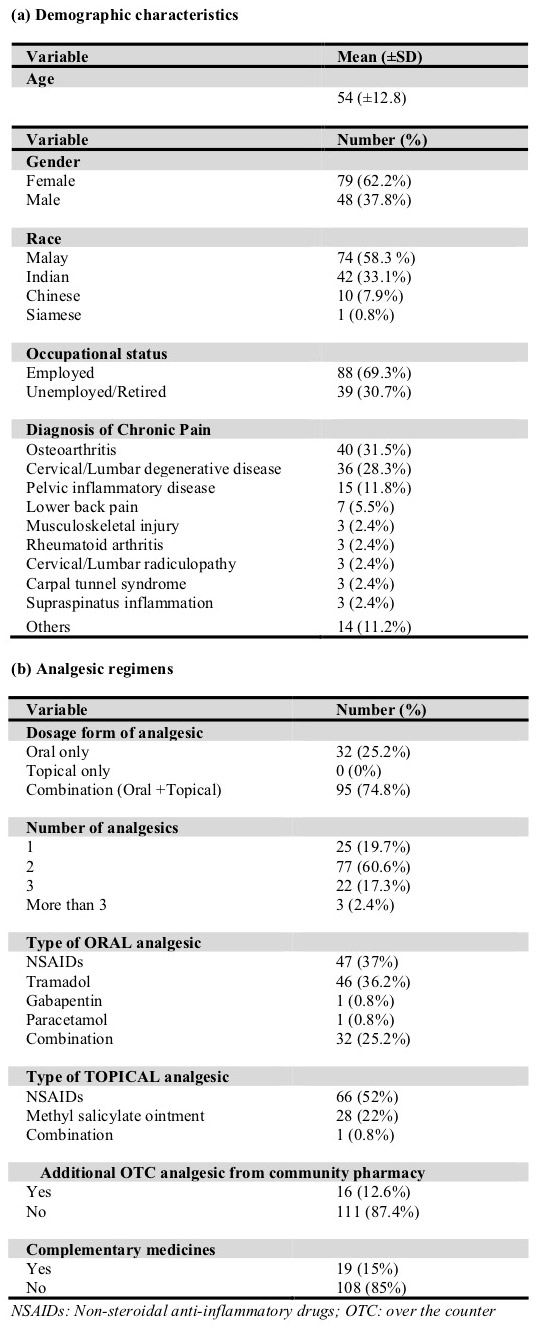

to participate in the survey due to time constraints. One hundred and twenty-seven (97.7%) outpatients with CNCP participated (b) in the study and were included in the final data analysis. Of these patients, forty-eight (37.8%) were male, and seventy-nine (62.2%) were female. The mean (± SD) age was 55 (±12.8) years. Majority of the patients were Malay (58.3%), followed by Indian (33.1%), Chinese (7.9%) and Siamese (0.8%). Most

of them were in full-time employment (68.5%), while 30.7% were unemployed at the time of the interview. As shown in Table I, the most frequent pain diagnosis was osteoarthritis (31.5%), followed by cervical or lumbar degenerative disease (28.3%) and pelvic inflammatory disease (11.8%). Pain diagnoses such as fibromyalgia, bone fracture, spinal stenosis, and anterior cruciate ligament injury were collectively grouped under the category of ‘others’ due to the relatively low frequency in our study subjects.

For pain management, most of the patients had been prescribed a combination of oral and topical analgesic (74.8%). Of note, a tremendous 80.3% of the patients needed at least two analgesics for pain control, and only 19.7% of them were treated with just an analgesic. NSAIDs, especially celecoxib and weak opioid tramadol, were the most frequent oral analgesics prescribed by our doctors, with a total combined frequency of 73.2%. On the other hand, topical NSAIDs (diclofenac and ketoprofen) were also the most frequently prescribed topical analgesic in our study subjects.

Table I: Baseline characteristics of study patients (N=127) (a) demographic data and (b) Analgesic regimen

In addition to medication supply from the hospital, 12.6% of patients bought OTC analgesics from a community pharmacy to supplement their prescription medicines, and nineteen (15%) patients practiced traditional and complementary medicines such as massage, acupuncture, meditation, and cupping as part of their pain management.

Pain Assessment

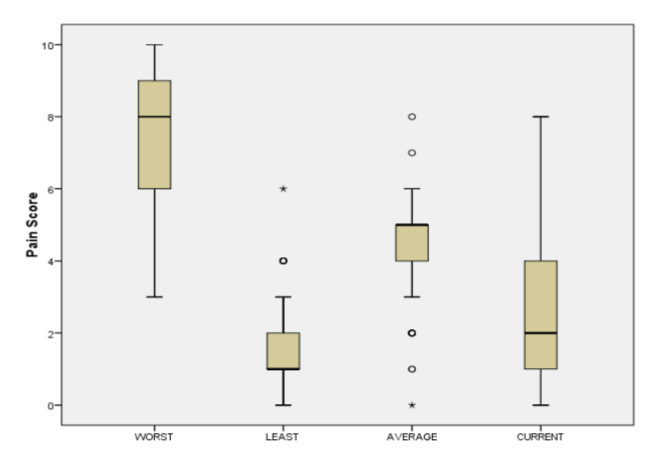

On average, patients reported their worst pain score at eight out of ten, while the least pain score was one out of ten (Fig. 1). The median percentage of pain relief from the prescribed analgesic(s) was seventy percent. With regards to the location of pain, 33.9% of patients experienced pain at more than one body part, 31.5% at trunk regions, 29.9% at lower limb(s), and only 4.7% at upper limb(s).

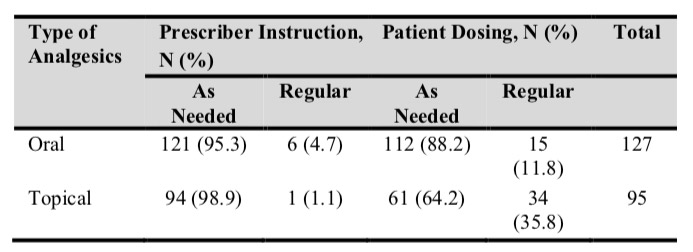

Prevalence of Different Analgesic Dosing Behaviors

An analysis of the prescribing pattern for oral analgesics showed that 95.3% of prescribers annotated ‘as needed’ dosing. Meanwhile, 88.2% of patients took their oral analgesic(s) ‘as needed’. (Table II) The study showed cases of discrepancy between the prescribed dose and the actual dose taken, but the frequency was minimal. For oral analgesics, only fifteen (11.8%) patients did not take their analgesic according to the prescribed instruction. Meanwhile, about one-third (34.7%) of patients applied topical analgesics regularly despite being instructed to apply only ‘as needed’ (Table II). We also discovered an alarming 98.4% of patients did not know the maximum allowable daily dose of the analgesic(s) prescribed to them when instructed to take as needed.

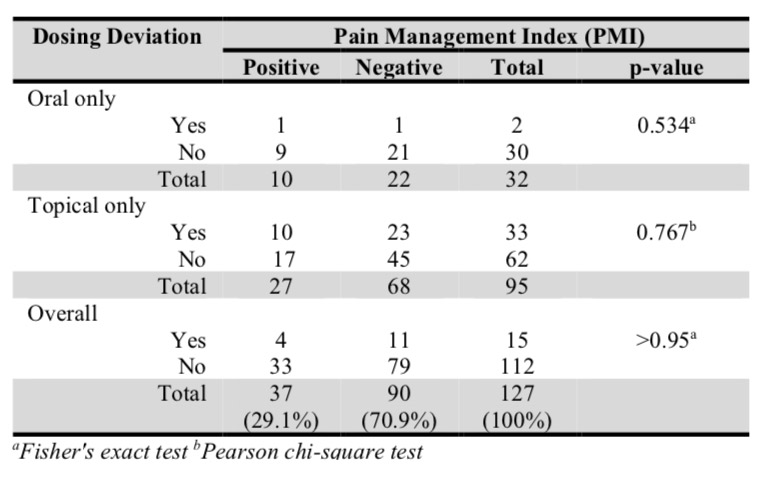

PMI and Pain Control

Our study demonstrated that as high as 70.9% of patients were under-treated for their chronic pain, represented by negative PMI as shown in Table III. No significant relationship was found between the dosing deviation with PMI; whether taking it via oral analgesics (p=0.534), topical analgesics (p=0.767), or the combination routes (p>0.95) (Table III).

Discussion

From this study, we observed a discrepancy in analgesic use between the prescribed dose and the actual dose taken by patients. There were 11.8% and 34.7% of patients who did not follow their prescriber’s instruction when using oral and topical analgesics. Earlier results of a qualitative study in 2006 also proved the existence of self-dosing behavior in analgesic use [22].

Regardless, the self-dosing behavior especially in the consumption of oral analgesics was not apparent in our study. 88.2% of patients took oral analgesic(s) ‘as needed’, which aligned with 95.3% of the ‘as needed’ prescribed instruction. However, the matching preference of both prescribers and the patients in our study subjects was far from good news. Current recommendations advocated regular administration of analgesics in chronic pain management [9,11-14], but only 4.7% of the prescriptions were written for ‘regular dosing’,

highlighting a guideline non-adherence in chronic pain management among our healthcare professionals.

Pain control was not found to be significantly associated with dosing deviation (p>0.95). Negative PMI, an indication of poor pain control with analgesics, was the major observation in our patients, regardless of whether they followed or deviated from the prescribed dose. Hence, additional analgesic should be added to the existing regimen for better pain control. In the study, none of the patients was prescribed a strong opioid, despite the fact that a few patients reported their worst pain score at 10, the highest pain score. In Kuala Lipis Hospital, strong opioids are reserved for cancer patients. Thus, the strongest analgesic available for CNCP patients in our setting is weak opioids. The prescribing practice will need to be reviewed following the results of the study, as the majority of CNCP patients in our study subjects were inadequately treated. Strong opioids should be used to manage severe pain, based on the WHO analgesic ladder [10] and local guidelines [23].

The most frequently prescribed oral analgesics in our setting were celecoxib and tramadol. Other oral analgesics that were prescribed to our patients were paracetamol and diclofenac. Gabapentin and pregabalin were also used as adjuvants in neuropathic pain. There were no prescribing records found for strong opioids in the management of CNCP. Celecoxib, a selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor, was the most commonly prescribed analgesic within the family of NSAIDs due to its better gastrointestinal safety profile. It was also well-accepted among doctors in Malaysia due to the general belief that celecoxib is more efficacious than conventional NSAIDs in reducing pain and inflammation [24]. On the other hand, the only weak opioids in our hospital formulary are tramadol and dihydrocodeine. Since dihydrocodeine is classified as a dangerous drug and hence more stringent prescribing criteria, the cheap and easily accessible tramadol is a popular add-on option for CNCP patients whose pain is uncontrolled with NSAIDs and paracetamol.

It was shown in our study that 98% of CNCP patients did not know the maximum allowable daily dose of analgesic(s) which they were taking. They claimed to take their analgesic(s) as needed without knowing the maximum allowable quantity per day. This situation is alarming as it can increase the risk of medication misuse and accidental overdose. In fact, an Australian report on injury research and statistics revealed that paracetamol, a type of analgesic, was accountable for the 2nd highest pharmaceutical poisoning cases (11%, n=718) [25]. Not only that, but the deficiency in patient knowledge about paracetamol use was also highlighted in a few descriptive and cross-sectional studies [26-28]. Therefore, the knowledge gap among patients on the safe use of analgesics could be an opportunity for pharmacists to play a bigger role in preventing cases of pharmaceutical poisoning. However, a hospital survey

on the counseling practice of pharmacists showed disappointing results. The survey confirmed that less than half of the pharmacists provided counseling and precautionary warnings when dispensing paracetamol [29]. Therefore, pharmacists need to do more in educating patients about the safe use of not just paracetamol but of all analgesics in pain management.

Besides the conventional analgesics, traditional and complementary medicines are gaining popularity and have become one of the popular alternatives in chronic pain management. It was found that 69.4% of the Malaysian population used traditional and complementary medicines throughout their life, and 55.6% of them used them annually [30]. In our study, nineteen (15%) patients sourced traditional and complementary medicines such as massage, acupuncture, meditation, and cupping; and reported efficacy from these alternatives. The positive experience with traditional and complementary medicines is also demonstrated overseas. In fact, a patient survey in Singapore found that as much as 72% of patients reported better pain relief with complementary medicines [31]. Gathering from the current evidence, traditional and complementary medicines can become an effective alternative approach in chronic pain management, especially among those patients who found limited pain relief from their current analgesics. However, they should be guided by informed healthcare professionals during the selection process so as not to fall victims to unscrupulous dealers, which eventually may give rise to other health complications.

Conclusion

The prevalence of ‘as needed’ dosing is higher than around-the- clock dosing in the management of chronic, non-cancer pain, with deviation from the prescribed instructions between 11.8- 34.7%. However, those differences were not significantly associated with the pain control. Our study highlighted that poor pain control in CNCP patients was due to fundamental error at the prescribing stage, starting from inappropriate analgesic choice and description of dosage frequency. Poor pain control was impacted less by patients deviating from prescribing instructions.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the Director-General of Health Malaysia for his permission to publish this article. We would also like to express our gratitude to Georgia Bolden-Strestik, Tan Jee Aik and Yap Pei Qi for helping to proofread the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Reference

- Merskey H, Bogduk N. Classification of chronic pain: descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms. 2nd ed. In: Merskey H, Bogduk N, editors. International Association for the Study of Pain. Seattle: IASP Press; 1994.

- Mohamed Zaki LR, Hairi NN. A systematic review of the prevalence and measurement of chronic pain in Asian adults. Pain ManagNurs. 2015;16(3): 440-52.

- Chronic pain declaration, Malaysian Association for the Study of Pain [cited 26th November 2019]. Available online from: http://www.masp.org.my/newsmaster.cfm?&menuid=14&action=ne ws&search=yes&searchtitle=&searchcategory=&queryname=news_t itle&sort_order=DESC

- Rudy TE, Kerns RD, Turk DC. Chronic pain and depression: toward a cognitive-behavioral mediation model. Pain. 1988;35(2):129-140.

- McWilliams L, Cox BJ, Enns MW. Mood and anxiety disorders associated with chronic pain: An examination in a nationally representative sample. Pain. 2003;106(1-2):127-133

- Wilson KG, Eriksson MY, D’Eon JL, et al. Major Depression and Insomnia in Chronic Pain. Clin J Pain. 2002;18(2):77-83.

- Cheung CW, Choo CY, Kim YC, et al. Collaborative efforts may improve chronic non-cancer pain management in Asia: Findings from a ten-country regional survey. J Pain Relief. 2015;05(01).

- Haefeli M, Elfering A. Pain assessment. Eur Spine J. 2006;15 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S17-S24.

- McKernan S. The pharmacological management of adults with chronic non-cancer pain, 2015 [cited 26th November 2019]. Available online from: http://www.lancsmmg.nhs.uk/wp- content/uploads/sites/3/2013/04/Chronic-Non-cancer-Pain- Guidelines-V1.1.pdf.

- WHO’s cancer pain ladder for adults. World Health Organization [cited 26th November 2019]. Available online from: https://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/painladder/en/

- Bwrddlechyd Aneurin Bevan Health Board. Analgesic ladder for primary care use. 2012 [cited 26th November 2019]. Available online from: http://www.wales.nhs.uk/sites3/Documents/814/PainLadder- ABHBNov2012.pdf

- Bruntsch U. Drug therapy of chronic pain: a practical approach. MMW Fortschr Med. 1999;141(42):30-2.

- Australia New South Wales Government. Chronic pain management: information for medical practitioners. 2018 [cited 26th November 2019]. Available online from: https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/pharmaceutical/doctors/Pages/chroni c-pain-medical-practitioners.aspx

- Morriss W, Goucke R. Essential pain management: workshop manual. 2ndedn. Melbourne: Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists; 2016.

- Awaluddin SM, Ahmad NA, Naidu BM, et al. Prevalence of non- steroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) use in Malaysian adults and associated factors: a population-based survey. Malaysian J. Public Health Med. 2017;17(3): 58-65

- Mittal P, Chan OY, Kanneppady SK, et al. Association between beliefs about medicines and self-medication with analgesics among patients with dental pain. PLoS ONE. 2018:13(8): e0201776.

- Epi Info, Version 7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2017. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/epiinfo/pc.html

- Cleeland C. The Brief Pain Inventory: user guide. The Brief Pain Inventory. 2009. Available online from: https://www.mdanderson.org/documents/Departments-and- Divisions/Symptom-Research/BPI_UserGuide.pdf

- Aisyaturridha A, Naing L, Nizar AJ. Validation of the Malay Brief Pain Inventory questionnaire to measure cancer pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006 Jan;31(1):13-21.

- Harminder S, Raja PSB, Baltej S. Assessment of adequacy of pain management and analgesic use in patients with advanced cancer using the brief pain inventory and pain management index calculation. J Glob Oncol. 2017;3(3): 235 – 41.

- Apolone G. Corli O, Caraceni A, et al. Pattern and quality of care of cancer pain management. Results from the Cancer Pain Outcome Research Study Group. Br J Cancer. 2009;100(10): 1566 – 74.

- Sale JEM, Gignac M, Hawker G. How “bad” does the pain have to be? A qualitative study examining adherence to pain medication in older adults with osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2006;55(2):272–8.

- Malaysian Association for the Study of Pain. A guide to the use of strong opioids in chronic non-cancer pain. 2015 [cited 26th November 2019]. Available online from: http://www.masp.org.my/index.cfm?menuid=33

- Chan HK, Bakri E, Tan SY, et al. Prescribing patterns of celecoxib and prescribers’ perceptions among three general hospitals in Northern Malaysia. Arch Pharma Pract. 2014;5(1): 28-34.

- Tovell A, McKenna K, Bradley C & Pointer S. Hospital separations due to injury and poisoning, Australia 2009–10. Injury research and statistics series no. 69. Cat. no. INJCAT 145. Canberra: AIHW.

- Hornsby LB, Whitley HP, Hester EK, et al. Survey of patient knowledge related to acetaminophen recognition, dosing, and toxicity. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2010;50(4):485-9.

- Shone LP, King JP, Doane C, et al. Misunderstanding and potential unintended misuse of acetaminophen among adolescents and young adults. J Health Commun. 2011;16(Suppl 3): 256–67.

- Wolf MS, King J, Jacobson K, et al. Risk of unintentional overdose with non-prescription acetaminophen products. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(12): 1587–93.

- Ali I, Khan AU, Khan J, et al. Survey of hospital pharmacists’ knowledge regarding acetaminophen dosing, toxicity, product recognition and counselling practices. J Pharm Health Serv Res. 2017;8(1):39–43.

- Siti ZM, Tahir A, Farah Al, et al. Use of traditional and complementary medicine in Malaysia: a baseline study. Complement Therapies in Med. 2009;17(5-6):292-9.

- Tan MG, Win MT, Khan SA. The use of complementary and alternative medicine in chronic pain patients in Singapore: a single- centre study. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2013;42(3):133-7.

Please cite this article as:

Mohamad Akmal Bin Harun, Nurul Fateeha Binti Ahmad and Cheah Huey Miin, Analgesic Dosing Behaviours in Patients with Chronic, Non- Cancer Pain: Does it Affect the Pain Control?. Malaysian Journal of Pharmacy (MJP). 2021;1(7):28-33. https://mjpharm.org/analgesic-dosing-behaviours-in-patients-with-chronic-non-cancer-pain-does-it-affect-the-pain-control/