Abstract

Background: Dual therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel is the standard treatment for acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Dual antiplatelet therapy plays an important role in reducing major acute, short- and long-term adverse clinical outcomes. Currently, the economic evaluation of ticagrelor, a reversible and direct-acting oral antagonist of adenosine diphosphate receptor P2Y12 remains unknown.

Objective: To compare the annual cost of ticagrelor versus branded clopidogrel in patients with ACS from a Malaysian health care perspective.

Methods: The data required for this analysis was obtained from a 2007 study carried out by Fong et al. in ACS patients (n=57). Assumptions used for the present analysis were based on data from the Cardiac Rehabilitation Program (CRP) study, the Study of Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes (PLATO) and the National Cardiovascular Disease ACS (NCVD ACS) registry of Malaysia. For all calculations, the Ringgit Malaysia (RM) currency and prices as of 2007 were considered.

Results: The cost of clopidogrel treatment in post-ACS patients for 30 days was calculated to be RM1,381,340 (n=2072; daily cost=RM5.50) and assuming treatment with ticagrelor, the cost would be RM1,554,000 (daily cost=RM8.70). Based on PLATO and NCVD ACS 2007, it was estimated that major adverse coronary event (MACE) in the form of unstable angina (UA) would occur in an additional 21 patients on clopidogrel, which could have been avoided with ticagrelor. Extrapolating cost data from CRP study, it was estimated that the annual costs for 21 additional cases of UA in terms of annual treatment and readmission would be more than RM400,000. Treatment with ticagrelor would thereby be associated with lesser number of MACE that can be translated in avoiding annual costs of treatment of UA and result in annual cost savings of RM238,856.

Conclusion: Although direct comparisons were not made, this analysis suggests that ticagrelor therapy may be a more cost-saving alternative to clopidogrel in Malaysian patients with ACS. Keywords: ticagrelor, clopidogrel, acute coronary syndrome, cost analysis, major adverse coronary event.

Introduction

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is an important cause of mortality and hospitalisation in Malaysia. It encompasses a range of ischaemic heart diseases, such as unstable angina (UA), non- ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) and ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). It most commonly occurs due to the rupture, fissuring or ulceration of an atherosclerotic plaque along with thrombosis and coronary vasospasm [1]. According to the National Cardiovascular Disease ACS (NCVD ACS) report 2007 and 2008, there were 2851 ACS-related admissions in Malaysia in 2008, of which 54% patients were admitted with STEMI, 23% with NSTEMI and 23% with UA. ACS was more common in males than females, with the former constituting 75% of the ACS-related admissions in 2008. The in-hospital mortality rate associated with ACS during the period from 2006 through 2008 was between 7% and 8% [2]. In GRACE study, the median age of ACS patients; with STEMI was 64 years, with NSTEMI was 68 years, and with UA was 66 years. However, in Malaysia according to NCVD ACS report for 2006, 2007, and 2008 the median age of ACS patients with STEMI, NSTEMI and with UA were same at 59 years suggesting that people are getting affected with ACS at an younger age when compared to developed countries. Hence, it is necessary to study different treatment patterns along with associated cost to develop cost analysis strategies for patients of different socioeconomic backgrounds in Malaysia [3].

Acute coronary syndrome is characterised by partial or complete blockage of epicardial coronary artery, which occurs due to a platelet-rich thrombus. Since the prognosis of the condition depends on the activity of platelets, dual antiplatelet therapy is considered necessary to avoid a repeat occlusion in the target vessel after a successful percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Until recently, aspirin and clopidogrel were the drugs forming the dual antiplatelet therapy. The antiplatelet activity of clopidogrel is dependent on the formation of the active metabolite from the prodrug. Various genetic or non-genetic factors influence this bioactivation, which takes place in two metabolic reactions in the liver. As a result, clopidogrel is associated with considerable interindividual variation in antiplatelet activity. Delayed and/or insufficient bioactivation causes low- or no-response, thereby leading to adverse cardiovascular outcomes, such as stent thrombosis, recurrent MI, or cardiovascular death [4]. The limitations associated with clopidogrel therapy have opened avenues for new antiplatelet agents.

Ticagrelor, an oral and reversible inhibitor of the P2Y12 receptor, belongs to a novel chemical class called cyclopentyl-triazolopyrimidine [5]. It is a direct acting agent and has a quicker and more predictable onset of action compared with clopidogrel [4][5]. Also, the more rapid neutralisation of ticagrelor’s effect allows platelets to resume function more quickly [5].

The Study of Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes (PLATO) was a multicentre, randomised, double-blind trial conducted in 18,624 patients to assess the superiority of ticagrelor over clopidogrel in the prevention of vascular events and death in patients who had ACS with or without ST elevation. This study demonstrated that treatment with ticagrelor was associated with a significant reduction in mortality from vascular causes, myocardial infarction, or stroke as compared with clopidogrel without an increase in the rate of overall major bleeding. However, an increase in the rate of non-procedure-related bleeding was noted with ticagrelor. Based on the PLATO trial, several subgroup analyses were conducted to evaluate the efficacy of ticagrelor in various patient populations. These analyses demonstrated beneficial effects of ticagrelor over clopidogrel in patients with STEMI referred for primary PCI, patients with diabetes, patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft, and patients with chronic kidney disease. These results provided evidence for inclusion of ticagrelor in European Society of Cardiology guidelines for ACS without ST elevation and myocardial revascularisation [6].

Economic analyses from the PLATO trial and other studies that compared ticagrelor with clopidogrel in patients with ACS, have suggested that ticagrelor therapy may be more cost- effective than clopidogrel [7][8][9][10].

The present study was conducted to assess the cost savings of treatment with ticagrelor for 30 days in Malaysian patients with ACS. This study seeks to supplement expert opinion with empirical data regarding the next potential alternative for antiplatelet therapy in ACS.

Methods

The study had recruited consecutive patients admitted with ACS at Cardiac Tertiary Referral Centre (CTRC), Sarawak General Hospital, Malaysia (n=57), which is currently known as Sarawak General Hospital Heart Centre and at District General Hospital Sibu, Malaysia (n=32) from 1 October 2007 to 30 November 2007. All patients attended routine pre-scheduled outpatient follow-up 30-days after hospital discharge. For the purpose of this analysis, baseline characteristics and patient outcomes at 30 days were retrieved from this study.

Analysis of Cost Saving

The cost details captured for this analysis included costs of all medical and non-medical supplies and costs incurred from the perspective of the healthcare provider. For the purpose of this study, it was assumed that reducing the number of events (non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke, severe recurrent ischaemia, UA or other vascular causes) will ultimately reduce the overall cost of treatment.

The incurred cost in treatment of a disease possibly indicates the disease burden and can be measured descriptively through a cost of illness study, which translates the entire burden of resources used in the treatment into a monetary value. Measuring the direct costs during hospitalisation and discharge would be the most ideal approach to identify direct economic burden to health care providers over a period of time. Based on the data obtained from Cardiac Rehabilitation Program (CRP) study, the rate of hospitalisation resulting from ACS was estimated [11]. The direct medical costs were calculated by multiplying the number of interventions (drug doses, laboratory tests, procedures, consumables, medical equipments, and other investigations) with the cost per intervention. This direct medical cost correlates with the number of interventions necessitating hospital stay, clinical examination and also on the length of stay with each event of hospitalisation.

Several simplifying assumptions are made to maintain transparency in the model structure. Post- ACS, a patient may be indicated for coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), elective surgery for PCI or medications. Prices as of 2007 are considered for calculations and the currency is Ringgit Malaysia (RM). The economic evaluations are done to compare the two-treatment strategies between those patients with clopidogrel and to those patients who could have been opted to ticagrelor as an alternative ADP inhibitor. The projected potential cost savings for treatments and expected health outcomes of MACE are obtained by comparing the two treatments option. All data used are based on a single clinical trial at Cardiac Tertiary Referral Centre and NCVD database, which are applied to compare the cost and consequences of treatments. Probability of switching to ticagrelor in cost evaluation strategies would help to estimate the exact cost saving in interventions and treatment options particularly in long-term disease management.

Because a range of cost of treatments for ACS was used, there is inevitably some uncertainty in estimated costs incurred for interventions. Sensitivity analysis was therefore conducted. The effect of treatment of MACE, cost of interventions, total cost treatment and other key data in costs of managing ACS were tested.

Results

For this analysis, data related to patients recruited only at CTRC Sarawak was considered as cost details were available only for this hospital. The baseline characteristics of these patients as collected in the study by Fong et al. have been outlined in Table 1 [12].

This study provided information on the occurrence rate of major adverse coronary events (MACE) during the first 30 days post ACS. In this study that based on our local setting, we extracted and applied relevant information on cardiovascular death rate and UA incidences unto NCVD ACS database. Among the 57 patients recruited, 7 had a MACE; of which, 4 were cardiovascular deaths and 3 were UA (Table 2). This fraction 4 over 7 (4/7 MACE) can be related to a similar approach presented in NCVD ACS where cardiovascular death rate was 10%. Similarly, UA was seen in a fraction of 3 over 7 MACE or corresponding rate 7.5% MACE in ACS patients post admission in 30 days. Thus, the prevalence rate of total MACE as estimated from NCVD ACS 2007 was 17.5% [12].

From the NCVD-ACS report 2007 and 2008, it was extrapolated that 65% of all patients with ACS who were admitted for treatment, received a daily maintenance dose of an adenosine diphosphate (ADP) antagonist with or without a loading dose [2]. It was assumed that the ADP antagonist given to patients was clopidogrel as during that period the evidence recommended clopidogrel and it was also the only standard drug available [13][14].

According to the NCVD ACS registry, there were 3,646 cases of ACS in 2007 (2). Of these patients, 2,072 fulfilled the inclusion criteria used in the PLATO study and were used for all cost calculations in this analysis. The daily cost of ticagrelor was higher compared with clopidogrel (RM8.70 vs. RM5.50, respectively). The 30-day drug cost of clopidogrel treatment in Malaysian patients with ACS was calculated to be RM1,381,340. Using the same pool of patients and assuming that ticagrelor was used instead of clopidogrel, the corresponding costs of treatment with ticagrelor would be RM1,554,000. The difference in the costs of the two treatments would be RM172,660 higher for ticagrelor.

The PLATO study demonstrated that there was a relative risk reduction (RRR) of 12.2% in the primary event, favouring the ticagrelor arm at 30 days. The estimated MACE from NCVD ACS 2007 was 17.5% and the rate of MACE could have been reduced to 15.4% if all the ACS population in 2007 were treated with ticagrelor. Based on this information, it is estimated that 158 patients were having MACE when using clopidogrel and only 137 MACE when using ticagrelor.

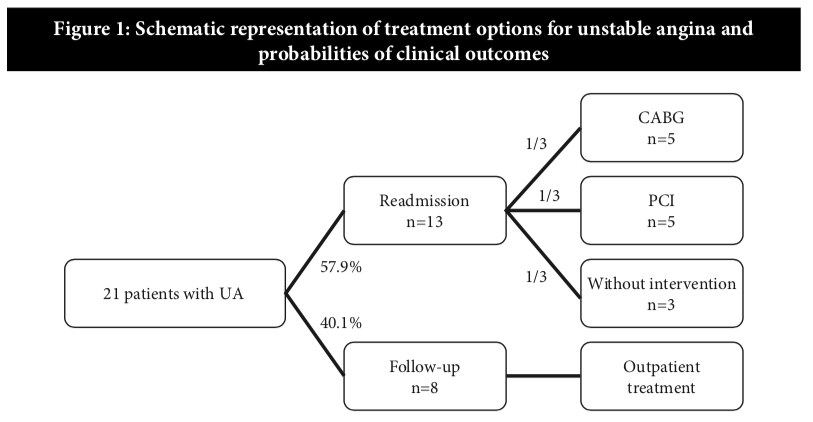

Thus, there were 21 additional cases of readmission due to UA with clopidogrel treatment (Figure 1).

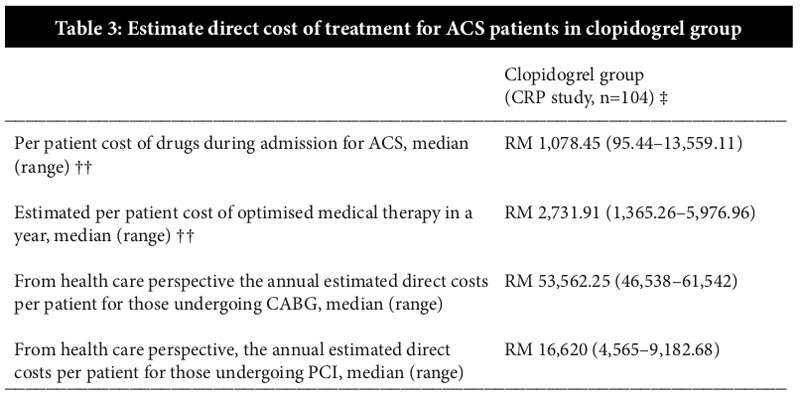

To calculate the costs of readmission and management of 21 patients with UA, data from CRP study was used. According to CRP study (11), the total direct cost for patients undergoing CABG during the subsequent 12-month follow-up period was estimated to be a median value of RM53,562 and the cost for patients on inpatient coronary angiography during the subsequent 12-month follow-up period was a median value of RM16,620 which was three times less than patients who had undergone CABG (15). Activity based costing (ABC) method was used to determine the direct cost including consumables, medications and all other operational costs associated with treatment. However, indirect cost was not considered to determine the cost for treatment. (Table 3)

‡ Drug prices based on 2007 market pricing.

†† Cost of pharmaceutical expenditure during admission for quasi-experimental design in CRP study (n=104). Only clopidogrel (Plavix®) was available and indicated for this ACS group.

Translating the findings from the study by Fong et al., of the 21 patients readmitted with UA, as high as 57.9% (13 patients) would be planned for or underwent PCI or CABG within 30 days. It was assumed that an approximately equal number would undergo PCI with drug eluting stent (1/3×13 ≈ 5 PCI procedures), and CABG (1/3×13 ≈ 5 CABG) and the rest would be on optimal medical therapy alone. Therefore, the estimated annual costs for 21 cases of UA in terms of re-admissions and treatment would cost the health care provider more than RM400,000. Although the daily cost of ticagrelor treatment is higher, it is associated with lesser number of readmissions when compared with clopidogrel, thereby resulting in annual cost savings of RM238,856 (Table 4).

‡ Drug prices based on 2007 market pricing.

† The average medical cost per patient for ACS in first 30 days treatment with clopidogrel was $194.36 ($1= RM3.43).

* Approximately higher numbers of patients undergo medical therapy, but equal numbers undergo PCI and CABG.

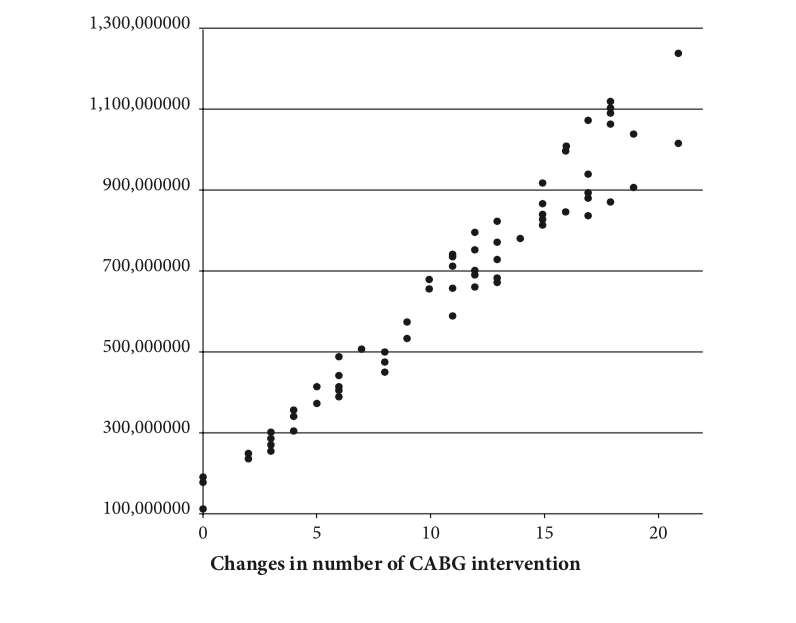

One-way sensitivity analyses were performed by changing estimated costs within a range of potentially reasonable values all treatment options (CABG, PCI or medication alone) and evaluating whether changes in treatment options of 21 patients with UA modify incurred cost. If total CABG intervention at that year escalates, the total incurred cost of treatment will definitely increase. It can be clearly seen that the overwhelming majority of simulation results are located above of RM400,000. The maximum estimated total incurred cost of treatments could reach to RM1.2 million. The analysis showed that even if we decrease the number of major intervention like CABG, it would not extensively decrease the cost of treatments of MACE. This reflects the significance of using ticagrelor and suggests a high probability of cost avoidance in the treatment of MACE (Figure 2).

Discussion

Acute coronary syndrome, which was initially associated with developed countries, is on the rise in Asia-Pacific countries, including Malaysia [16][17]. In order to reduce the risk of developing ACS and control the associated burden, a comprehensive action plan is required. To this end, the NCVD ACS registry was established in 2006, to capture data of ACS patients in Malaysia [17]. According to the NCVD ACS report 2007 and 2008, ACS is affecting the Malaysian population at a much younger age (<50 years) when compared with findings from GRACE. During the period from 2006 through 2008, ACS was associated with in-hospital mortality rates between 7% and 8% [2].

The availability of newer therapies has provided more alternatives to treating physicians. However, physicians must be armed with sufficient knowledge regarding new drugs in order to ensure their optimal usage. This includes not only clinical data regarding the efficacy and safety of the drug, but also data on its cost-effectiveness. This helps in efficient utilisation of the limited health care resources available [18].

Cost analyses based on the PLATO trial have been conducted to determine the cost-effectiveness of 12-month ticagrelor treatment in patients with ACS as compared with clopidogrel [7][8]. In one such analysis conducted by Nikolic et al., ticagrelor treatment was associated with a quality- adjusted life years (QALYs) gain of 0.13 and increased costs of €362, yielding a cost per QALY gained of €2753 as compared to generic clopidogrel. The cost per life year gained was €2372. The price of generic clopidogrel considered was €0.06 per day (lowest available price as of July 2011) and that of ticagrelor was €2.21 per day (reimbursed price in Sweden). The cost analysis of ticagrelor was uniform across all subgroups of ACS patients—those with UA, STEMI, NSTEMI, and those planned for invasive management. The study concluded that the cost per QALY gained with ticagrelor treatment in patients with ACS for a 12-month period is within the usually accepted levels for cost-effectiveness [8]. Another analysis based on the PLATO trial published previously had shown similar results. The price considered for clopidogrel and ticagrelor for this study was €0.17 per day and €2.25–3.50 per day, respectively [7].

The absence of similar data for countries in Asia, prompted Chin et al. performed a cost- effectiveness analysis of ticagrelor treatment in patients with ACS in Singapore. This study was based on data obtained from the PLATO trial. The daily cost of clopidogrel and ticagrelor considered was 1.05 and 6.00 Singapore Dollar ($), respectively. The QALY gained with ticagrelor was 0.13 at a lifetime incremental cost of $1328, yielding a cost per QALY of $10,136. The study demonstrated that even after considering the low willingness-to-pay threshold in Singapore according to World Health Organisation standards, 12-month treatment with ticagrelor in patients with ACS is likely to be favorable. The lower hospitalisation-related costs with ticagrelor, mainly lower bed-days and lesser interventions, compensate partly for the higher drug cost of ticagrelor [18].

These results are similar to the results obtained in our study. Our study also demonstrates that in Malaysia, treatment with ticagrelor can result in annual cost savings of RM238,856 when compared with clopidogrel. Although there are short-term cost savings with clopidogrel, the trend clearly shows that readmission rates are higher, thereby increasing the overall cost of treatment and cost burden in managing patients in acute setting.

To our knowledge, this cost analysis is the first of its kind to evaluate the cost of ticagrelor compared with clopidogrel in Malaysian patients with ACS. It was carried out to supplement the clinical data on ticagrelor use in Malaysia. It was based on treatment outcomes of ticagrelor from the PLATO trial, prevalence of ACS in Malaysia from NCVD ACS registry and treatment outcomes of clopidogrel in Malaysian patients from a 2-month study in CTRC Sarawak. We hope that this study will provide a basis for future studies that will estimate the cost saving of ticagrelor by its actual use in Malaysian patients with ACS. Such studies will help guide hospitals and physicians to make informed decisions regarding the usage of ticagrelor in patients with ACS.

Limitation

This study has certain limitations. It is limited to a single centre; however, the results are likely to be relevant to cardiac centres outside the state also in terms of intended management strategy (i.e., medical, interventional, or surgical) and clinical events [19][20]. Certain assumptions, which were made for this study, may affect the robustness of results. Also, clinical outcomes of ticagrelor treatment were adapted from the PLATO study and extrapolated to the Malaysian population. This may again affect the results of our analysis as treatment outcomes may vary in different populations.

It is also likely that the incurred costs for treatments and interventions for ACS were underestimated in this analysis as only the perspective of the healthcare providers’ was considered. A complete overview of the cost of ticagrelor treatment in patients with ACS could have been obtained, only if we could measure the costs incurred from the societal perspective. In addition, data for this analysis was retrieved from two clinical studies conducted at our local setting and the costs per survivor for post-ACS participants were estimated manually from the anticipated records as the case note, prescription profile, laboratory investigation, and other relevant documents. The cost of branded clopidogrel was considered for this analysis because only the branded drug was available in Malaysia in the year 2007. This might have implications on the cost savings derived from ticagrelor treatment in this analysis.

Conclusion

In this analysis, a formal link was established between measures of costs and outcomes of ticagrelor therapy, although direct comparisons cannot be made. This economic analysis suggests that ticagrelor therapy may be a more cost-saving alternative to clopidogrel in Malaysian patients with ACS. However, a head-to-head comparison in larger population may be required to further validate the findings of this study.

Acknowledgements

Our appreciation and thanks to the Director-General of Health Malaysia, for permission to share and publish these findings. We are grateful to Dr Maggie Seldon, Tiong Lee Len and Lana Lai for providing support for the cost details used in the study and to all individuals who supplied pricing information.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Azman WA, Sim KH, et al. Annual Report of the NCVD-ACS Registry Malaysia 2006. National Cardiovascular Disease Database (NCVD). Available at: http://www.acrm. org.my/ncvd/documents/1stAnnualReport/20081013_ncvdACSReport.pdf. Accessed on: December 16, 2013.

- Azman WA, Sim KH, et al. Annual Report of the NCVD-ACS Registry Malaysia 2007 & 2008. National Cardiovascular Disease Database (NCVD). Available at: http://www.acrm.org.my/ncvd/documents/report/acsReport_07-08/fullReport.pdf. Accessed on: December 16, 2013.

- Steg PG, Goldberg RJ, Gore JM, et al,. Baseline characteristics, management practices, and in-hospital outcomes of patients hospitalized with acute coronary syndromes in the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE). Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:358–363.

- Höchtl T, Sinnaeve PR, Adriaenssens T, et al. Oral antiplatelet therapy in acute coronary syndromes: update 2012. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2012;1:79–86.

- RoffiM,PatronoC, ColletJP,etal.ESCGuidelinesforthemanagementofacutecoronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2015 Available at: http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/ehj/early/2015/08/28/eurheartj.ehv320.full.pdf Accessed on: September 13, 2015.

- Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1045–1057

- Henriksson M, Nikolic E, Janzon M, et al. PCV46 Long-term costs and health outcomes of treating acute coronary syndrome patients with ticagrelor based on the EU label: cost- effectiveness analysis based on the PLATO study. Value Health. 2011;14:A40.

- Nikolic E, Janzon M, Hauch O, et al. Cost-effectiveness of treating acute coronary syndrome patients with ticagrelor for 12 months: results from the PLATO study. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:220–228.

- Theidel U, Asseburg C, Giannitsis E, et al. Cost-effectiveness of ticagrelor versus clopidogrel for the prevention of atherothrombotic events in adult patients with acute coronary syndrome in Germany. Clin Res Cardiol. 2013;102:447–458.

- Crespin DJ, Federspiel JJ, Biddle AK, et al. Ticagrelor versus genotype-driven antiplatelet therapy for secondary prevention after acute coronary syndrome: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Value Health. 2011;14:483–491.

- Anchah L, Sim KH, Izham M, et al. The economic and humanistic outcomes of post acute coronary syndrome in cardiac rehabilitation program: A quasi-experimental design of 12 months follow-up. National Heart Association of Malaysia. Available

at: www.e-mjm.org/2010/v65n3/National_Heart_Association_Abstracts.pdf. Accessed on: December 16, 2013. - Fong AYY, Tiong LL, Wong JL, et al. Impact of an onsite cardiac catheter laboratory and pharmacotherapy on clinical outcomes of Acute Coronary Syndrome: A comparison of a Tertiary Referral Centre with a District General Hospital. Available at: http://www.malaysianheart.org/files/151303501049f02201533ae.pdf. Accessed on: December 16, 2013.

- Hayasaka M, Takahashi Y, Nishida Y, et al. Comparative effect of clopidogrel plus aspirin and aspirin monotherapy on hematological parameters using propensity score matching. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2013;9:65–70.

- Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR et al. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:494–502.

- Anchah L, Izham M, Sim KH, et al. Cost-utility analysis of the modified cardiac rehabilitation program: A preference-based on SF-6D. MPS Pharmacy Scientific Conference 2011. Malaysian J Pharmacy. 2011;1(9).

- Chin SP, Jeyaindran S, Azhari R, et al. Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS) Registry – Leading the Charge for National Cardiovascular Disease (NCVD) Database. Med J Malaysia. 2008;63(Suppl C):29–36.

- Lu HT, Nordin RB. Ethnic differences in the occurrence of acute coronary syndrome: results of the Malaysian National Cardiovascular Disease (NCVD) Database Registry (March 2006 – February 2010). BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2013;13:97.

- Chin CT, Mellstrom C, Chua TS, et al. Lifetime cost-effectiveness analysis of ticagrelor in patients with acute coronary syndromes based on the PLATO trial: A Singapore Healthcare Perspective. Singapore Med J. 2013;54:169–175.

- Hill SR, Mitchell AS, Henry DA. Problems with the interpretation of pharmacoeconomic analyses: A review of submissions to the Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. JAMA. 2000;283:2116–2121.

- Bainey KR, Norris CM, Gupta M. Altered health status and quality of life in South Asians with coronary artery disease. Am Heart J. 2011;162:501–516.

Please cite this article as:

L Anchah, AYY Fong and TK Ong, Cost Analysis on Ticagrelor Utilisation in the Treatment of Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Preliminary Study. Malaysian Journal of Pharmacy (MJP). 2015;1(2):1-11. https://mjpharm.org/cost-analysis-on-ticagrelor-utilisation-in-the-treatment-of-patients-with-acute-coronary-syndrome-a-preliminary-study/