Abstract

Tablet splitting practices have been shown to reduce the medication cost in many countries. This study was aimed to evaluate the tablet splitting practices among community pharmacists in Penang, Malaysia. A two-month cross-sectional descriptive survey was carried out in forty randomly chosen community pharmacies in Penang. The pharmacists were required to document all their tablet splitting recommendations during the study period. The data collected includes the appropriateness of the tablet splitting recommendations by pharmacists; the extent of communication between pharmacists and physicians when recommending tablet splitting; the physicians‟ and patients‟ acceptance towards the tablet splitting; and the documentation of cost-saving achieved from the tablet splitting. The result showed that the tablet splitting was recommended by 31.0% of the pharmacists who receives prescriptions eligible for this practice. Tablets of patent- protected innovator brands were more likely to be recommended for splitting. Majority (92.9%) of the splitting recommendations were appropriate except two cases which involve unscored combination tablet. The pharmacists requested consent from the physicians for 42.9% of the splitting recommendations and majority (91.7%) of the requests were accepted. Meanwhile, the patients‟ acceptance rate for splitting recommendation was 82.1%. Through acceptance of tablet-splitting, the patients‟ monthly expenses on drugs reduced by 36.5% and this correspond to a monthly saving of RM39.05 (US$10.30, US$1.00 = RM 3.80) per patient. The study concluded that the tablet splitting is not a common practice among the community pharmacists, however both the physicians and patients highly accept pharmacists‟ suggestion on splitting. The findings also revealed that tablet splitting can be used as a cost-containment measure for patient as well.

Introduction

Recently, increase in countries‟ expenditures on prescription drugs has become a worldwide dilemma. In Malaysia, the government fully subsidizes the drugs expenditure in public hospital. However, the government subsidized cost for drugs in public hospital increased from RM 200 million in 1995 to RM 800 million in 2005 with an annual increment of 10%- 15%, thus this had affected the government‟s ability to sustain pharmaceutical financing in the future [1][2]. Besides, 56% of Malaysian consumers perceived drugs in private sector as expensive and 68% urged that prices should be reduced [3]. The high drugs cost may generate prescription non-compliance and thus in return will further increase healthcare costs [4].

Many studies highlighted that tablet splitting resulted in significant cost- saving [5][6][7][8][9][10]. For instance, introduction of tablet splitting by a health plan in North Caroline generated annual savings of US$342,000 [5]. However, tablet splitting is contraindicated for extended release formulation and enteric-coated tablet [11][12][13][14]. Unscored tablet and combination tablet are generally not mean to be split, but some tablets without scoring may be split easily with tablet-splitting device [11][12]. Unacceptable weight variation can be resulted from tablet splitting and may be clinical significant for narrow therapeutic drug [15][16][17]. Therefore, this practice only suitable for drugs with wide therapeutic range and long half life [7][12][14][15][16][17][18]. Previous studies had shown that majority of the patients‟ compliance was not hindered after introduction of tablet splitting [19][20][21]. Nevertheless, tablet splitting is not suitable for cognitively and functionally impaired patients who could lead to confusion and incorrect dosing [13][14].

In the current context of pharmacy practice in Malaysia, there is no dispensing separation policy been implemented between private general practitioners and community pharmacists. There is also no tablet- splitting guideline for health professionals in Malaysia. Under these circumstances, little is known about the pharmacist‟s tablet splitting practices and the response of physician and patient toward the splitting recommendation.

Aim of the study

This study aims to document the tablet splitting practices among Malaysian community pharmacists with the focus on the appropriateness of the tablet splitting recommendations; the extent of communication between pharmacists and physicians while recommending tablet splitting; the physicians‟ and patients‟ acceptance towards the tablet splitting; and the cost-saving resulted from the tablet splitting practices.

Method

This is a cross-sectional descriptive survey study using a self-completed data form for pharmacists to fill in. This data form was modified from the data collection form obtained from previous study undertaken in Scotland [22]. This data form has been tested for face and content validity by five pharmacy academics and 10 pharmacists. The sample of the form is shown in Appendix 1.

The population of community pharmacists in Penang state was stratified into urban and rural area. The sampling frame was the pharmacies list provided by State Pharmacy Enforcement Department. Thirty and ten outlets were randomly chosen from the urban and rural area respectively and resulted in total of 40 community pharmacies as the sample.

This study includes patients who brought prescriptions written in branded or generic name to the community pharmacies. These drugs are available in various strengths which are eligible for tablet splitting. The pharmacists were requested to document their tablet splitting recommendation to the patient, including the brand name of the drug involved, the strength, the dosage regimen, the cost and selling price of the drug, the decision either to consult or not consult the physician with regards to splitting recommendations, and physician and patient‟s acceptance toward the recommendation made. Patients who have a risk that tablet splitting will impair their understanding and compliance to therapy were excluded from the study.

The researcher sent the data form by personal visit to the selected outlets and detail explanations was given to the pharmacists. The participation of this study was strictly voluntary and no personal data of the participants were reported. The duration of data collection was 2 months period from 22nd February 2005 to 22nd April 2005. Follow-up and data collection were done by monthly personal visit by the researcher. All the collected data was entered into SPSS® version 11.5 for analysis.

Results

From the chosen sample of forty pharmacies (one pharmacist in each outlet), 34 pharmacists (85.0%) agreed to participate in this study. At the end of the study, only 9 (26.5%) pharmacists involved in tablet-splitting practices. Five pharmacists (14.7%) did not receive any prescription eligible for tablet splitting. The remaining 20 pharmacists (58.8%) did not recommend tablet splitting although they have the opportunity to do so. In another words, among the 29 pharmacists which received prescriptions eligible for tablet splitting, only 31.0% (9 pharmacists) recommended tablet splitting to their patients.

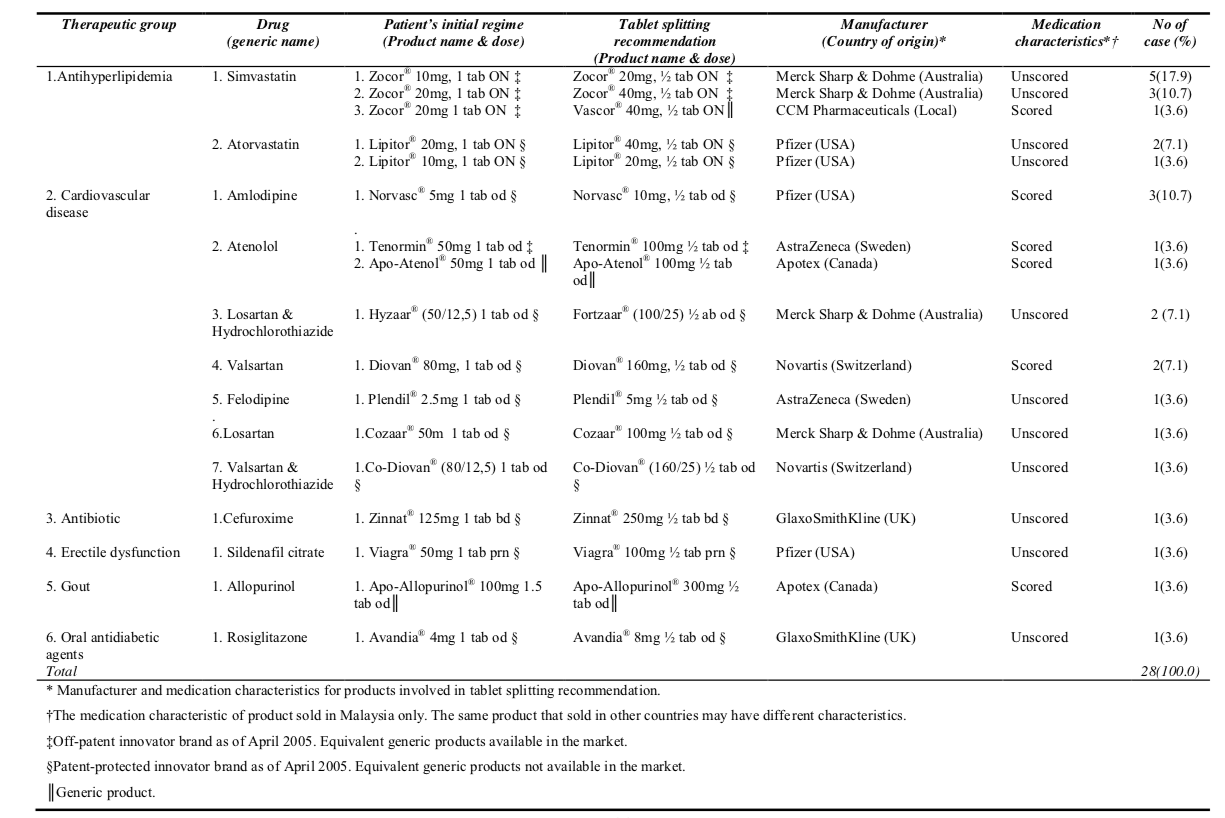

Total numbers of patients involved in tablet splitting recommendation were 28. There were 28 items involved and one item was considered as one case of tablet splitting recommendation. Besides, the cases involved 13 drugs and 17 products with different strength (Table 1).

Analysis of tablet splitting practices

Majority of the cases involved antihyperlipidemia (42.8%) and cardiovascular drugs (42.8%), followed by antibiotic (3.6%), erectile dysfunction (3.6%), gout (3.6%) and diabetic mellitus (3.6%). Almost all (96.4%) of the cases involved Class B Poison which under the Malaysian Poison Law 1952 can only be sold with a prescription from a registered medical, dental or veterinary practitioners. Only one case (3.6%) involved Class C Poison which under the Malaysian Poison Law can be sold without a prescription by a registered pharmacist in a registered pharmacy premise.

Among the tablet splitting recommendations, 57.2% involved patent-protected innovator brands, followed by 32.2% of off-patent innovator brands which equivalent generic products were available as of the date of this research. Only 10.6% of the cases involved generic products. Zocor® (Simvastatin) was the most popular drug involved in tablet splitting recommendation which consist of 28.6% of the cases and followed by Lipitor® (Atorvastatin) (10.7%) and Norvasc® (Amlodipine) (10.7%) (Table 1).

Detail analysis noticed one unique case of generic substitution occurred concurrently with tablet splitting. In this case, the patient accepted to change the therapy from Zocor® (Simvastatin) 20mg, one tablet daily to Vascor® (manufactured by CCM Pharmaceuticals, a local generic company) 40mg half tablet daily (Table 1). This unique case saved RM62.55 (US$16.50) per month (28 days) for the patient with RM47.60 (US$12.55) of the cost-saving was gained from the generic substitution (Zocor® 20mg, 28 tablets

cost RM93.35; Zocor® 40mg, 14 tablets cost RM78.40; Vascor® 40mg, 14 tablets cost RM30.80; RM3.80 = US$1.00). There was another unique case involved simplified the patient‟s treatment through tablet splitting. In this case, the patient agreed to change the regime of Apo-Allopurinol® (Allopurinol) 100mg, one and a half tablet daily to become Apo-Allopurinol® 300mg, half tablet daily (Table 1). This recommendation resulted in monthly cost-saving of RM7.80 (US$2.05) to the patient (Apo- Allopurinol® 100mg, 42 tablets cost RM15.60; Apo-Allopurinol® 300mg, 14 tablets cost RM7.80).

In the present study, it was noted that modified release formulation, enteric- coated tablet and narrow therapeutic index drugs were not involved in the splitting recommendations made. Nevertheless, only 32.1% (9 of 28) of the recommendations involved scored tablets with single wide therapeutic drugs which are suitable for splitting (Table 1). The remaining 67.9% (19 of 28) of the cases involved unscored tablets which need further evaluation on its divisibility. All the unscored tablets have symmetrical shape and can be split into two equal halve using appropriate splitting device. Majority (92.9%) of the unscored tablet cases involved single wide therapeutic drug except two cases involved combination tablet which were Co-Diovan® and Fortzaar®. Two drugs in a combination tablet may not evenly distribute throughout the tablet and splitting may not produce equal dose [12]. However, the pharmacist requested consent from the physician when recommending splitting of Co-Diovan® and Fortzaar® and these recommendations was agreed by the physician. Analysis shown the manufacturer of Co-Diovan® (Novartis) disallowed splitting by indicating it is “non-divisible” in the product leaflet. Meanwhile, for all other cases, the product leaflet provides information on the tablet characteristics but does not provide any information about its divisibility. As the product leaflet for Fortzaar® do not include any information regarding its divisibility, the researcher had contacted the manufacturer of Fortzaar® (MSD Malaysia branch) to clarify this issue and found that it can‟t be split. Further analysis on the unscored tablets shows Cozaar® and Zocor® tablet are formulated with a scored line on the lower strength tablet (Cozaar® 50mg and Zocor® 10mg) but are unscored for the higher strength tablet (Cozaar® 100mg and Zocor® 20mg onwards). Besides, studies has shown that tablet splitting for simvastatin and atorvastatin is effective and safe [7][18].

Extent of communication between pharmacists and physicians

Overall, the pharmacists requested consent from the physician for 42.9% of the splitting recommendations. Further analysis shown 33.3% of the antihyperlipidemia agent cases and 41.7% of the cardiovascular drug cases was recommended with reference to the physicians. Besides, 33.3% and 47.4% of cases involved scored and unscored tablet involved consultation with physicians respectively but the differences in these percentages were not statistical significant (Fisher‟s Exact Test, p = 0.687).

Physicians and patients’ acceptance

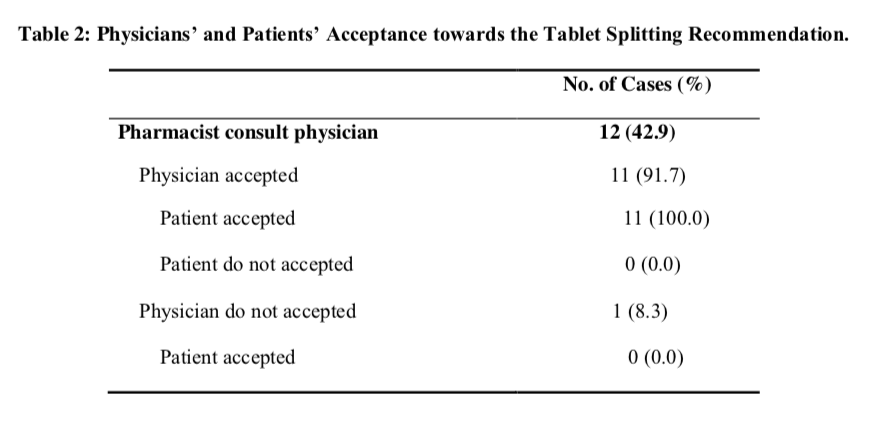

The physicians‟ acceptance rate for tablet splitting recommendations was 91.7% with only one case involved Tenormin® 100mg was rejected. In fact, the entire cases involved unscored tablet was accepted by the physicians.

The overall patients‟ acceptance rate for splitting recommendations was 82.1%. Majority of the patients accepted the recommendations involved anti- hyperlipidemia agents (83.3%) and cardiovascular drugs (75.0%). Meanwhile, the patients‟ acceptance rate for scored and unscored tablet were 66.7% and 89.5% respectively but there was no statistical differences noted with this regard (Fisher‟s Exact Test, p = 0.290). The patients refused to accept splitting recommendation in five cases which involve Tenormin® 100mg, Norvasc® 10mg, Apo-Atenol® 100mg, Zocor® 20mg and Zocor® 40mg respectively. For cases involve consultation with prescriber, 91.7% of the cases was accepted by the patients (Table 2). Further analysis shows that the patients strictly (100.0%) followed the decisions of the physicians. In contrast, 75.0% of cases without informing the physicians were accepted by the patients. Nevertheless, there was no statistical significant difference noted in term of patients‟ acceptance rate between cases involved consultation with the physicians and cases without informing the physicians (Fisher‟s Exact Test, p = 0.355).

Pharmacists’ cost-saving through the tablet splitting recommendation

The cost-saving was calculated for 21 successful tablet splitting recommendation cases. Five cases which refused by the patients and the Co- Diovan® and Fortzaar® case which not allowed to be split were excluded. The total cost for these 21 cases was RM2071.30 (US$545.10) and RM1236.55 (US$325.40) respectively before and after the splitting recommendation. This means the pharmacists expenses on stocks purchasing were reduced by 40.3% or RM834.75 (US$219.70) through the splitting recommendation.

Pharmacists’ monthly cost-saving (per 28 days) for chronic cases

There were 19 successful cases which involved chronic diseases like hyperlipidemia, cardiovascular diseases and diabetic mellitus. The costs of drugs for these cases have been converted to monthly cost (per 28 days). The total monthly cost was RM1586.40 (US$417.45) before the splitting recommendation and reduced by 35.3% to RM 1026.70 (US$270.20) after the recommendation. Total amount of cost- reduction was RM559.70 (US$147.25).

Patients’ cost-saving through tablet splitting

From the 21 cases which accepted by the patients, total cost to the patient before tablet splitting was RM2483.00 (US$653.40). After tablet splitting, the patients‟ total expenses reduced to RM1595.00 (US$419.75). This resulted in cost-saving of RM888.00 (US$233.65), which was 35.8% from the original cost.

Patients’ monthly cost-saving (per 28 days) for chronic cases

From the 19 chronic cases within the two months study, the initial total monthly cost of the patients was RM2034.25 (US$535.35), and declined to RM1292.35 (US$340.10) after the tablet splitting. Consequently, the monthly cost-saving achieved was RM741.90 (US$195.25). The percentage of monthly cost-saving was 36.5% and average monthly cost-saving per patient was RM39.05 (US$10.30).

Discussions

For a period of 2 months, only 28 tablet splitting recommendations were performed by 31.0% of the pharmacists that encounter with opportunities for this practice. This finding revealed that tablet splitting is not a common practice among the community pharmacists. Tablets of patent-protected innovator brands were

more likely to be recommended for splitting than the multi-brands drugs. Therefore, the pharmacists may tend to recommend tablet splitting when cheaper generics are not available. This further supported by the concurrent generic substitution study which observed 158 generic substitution recommendations from the same group of pharmacists [23]. The combination of tablet splitting and generic substitution is a good cost- containment strategy as shown in the case of converting Zocor® 20mg, one tablet daily to Vascor® 40mg, half tablet daily. The cost-saving achieved was four-fold higher than using tablet splitting alone with 76.1% of the cost- saving was contributed by generic substitution.

Overall, majority (92.9%) of the tablet splitting recommendations were appropriate as there were no sustained- release, enteric-coated or narrow therapeutic drugs involved and the tablets involved mostly contain single wide therapeutic drugs. Although majority of the recommendations involved unscored tablets, their symmetrical shapes enable them to be split into fairly equal halve by using proper device. Besides, studies shown that splitting of tablets contain single wide therapeutic drug are clinically appropriate [7][12][18]. Only two cases involved unscored combination tablet (Co-Diovan® and Fortzaar®) were not suitable for splitting. The manufacturers disallowed splitting of these combination tablets because no study being conducted to evaluate patient clinical outcome after the splitting of Co-Diovan® and Fortzaar® tablets. Another interesting finding was only 9.1% (1 of 11) of the manufacturer product leaflets of the unscored split tablets has information on divisibility. This observation was consistent with a finding from primary care centers in Germany where minority (22.5%) of the product leaflet of the

unscored split tablets contained information about the divisibility [11]. Hence, the pharmacists and physicians have limited information on tablet splitting and this may resulted in inappropriate splitting recommendation. The shape of Zocor® and Cozaar® tablets which are unscored in their higher strength are irrational. The manufacturers should scored all strengths of medications which are clinical appropriate for splitting. A study in USA also observed many tablets are scored only in their lower strengths and urged that manufacturer s be compelled to score all strengths of medication [10].

In this study, the pharmacists tend not to consult the physicians when recommending tablet splitting. However, higher percentage of unscored tablet cases involve consultation with physicians as compared to cases which involved scored tablets. These shown the pharmacists may tend to obtain consent from the prescribers for more critical cases. From physicians‟ perspective, majority of the physicians agreed with splitting recommendations by pharmacists. This result was consistent with other study in which consultation between pharmacist and physician improved the cost-effectiveness of prescribing [24]. Meanwhile, majority of the patients agreed to split their tablet and surprisingly, the acceptance rate for unscored tablet was even higher than scored tablet (89.5% versus 66.7%). The high acceptance rate may due to the benefit of cost-saving. Besides, majority of patients (75.0%) accepted the pharmacists‟ recommendations which without a consent from the physician. This showed that the Malaysian pharmacists‟ professional judgment was highly valued by the consumers. Nevertheless, the patients‟ acceptance rate was higher (91.7%) for cases involved consultation with the physicians. This indicated that co-

operations between pharmacists and physicians are very important in improving patients‟ treatment.

The present study also showed that tablet splitting may not only reduce patients‟ expenses on drugs, but it also can reduce pharmacists‟ inventory costs. The patients‟ monthly cost-saving of 36.5% was lower than 61.3% of cost-saving achieved from concurrent generic substitution study [23]. However, this relatively small amount of cost-saving will become a huge amount when accumulated in long term. In addition, this study also highlighted that while performing dispensing, the pharmacists are capable to helping the patients reduce their expenses on drugs while maintaining the efficacy of treatment.

Study limitations

The relatively small sample size limited the generalization of the study findings. The 34 pharmacies involved in this study represented 21.0% of total 165 pharmacies in Penang state and 2.3% of total 1500 pharmacies in whole Malaysia. The duration of two months study was also not sufficient to collect enough tablet splitting cases. Besides, there was no follow-up on the outcome of patients involved in tablet splitting particularly those involved unscored and combination tablets. Based on this study, there is a need to conduct a larger study in Malaysia, using the similar methodology, with longer duration and documented follow-up on the outcome of patients involved in tablet splitting process in order to give a clear picture of tablet splitting practices among Malaysian community pharmacists.

Conclusions

Although tablet splitting is not a popular practice among the community pharmacists, both the physicians and patients were highly accepted the splitting recommendations by the pharmacists and it resulted in significant cost-saving. There is a need to develop a tablet-splitting guideline for health professionals in order to avoid inappropriate splitting recommendation. Furthermore, the manufacturers should score all the tablets of medications which are clinically appropriate for splitting. Sufficient information on divisibility must also be provided on the medication product leaflet.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the pharmacists who voluntarily participated in this study.

Funding

There is no funding provided for this research.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- Lek CS. Health Plan to be modelled after Socso. The Star (Malaysia). 14 December 2005; Available from: http://202.144.202.76/new_mps/cfm/localnews_view.cfm?id=822 (Cited 15 July 2008).

- Hospital drugs to cost more. New Straits Times (Malaysia). 6 December 2004; Available from: http://202.144.202.76/new_mps/cfm/localnews_view.cfm?id=714 (Cited 15 July 2008).

- Babar ZU, Ibrahim M Izaham M. Affordability of medicines in Malaysia- Consumer perceptions. Essential Drugs Monitor 2003; 33:18-19.

- Kennedy J, Coyne J, Sclar D. Drug affordability and prescription noncompliance in the United States: 1997-2002. Clin Ther 2004; 26(4):607-614.

- Miller DP, Furberg CD, Small RH, Millman FM, Ambrosius WT, Harshbarger JS, Ohi CA. Controlling prescription drug expenditures: a report of success. Am J Manag Care 2007; 13: 473-480.

- Yang QH, Liu XB, Cheng SJ. Advantage and disadvantage of split tablets given to patients. J Chin Clin Med 2007; 7(2); Available from: http://www.cjmed.net/html/2007727_118.html (Cited 8 September 2008).

- Gee M, Hasson NK, Hahn T, Ryono R. Effects of a tablet-splitting program in patients taking HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor: analysis of clinical effects, patient satisfaction, compliance, and cost avoidance. J Manag Care Pharm 2002; 8 (6):453-458.

- Dobscha SK, Anderson TA, Hoffman WF, Winterbottom LM, Turner EH, Snodgrass LS, Hauser P. Strategies to decrease costs of prescribing selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors at a VA medical center. Psychiatr Serv 2003; 54(2): 195-200.

- Stafford RS, Radley DC, The potential of pill splitting to achieve cost savings. Am J Manag Care 2002; 8: 706-712.

- Cohen CI, Cohen SI. Potential cost savings from pill splitting of newer psychotropic medications. Psychiatr Serv 2000; 51(4): 527-529.

- Quinzler R, Gasse C, Schneider A, Kaufmann-Kolle P. Szecsenyi J, Haefeli WE. The frequency of inappropriate tablet splitting in primary care. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2006; 62(12):1065-1073.

- Noviasky J, Lo V, Luft DD, Saseen J. Clinical inquiries. Which medications can be split without compromising efficacy and safety? J Fam Pract 2006; 55(8): 707- 708.

- Bachynsky J, Wiens C, Melnychuk K. The practice of splitting tablets. Cost and therapeutic aspects. Pharmacoeconomics 2002; 20(5):339-346.

- Marriott JL, Nation RL. Splitting tablets. Australian Prescriber 2002; 25(6): 133- 135.

- McDevitt JT, Gurst AH, Chen Y. Accuracy of tablet splitting. Pharmacotherapy 1998; 18(1):193-197.

- Rosenberg JM, Nathan JP, Plakogiannis F. Weight variability of pharmacist- dispensed split tablets. J Am Pharm Assoc 2002; 42(2):200-205.

- Teng J, Song CK, Williams RL, Polli JE. Lack of medication dose uniformity in commonly split tablets. J Am Pharm Assoc 2002; 42(2) 195-199.

- Duncan MC, Castle SS, Streetman DS. Effect of tablet splitting on serum cholesterol concentrations. Ann Pharmacother 2002; 36(2): 205-209.

- Fawell NG, Cookson TL, Scranton SS. Relationship between tablet splitting and compliance, drug acquisition cost, and patient acceptance. Am J Health Syst Pharm 1999; 56(24):2542-2545.

- Vuchetich PJ, Garis RI, Jorgensen AMD. Evaluation of cost savings to a state Medicaid program following a Sertraline tablet-splitting program. J Am Pharm Assoc 2003; 43(4): 497-502.

- Weissman EM, Dellenbaugh C. Impact of splitting risperidone tablets on medication adherence and on clinical outcomes for patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv 2007; 58(2): 201-206.

- Generic prescribing and rationalization of tablet strength. Pharmacy audit support pack. RPSGB Scotland. April 2000; Available from: http://www.rpsgb.org.uk/pdfs/generic.pdf (Cited 1 October 2004).

- .Chong CP, Bahari MB, Hassali MA. A pilot study on generic medicine substitution practices among community pharmacists in the State of Penang, Malaysia. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2008; 17:82-89.

- Leach RH, Wakeman A. An evaluation of the effectiveness of community pharmacists working with GPs to increase the cost-effectiveness of prescribing. The Pharm J 1999; 263(7057): 206-209.

Please cite this article as:

Chee Ping Chong, Mohamed Azmi A Hassali and Mohd Baidi Bahari, Evaluation of the Tablet Splitting Practices among Malaysian Community Pharmacists. Malaysian Journal of Pharmacy (MJP). 2012;10(1):12-27. https://mjpharm.org/evaluation-of-the-tablet-splitting-practices-among-malaysian-community-pharmacists/