Abstract

This study was carried out to determine the extent to which demographic characteristic and disease variables are significantly associated with herbal use. This study was a cross sectional survey conducted by structured interview using a validated questionnaire. The subjects were selected using a convenience sampling of 250 patients attending medical wards in Penang Hospital. Univariate and multivariate analysis were performed to examine the predictors of herbal use. The result found 42.4% of participants (n=106) used herbal medicines, with more than one third used herbs and conventional treatments concomitantly (67.9%). A total of 76 patients (30.4%) used herbal medicines in the past 12 months, and 37 (14.8%) patients had ever been used herbs. Multiple stepwise selection logistic regression modelling identified two significant determinants (P<0.05) of herbal use. These were demographic factor, education attainment and disease variable, kidney problem. Study findings indicate that patients with higher education attainment are more likely to use herbal medicines. In contrast, those who suffer from kidney problems are associated with more than three times decreased odds.

Introduction

There is a rapid growing interest in herbal use globally. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 65%-80% of the world’s population use traditional medicine as their primary form of health care.[1] According to WHO, up to 80% of the population in Africa depends on traditional medicine for primary health care and in China, herbal medicines account for 30–50% of total medicinal expenditure. On the other hand, more than 50% of the populations have used complementary or alternative medicine at least once In Europe, North America and other industrialized regions.[2]

Many studies have reported high rate of herbal use in patient population. In a recent survey performed in a primary care setting in Alabama, 26% were taking herbal products and the combined rate of herbal and supplement intake was 48%.3 A cross sectional survey on the use of complementary therapy by ambulatory patients found that almost half of the patients (48.2%) used any vitamins or herbs. As much as 16.4% of patients were using herbal products during the study, 18.3% within the past year, and 22.3% ever.[4] The most commonly used therapies among urban emergency department patients documented in a small study were massage (31%), chiropractory (30%), herbs (24%), and meditation (18%).[5] Studies in other patient populations have also shown a significant prevalence of herbal use.[6][7] Therefore, it is common for patients attending mainstream medical care to use herbs. These studies also supported the complementary role of unorthodox medical therapies in health promotion and disease treatment among patient population.

As herbal medicine is a progressively regular form of complementary therapy used worldwide, the

correlates or predictors of such unconventional therapy among patient population have been of great interest. Numerous studies have examined the association between the demographic predictors and herbal utilization. Although the findings is not unanimous, some of the consistent predictors identified in the literature include being female [8][9], middle age group (25-49 years) [10], higher education level [3][11] , wealthier [12][13], and employed. [14] Perceived poorer health status [12][15], and chronic health problems [5][16] are also potential determinants of herbal use.

Utilization of herbal medicines tends to be higher in some distinct patient population with specific medical conditions such as cancer [6][17], arthritis [18][19], human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease [20], asthma [7][21], and chronic pain [10][12]. Recent survey reported an overall prevalence for herbal preparation use of 13% to 63% among cancer patients.[17] Asthma patients have long been known to use other forms of traditional therapies, including herbal medicines in addition to conventional treatment. A 1997 UK postal survey of 4741 asthmatic patients in an asthma organization revealed that the one year prevalence of alternative therapy was 11% for herbal therapy.[22] Besides, rheumatological problems constituted the greatest percentage of cases being treated by medical practitioners practicing Chinese traditional medicine.[20]

Despite there is well established prevalence estimates of herbal use in most developed countries, similar studies in Malaysia are particularly lacking. Therefore, more information on predictors of herbal utilization based on a representative sample of patient population is required. The study focuses on the herbal use among secondary care patients as this group of patients are usually associated with chronic illness and on long term multiple medications, thereby predisposing the increased risk of adverse effects and drug herb interactions. Information from study may assist in evaluating potential determinants that inspire patients to turn to herbal therapies and facilitate the design of future research on herbal usage. Thus, using patient population that represents ethnic distribution in our society, we aimed to describe the pattern of herbal utilization by multiethnic secondary care patients and determine the extent to which demographic characteristic and disease variables increase the likelihood of herbal utilization. We hypothesized that demographic characteristic as well as presence of chronic medical problems are significantly associated with herbal use.

Method

Sample

A face to face interview using questionnaire was carried out on patients in medical ward, Penang General Hospital. The study population consists of medical patients from cardiology, neurology, infectious and nephrology wards. A convenience sample was selected from all patients attending medical ward, Hospital Pulau Pinang. All eligible patients presented during the study period were included for participation. Patients were excluded if they were below 18 years, pregnant, unable to give consent for any reason, such as having neurological problem or language barrier. A cover letter explaining the purpose of the study was shown to the patients before the consent was obtained. Participation was voluntary. Concurrently, the medical record was reviewed for demographic information, diagnoses, and medications. Overall, data were collected on 250 patients.

Questionnaire

A questionnaire related to study framework was designed. The questionnaire consists of four sections. The first and second part of questionnaire contained questions on demographic and socioeconomic background of respondents. The socio-demographic variables included employment and lifestyle habits (smoking and alcohol consumption) in addition to age, gender, marital status, education and income level. The third section elicits information on perceived health, current medical illness, drug regimen, family history and past medical history. Patients were asked to rate their physical health status, on a standard 5 point Likert scale ranging from excellent to poor. Respondents were also asked whether they had experienced any of a list of 14 health related problems within the past year (Table 2). The final section consisted of questions on the use of herbal medicines, specifying name and details of the herbal medicine used. Patients who use herbal medicine was further classified under current herbal user (past 12 months) and previous users (beyond 1 year or ever been used). Other informations include duration, types of herbs used, registration with Drug Control authority (DCA), Malaysia; and reason for their use (treatment of acute or chronic illness, health maintenance).

Definition of herbal medicines

The terminology used for herbal medicines is non- standard. Most of the previous studies classify herbs under “dietary supplement” which also encompasses vitamins, minerals as in accordance with DSHEA 1994 (Dietary Supplement Heath and education Act). However, this study adopted the definition of herbal medicines as stipulated in World Health Organisation (WHO) guidelines for the appropriate use of herbal medicines in 1998. According to the guidelines, herbal medicine is defined as “plant derived materials or products with therapeutic or other human health benefits which contain either raw or processed ingredients from one or more plants”. Under this definition, there are three kinds of herbal medicines, raw, processed plant materials and medicinal herbal products. Raw plant material is defined as fresh or dry plant materials which are marketed whole or simply cut into small pieces. Processed plant material is defined as plant materials treated according to traditional procedures to improve their safety and efficacy, to facilitate their clinical use, or to make medicinal preparations. Medicinal herbal products is defined as finished, labelled pharmaceutical products in dosage forms that contain one or more of the following: powdered plant materials, extracts, purified extracts, or partially purified active substances isolated from plant materials. Medicines containing plant material combined with chemically defined active substances, including chemically defined, isolated constituents of plants, are not considered to be herbal medicines.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences SPSS version 15.0. Descriptive statistics were used to determine the prevalence of herbal use. Pearson’s Chi-square test, and where necessary Fisher’s exact test were used to determine the association between herbal use and each of the independent variables related to demographic and medical/disease characteristics; a p value of ≤ 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All tests were two tailed. Variables found to be significantly associated with herbal use on univariate analysis were added in a forward stepwise selection to construct the final model of predictor variables.23 Finally, the logistic model, which gives the probability that the outcome (herbal use) occurs as an exponential function of the independent variables (socio-demographic factors) will be derived. Spearman rank correlation coefficient was obtained in order to measure how strongly two independent variables are related to one another.

Result

Descriptive statistics

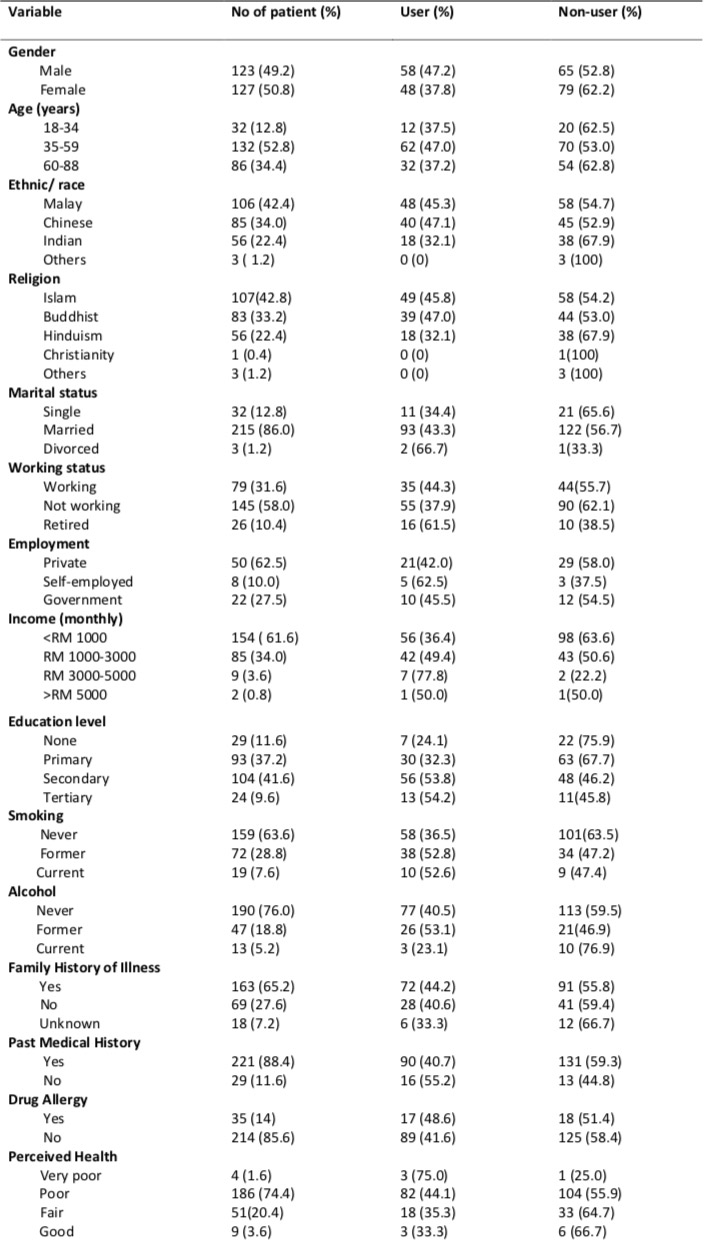

The final study population comprised 127 women (50.8%) and 123 men (49.2%). The mean age was 52.7 years (SD, 15.05; range, 18-86). Malay patients made up 42.4% of respondents, followed by Chinese (34%), Indian (22.4%) and others (1.2%). More than half of the patients’ age fell into age group 35-59 years (52.8%). About 48.8 % of participants had education below secondary level and 61.6% reported to have a gross household income in the lowest category (< RM1000). Most of the patients were unemployed (58%) and for those who are employed, 62.5% joined private sector. Table 1 summarizes socio- demographic characteristics of the subjects included in the analysis.

Socio-demographic characteristic and herbal use

In this study, almost half of the patients (42.4%, n=106) reported using herbs, predominantly men (47.2%). More than one third used herbs and conventional treatments concomitantly (67.9%). The 12 months prevalence of herbal use was 30.4% as compared to 14.8% of patients who had ever used it. The proportions of herbal users varied across ethnic group, with Chinese reported the highest rate of herbal use (47.1%), followed by Malay (45.3%), and Indian (32.1%). Patients in the age group of 35-59 years were found to be major user of herbal medicines (47%). Marital status and employment had no effect on herbal use. A substantially higher percentage of patients with higher income level (> RM 3000) used herbal medicines, as compared to lower income group, with 72.7% and 41% respectively (not shown in data). However, lifestyle habit such as smoking and alcohol consumption had no significant effect on herbal use (Table 1).

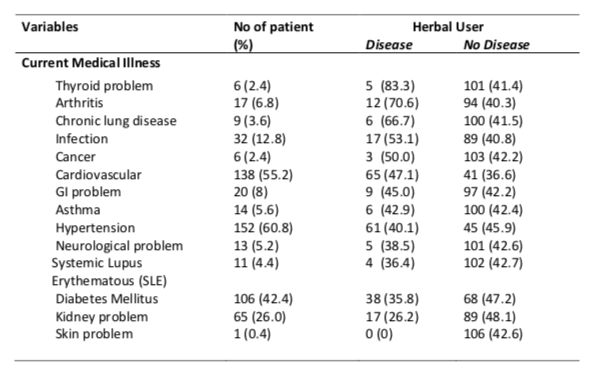

Medical/ disease variables and herbal use

Table 2 shows medical/disease variables associated with herbal use. The 5 most commonly cited medical problems were hypertension (60.8%); cardiovascular problems (55.2%); diabetes mellitus (42.4%); kidney problems (26%); and infection (12.8%). In this study, the percentage of herbal user was found to be higher in patients with the following medical illnesses: thyroid problem (83.3%), arthritis (70.6%), chronic lung disease (66.7%), infection (53.1%), cancer (50%), and cardiovascular problems (47.1%). On the other hand, 65.2% of patients have family history of illness; and 88.4% of patients have past medical history. However, neither family history of illness nor past medical history was associated with higher use of herbal medicine. In total, 74.4% of patients assessed their health as poor. A higher proportion of patients reported very poor and poor perceived health (44.7%) than of patients with fair or good use herbal medicine.

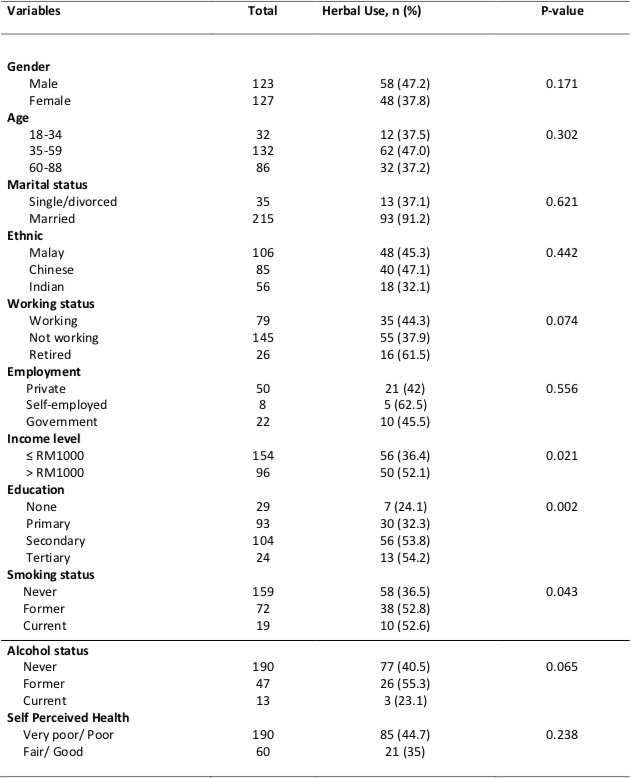

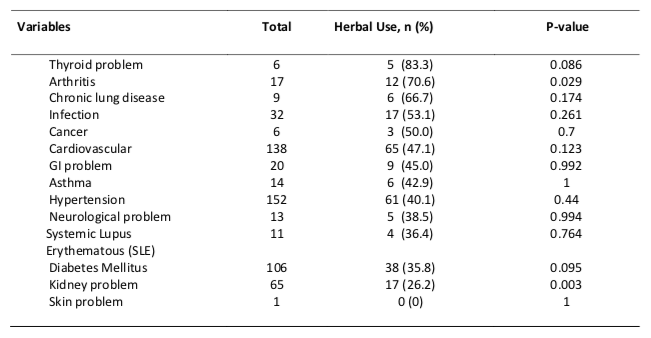

Univariate statistics

Univariate analysis showed that use of herbal medicine correlated positively with sociodemographic characteristic such as education (p=0.002), income level (p=0.021) and smoking status (p=0.043). Medical or disease variables that significantly associated with herbal use were arthritis (p=0.029) and kidney problems (P=0.003). The results of univariate analysis are shown in Table 3 (a) and (b).

To ascertain which of the demographic/ disease variables were independently related to herbal use among medical patients, a logistic regression was conducted. Each of these variables was dummy coded and used as independent variables.

Multiple logistic regression model

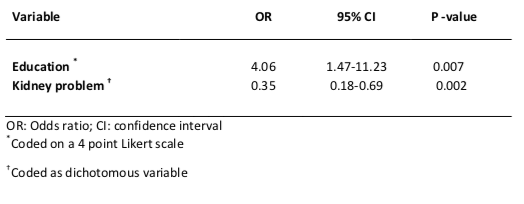

Multiple stepwise selection logistic regression modelling resulted in the final selection of two significant determinants (p<0.05) of herbal use among medical patients. These were: (i) education attainment (OR 4.06; 95% CI 1.47-11.26) and; (ii) kidney problem (OR 0.35; 95% CI 0.18-0.69). Elements strongly associated with herbal use on univariate analysis such as income level, smoking status, and arthritis problem were no longer associated with herbal use when controlled for other variables. Table 4 indicates the adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the independent variables that emerged as significant predictors.

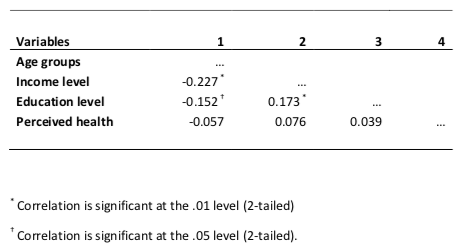

On the other hand, the relationship between age groups, income level, education and perceived health were investigated using Spearman rank correlation coefficient. There was a weak, negative correlation between age groups and income level as well as education level (r= -0.227; p<0.01 and r= -0.152; p<0.05 respectively). Similar observation was found between education and income level except there was a positive correlation between these two variables (r= 0.173; p<0.01). Table 5 presents the intercorrelations of hypothesized predictor variables and use of herbal medicine.

Discussion

Herbal use in survey sample was high and generally consistent with the western population.[3][4] The higher usage of herbal medicine in middle aged patients reported in other studies is in agreement with our results.[11][14] Unlike previous findings [8][9], male patients were the predominant user of herbal medicine in this study. Possible explanation for this discrepancy lies in the adoption of “dietary supplement” definition in prior studies, which also includes vitamins, herbs and functional food. Nevertheless, when the influences of all possible confounders were adjusted, gender was no longer related to an increased use of herbal medicines.

Among ethnic group, Chinese reported with higher rate of herbal use, which is in agreement with prior research.[7] The popularity of traditional medicine among Chinese remains undiminished despite the rapid modernization of mainstream medical care. Herbal use has also been related to various health related behaviour pattern. Former smokers and drinkers used herbal medicine to a greater extent than non-smokers as well as non-drinkers, which is in contrast to previously reported by Gregar.[24] However, when all the possible confounders were taken into consideration, there was no significant effect on the outcome variables.

Most common medical illness correlated with the herbal use in this study was thyroid problem, which is contrary to other reports.[12][19] Nonetheless, study has found that a large percentage of patients with arthritis, chronic lung disease, and cancer used herbal medicines, which corresponds well to other findings.[17][18][25] People who resort to alternative treatment usually have chronic conditions for which modern medicines and synthetic drugs have failed to provide a satisfactory solution. Poor prognosis in cancer (paltiel 2001) and alleged non noxious effects of herbal medicine versus toxic chemotherapy regimen may create demands for natural supplements including herbs. Research indicated that patient with arthritis are more likely to explore alternative medicine in coping with this devastating disease, with an estimated 60-90% of persons with arthritis use complementary therapy.[26]

From the study, we did not observe any statistically significant socio-demographic factors associated with the herbal use except higher education level. This may be attributed to low socioeconomic diversity within the study sample and resulting low variability among the demographic variables. Based on the results from the multiple logistic regressions, education emerged as an important predictor of herbal use.

Unlike other Asian countries [27][28], education that predicted the use of herbal medicine is in basic agreement with that reported in Western countries [8][9] but the new finding in this study is the kidney problem, which requires further investigation.

Education may enhance the chances that people exposed to diverse unconventional therapies, either by advertising media or personal reading of relevant books. However, a controversial saying is that patients with lower education background are more culture-bound [28] and less aware of the importance of evidence based information, thus more likely to conform to alternative therapy.

Our study found an intriguing determinant of herbal disuse, which is kidney problem. Patient with kidney problem was three times less likely to use herbal medicine. The hypothesized explanation is that patient with failing kidney function would not take the risk of more exposure to herbs as the “toxin-filtrating” properties of kidney is well acknowledged.[29] This is further validated by the intrinsic functioning or properties of kidney, where active uptake by tubular cells and high concentration in the medullary region increased the risk of kidney injury.[30] Repetitive stringent warnings by clinicians against using any medications other than those prescribed may also account for decreased likelihood of herbal use.

Various renal syndromes were reported after the use of medicinal plants, including tubular necrosis, acute interstitial nephritis, hypertension, papillary necrosis, and nephrolithiasis.[30] This alarming rate of published data on damaging effect of herbal extracts to kidney may in turn discourage the use of herbal medicines. For example, the mineralcorticoid activity of licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra) is manifested as headache, sodium and water retention, hypokalemia, metabolic alkalosis, hypertension, heart failure, and suppression of the renin-aldosterone system.[30] Many products contain substantial amount of glycyrrhizic acid; namely, health products (herbal cough mixtures, licorice tea, licorice root).[31] This compound can be found in 74% of Chinese herbal teas. [32]

Herbal medicine also may be hazardous for renal patients because of potential drug herb interactions. For example, the immunostimulating effect of Echinacea (Echinacea angustifolia), and licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra), may offset the immunosuppressive effect of cyclosporine, a commonly use drug in kidney transplant .[33] This is particularly important in our study as majority of the kidney patients in our study sample suffered from end stage renal failure and awaiting for kidney transplant. In addition, the effect of cyclosporine will be reduced if co administered with St John’s Wort (Hypericum perforatum), a potential inducer of liver enzymes as these two elements share the common metabolic pathway.[34] The need for nephrologists and other caregivers to elicit information of herbal use among patients is warranted despite the low frequency of herbal use in kidney patients verified in our study.

Conclusion

Our study results indicate that there is no single determinant of the present popularity of herbal medicines exists. Higher education level and kidney problems were significantly correlated with herbal utilization among secondary care patients when the influences of socio-demographic characteristic were adjusted. The growing interest in herbal medicines in local community necessitates continuous evaluation of herbal medicines in all aspects.

References

- Drew AK, Myers SP. (1997) Safety issues in herbal medicine: implications for the health professions. MJA; 166: 538-541

- Bull World Health Organ vol.82 no.3 Geneva (Mar. 2004). WHO issues guidelines for herbal medicines

- Phillips AW, Osborne JA. (2000) Survey of alternative and nonprescription therapy use. Am J Health-Syst Pharm; 57: 1361-1362.

- Rhee SM, Garg VK, Hershey CO. (2004) Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicines by Ambulatory Patients. Arch Intern Med; 164: 1004-1009.

- Rolniak S, Browning L, MacLeod BA et al. (2004) Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among Urban ED Patients: Prevalence and Patterns. J Emerg Nurs; 30: 318-24.

- Paltiel O, Avitzour M, Peretz T et al. (2001) Determinants of the Use of Complementary Therapies by Patients with Cancer. J Clin Oncol; 19: 2439-2448.

- Ng TP, Wong ML, Hong CY et al. (2003) The use of complementary and alternative medicine by asthma patients. Q J Med; 96: 747-754.

- Ni H, Simile C, Hardy AM. (2002) Utilization of Complementary and Alternative Medicine by United States Adults: Results From the 1999 National Health Interview Survey. Med Care; 40: 353-358.

- Kelly JP, Kaufman DW, Kelly K et al. (2005) Recent Trends in Use of Herbal and Other Natural Products. Arch Intern Med; 165: 281-286.

- Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C et al. (1993) Unconventional Medicine in the United States – Prevalence, Costs, and Patterns of Use. N Engl J Med; 328(4): 246-252.

- Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL et al. (1998) Trends in Alternative Medicine Use in the United States, 1990-1997: Results of a Follow-up National Survey. JAMA; 280: 1569-1575.

- Astin JA. (1998) Why Patients Use Alternative Medicine: Results of a National Study. JAMA; 279: 1548-1553.

- Wootton JC. (2001) Surveys of complementary and alternative medicine: Part 1 General trends and demographic groups. J Air Comp Med:7:195-208.

- MacLennan AH, Wilson DH, Taylor AW. (1996) Prevalence and cost of alternative medicine in Australia. Lancet; 347: 569-573.

- Paramore LC. (1997) Use of alternative therapies: estimates from the 1994 Robert Wood Johnson Foundation national Access to care survey. J Pain Symtoms Management; 13: 83-9.

- Bausell RB, Lee WL, Berman BM. (2001) Demographic and Health-Related Correlates of Visits to Complementary and Alternative Medical Providers. Med Care; 39: 190-196.

- Sparreboom A, Cox MC, Acharya MR, Figg WD. (2004) Herbal Remedies in the United States: Potential Adverse Interactions With Anticancer Agents. J Clin Oncol; 22: 2489-2503.

- Soeken KL, Miller SA, Ernst E. (2003) Herbal medicines for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Rheumatology; 42: 652-659.

- Ernst E. (2000) The role of complementary and alternative medicine. BMJ; 321: 1133–5

- O’Brien K. (2004) Complementary and alternative medicine: the move into mainstream health care. Clin Exp Optom; 87(2): 110-120.

- Partridge MR, Dockell M, Smith NM. (2003) The use of complementary medicines by those with asthma. Respir Med; 97: 436-8.

- Ernst E. (1998) Complementary therapies for asthma: what patients use. J Asthma, 35:667–671.

- Katz MH. (1992) Multivariable Analysis – A Practical Guide for Clinicians. 1999 Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (example: Meehan TC. Therapeutic touch, 2nd edn. Philadelphia, PA: W B Saunders,:pp201-212)

- Gregar JL. (2001) Dietary supplement use: consumer characteristic and interest. J Nutr; 131(S): 1339S-1343S.

- George J, Ioannides-Demos L, Santamaria N et al. (2004) Use of complementary and alternative medicines by patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. MJA; 181: 248-251.

- Rao J et al. (1999) Use of complementary therapies for arthritis among patients of rheumatologists. Ann Intern Med; 131: 409–163.

- Huba GJ, Melchior LA. The Measurement Group and HRSA/HAB’s SPNS Cooperative Agreement SteeringCommittee Module 26B: CES-D8 Form (Availableat www.TheMeasurementGroup.com. Culver City, California).

- Lee GBW, Charn TC, Chew ZH, Ng TP. (2004) Complementary and alternative medicine use in patients with chronic diseases in primary care is associated with perceived quality of care and cultural beliefs. Family Practice; 21: 654-660

- Rang HP, Dale MM, Ritter JM. (1996) Pharmacology, General principles: absorption, distribution and fate of drugs, 3rd edn. Churchill,:pp 87-90

- Bagnis CI, Deray G, Baumelou A et al. (Dis 2004) Herbs and the Kidney. Am J Kidney; 44: 1-11.

- De Klerk GJ, Nieuwenhuis MG, Beutler J (1997) Lesson of the week: Hypokalaemia and hypertension associated with the use of liquorice flavored chewing gum. BMJ 314:731-735

- Winslow LC, Kroll DJ (1998) Herbs as medicines. Arch Intern Med 158:2192-2199

- Miller LG. Herbal Medicinals (1998) Selected Clinical Considerations Focusing on Known or Potential Drug-Herb Interactions. Arch Intern Med; 158: 2200-2211.

- Wojcikowski K, Johnson DW, Gobe G. (2004) Medicinal herbal extracts – renal friend or foe? Part one: The toxicities of medicinal herbs. Nephrology; 9: 313-318.

- Al-Windi A. (2004) Determinants of complementary alternative medicine (CAM) use. Complementary Therapies in Medicine; 12: 99-111.

- Aziz Z. (2004) Herbal medicines: predictors of recommendation by physicians. J Clin Pharmacy Therapeutics; 29: 241-246.

- Barnes J, Mills SY, Abbot NC et al. (1998) Different standards for reporting ADRs to herbal remedies and conventional OTC medicines: face-to-face interviews with 515 users of medical remedies. Br J Clin Pharmacol; 45: 496-500.

- Begbie SD, Kerestes ZL, Bell DR. (1996) Patterns of alternative medicine use by cancer patients. Med J Aust;165:545-548

- Cassileth BR, Deng G. (2004) Complementary and Alternative Therapies for Cancer. Oncologist; 9: 80-89.

- De Jong N, Ocke MC, Branderhorst H et al. (2003) Demographic and lifestyle characteristics of functional food consumers and dietary supplement users. Br J Nutrition; 89: 273-281.\

- Eisenberg DM. (1997) Advising Patients Who Seek Alternative Medical Therapies. Ann Intern Med; 127(1): 61-69.

- Györik SA and Brutsche MH. (2003) Complementary and alternative medicine for bronchial asthma: is there new evidence? Curr Opin Pulm Med; 10: 37–43

- Kessler RC, Davis RB, Foster DF et al. (2001) Long-Term Trends in the Use of Complementary and Alternative Medical Therapies in the United States. Ann Intern Med; 135: 262-268.

- Kuo GM, Hawley ST, Weiss LT et al. (2004) Factors associated with herbal use among urban multiethnic primary care patients: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Complementary Alternative Medicine; 4:18.

- WHO. Traditional Medicine – Growing Needs and Potential. WHO Policy Perspective on Medicine No.2 May 2002. WHO, Geneva.

- Wojcikowski K, Johnson DW, Gobe G. (2004) Medicinal herbal extracts – renal friend or foe? Part two: Herbal extracts with potential renal benefits. Nephrology; 9: 400-405.

- Zollman C, Vickers A. (1999) ABC of complementary medicine: What is complementary medicine? BMJ; 319: 693-696.

Please cite this article as:

Mohd Baidi Bahari and Saw June Tze, Predictors of Herbal Utilization by Multiethnic Secondary Care Patients in Malaysia: a Cross Sectional Survey. Malaysian Journal of Pharmacy (MJP). 2011;9(1):325-335. https://mjpharm.org/predictors-of-herbal-utilization-by-multiethnic-secondary-care-patients-in-malaysia-a-cross-sectional-survey/