Objectives: To determine the relationship between medication adherence and psychotic symptoms before and after introducing a pill box. Methods: A pre- and post- interventional, prospective cohort study involving 96 patients diagnosed with schizophrenia was conducted over a duration of 2 months. Improvement in psychotic symptoms was assessed using the BPRS scale, while medication adherence was measured based on the percentage of doses taken. A pill box was provided to each subject with a percentage of doses that was taken less than 80%. The percentage of doses taken was reassessed by a trained pharmacist on a monthly basis for 2 months, and the mental state of participants was assessed by a visiting doctor using the BPRS scale. Results: The mean medication adherence during the first visit was 31.27 ± 28.77, while post-intervention adherence averaged 66.48 ± 43.52 (p-value <0.001). In terms of severity of psychotic symptoms, 26 subjects (43.3%) with a median score of 20.50 showed improvement. A total of 36 subjects adhered to antipsychotic medications, and among these, 20 (55.6%) showed improvement in psychotic symptoms (p=0.019). Among the 24 non-adherent subjects, only 25% (n=6) showed improvement in psychotic symptoms. Conclusion: The introduction of a pill box positively affects medication adherence and reduces the severity of psychotic symptoms. This study suggests that healthcare personnel can implement this method to promote better adherence to medication in the future.

INTRODUCTION

Schizophrenia is a serious mental disorder with a relatively high prevalence, affecting about 7 per 1000 adults worldwide. It is a persistent, long-term condition.[1]. People with chronic illness, regardless of whether they are medical or psychiatric, need to be on regular medications for life in order to manage symptoms effectively and reduce the risk of relapse. The use of antipsychotics is crucial in treating schizophrenia as well as the symptoms of the illness.

Therefore, medication adherence is essential for patients to achieve remission. However, non-adherence to these medications has been recognized as a significant problem [2]. The majority of clinicians encounter adherence issues with patients regarding prescribed medications, and this issue is more pronounced in patients with psychiatric illness. The adherence rate among patients who are diagnosed with schizophrenia falls between 50% and 60% [3][4]. One study stated that poor psychiatric reasoning skills and lack of insight are the reasons for poor adherence among psychiatric patients [4].

Medication adherence refers to a patient’s behaviour in taking medications and specifically denotes the extent to which a patient follows the mutually agreed-upon treatment plan established by their healthcare providers [5]. Research has shown that non-adherence to antipsychotics among schizophrenia patients leads to a higher risk of relapse and readmission, increased risk of violence towards society, suicidal risk and attempts, as well as elevated costs and resource use for healthcare systems [1][5]. Patients with schizophrenia are considered adherent to therapy if they achieve a compliance rate of 80% with their prescribed medications, while partial adherence is defined as compliance of 50%. Non-adherence is defined as being off medications for 1 week or longer [6][7]. A recent study conducted in Sweden showed that 861 patients experienced early rehospitalisation shortly after discharge due to non-adherence to their prescribed antipsychotic medications [8]. This, in turn, leads to an increased disease burden on healthcare systems [9]. Efforts to improve medication adherence among individuals with schizophrenia are crucial, as they contribute to better symptom management, reduced psychiatric complications, lower healthcare expenses, and an overall improvement in the patient’s welfare and quality of life [10].

Various interventions have been implemented to improve adherence to medication regimens among patients with psychiatric illnesses. At Hospital Kuala Lumpur (HKL), psychiatry patients with severe mental illness are referred to Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) if they are found to be non-adherent to treatment, have limited social support, and have experienced multiple relapses. In ACT, a team consisting of a psychiatrist, a medical officer, a pharmacist, case managers (medical assistants or staff nurses), occupational therapists and social work officers helps patients manage their illness by ensuring adherence, mobilizing support, monitoring symptoms, and providing continuous psycho-education regarding their illness, symptoms and treatment to improve patients’ quality of life. The pill box is one of the interventions used in ACT to increase patients’ adherence to their medications. Pill counting is more reliable than self-reporting or informant reporting, which may be influenced by opinion, recall bias, and a tendency to obscure the truth. In contrast, a pill box is more organized and may help patients improve their adherence to medications.

However, there are no specific studies on this intervention conducted for patients with mental illness, especially schizophrenia, in Malaysia. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the effect of medication adherence with the use of a pill box on the improvement of psychotic symptoms among patients with schizophrenia under assertive community care in Hospital Kuala Lumpur (HKL).

MATERIAL AND METHOD

Study design and patient selection

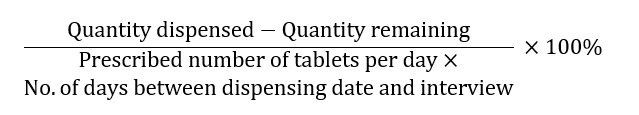

A pre- and post- interventional, prospective cohort study was conducted with approved registration ID by National Medical Research Register: NMMR-19-4019-51115. Study samples were collected among psychiatric patients referred for ACT in the Psychiatry Department of HKL using convenience sampling. Patients enrolled had to fulfil the following inclusion and exclusion criteria. All subjects were assessed for their mental status using Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS and BPRS-M), and non-adherence to medications was defined as patients taking less than 80% of prescribed doses. Subjects who were chosen into this study could be of those who had not or had used a pill box prior to the study. Those subjects who were within the range of 18 to 65 years old, with clinically diagnosed schizophrenia only, on a single oral antipsychotic that was maintained for the past three months, and who had provided consent. Exclusion criteria included subjects who were actively abusing substances during the study period, who had never tried using a pill box prior to the study, had other medical diagnoses (based on self-report and clinician report), and patients with a BPRS total score above 53, indicating they were markedly ill and not fit to give consent. The formula used for calculating the percentage of dose taken (% adherence) was as follows:

Percentages of dose taken =

All subjects were introduced to a pill box by a pharmacist to monitor medication adherence throughout the study period. The pill box was filled with subjects’ dose regimen on a monthly basis. The pharmacist in charge will provide information to the subject and his/her caretaker on how to use the pill box in a correct manner. Assertive community care was then continuously maintained for these subjects. During this study, all subjects were assessed using the pill count adherence method for existing medications and the BPRS.

Medication refills for subjects and pill counts were done by a pharmacist, while mental status was assessed by the visiting doctor. The percentage of doses taken and mental status were reassessed during the second and third month of the ACT, respectively. The study data collection period lasted 12 months.

Assessment

Psychiatric symptoms were evaluated using either the BPRS or BPRS-M based on the preferences of the visiting doctor and patient [11]. Each item of the BPRS was assessed during each ACT session to determine the severity of psychotic symptoms among subjects. The BPRS scale had a minimum score of 18 and a maximum of 126. Scores within the range of 31 to 40 corresponded to mild psychotic symptoms; 41-52 indicated moderate psychotic symptoms, while a score above 53 indicated markedly ill subjects. Each item in the BPRS was rated from 0-7 based on symptom severity, where the highest score indicated the highest severity.

Data analysis

The collected data were analysed using descriptive statistics, paired t-test, Wilcoxon signed-rank test, and Pearson’s chi-square test. Descriptive analysis was used for the demographic analysis. Paired t-test was used to assess the difference in medication adherence before and after the introduction of the pill box whereas Wilcoxon Signed rank test was used to determine the median of the BPRS score among these subjects. The association between medication adherence and improvement in psychotic symptoms was assessed using Pearson chi square test. All statistical analyses were analysed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS version 20.0) for Windows. Statistical significance was set at a p-value of < 0.001.

RESULT

The total number of patients with mental illness referred to the Community Psychiatry Unit of the Psychiatry Department of Hospital Kuala Lumpur (HKL) was approximately 539 patients, including 350 patients diagnosed with schizophrenia along with other psychiatric diagnoses or medical comorbidities, while 100 patients had a diagnosis of schizophrenia only. Out of the 100 eligible patients, only sixty subjects agreed to be recruited into the study over 2 years, from July 2019 to May 2021. The demographic data of these subjects are presented in Table Ⅰ. The majority of the subjects fell within the age group of 40 to 49 years old (38.3%), with male subjects comprising 61.7% of the sample size. Among the 60 subjects, 46 (76.7%) were of Malay descent. The employment status of the subjects was predominantly unemployed (85%).

All subjects recruited for the study had a medication adherence score of less than 80% and were given a pill box. The mean medication adherence during the first visit was 31.27 ± 28.77, while the post-intervention mean was 66.48 ± 43.52 (p <0.001). The psychotic symptoms experienced by the subjects were assessed using the BPRS on the first day of the study. The subjects were then reassessed during the second and third visits. Out of the 60 subjects, 26 (43.3%) showed improvement in psychotic symptoms, with a median score of 20.50 (19-21.5). These subjects showed a 20% improvement in the BPRS scores throughout the study. Tables Ⅱ and Ⅲ show the impact of the pill box introduction on medication adherence and the improvement of psychotic symptoms among these 60 subjects, respectively.

The relationship between medication adherence and psychotic symptoms was assessed. A total of 36 subjects adhered to their anti-psychotic medications, and out of these, 20 showed improvement in psychotic symptoms, comprising 55.6% (n=20) of the subjects (p=0.019). Among the 24 non-adherent subjects, only 25% (n=6) showed improvement in psychotic symptoms

(Figure Ⅰ). A Pearson chi-square statistical test was used to examine the relationship between these two variables after the introduction of the pill box.

| Characteristics | Frequency (n, %) |

| Age (years old) | |

| 20-29 | 5 (8.3) |

| 30-39 | 13 (21.7) |

| 40-49 | 23 (38.3) |

| 50-59 | 13 (21.7) |

| More than 60 | 6 (10.0) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 37 (61.7) |

| Female | 23 (38.3) |

| Race | |

| Malay | 46 (76.7) |

| Chinese | 8 (13.3) |

| Indian | 6 (10.0) |

| Employment status | |

| Unemployed | 51 (85.0) |

| Employed | 9 (15.0) |

| Variable | Mean ± SD (Pre) | Mean ± SD (Post) | p-value |

| Improvement in medication adherence | 31.27 ± 28.77 | 66.48 ± 43.52 | < 0.001 |

| Variable | Median (Pre) | Median (Post) | p-value |

| Improvement in psychotic symptoms (BPRS score) | 25.00 (28-23) | 20.50 (22-18.5) | < 0.001 |

DISCUSSION

In this prospective cohort study, patients on a single oral antipsychotic that had not been changed for the past three months were selected. Although a modest number of patients were recruited in this study, the introduction of the pill box appeared to lead to improvements in medication adherence and control of psychotic symptoms among schizophrenia patients. More than half the patients showed improvement in medication adherence when the pill box was provided as an aid to increase compliance with their medications. Our findings suggest the benefits of such aids in enhancing medication adherence; however, this still depends on factors such as the severity of psychiatric symptoms and therapeutic response (which were controlled and monitored in this study). Other factors, such as the patient’s attitude towards treatment, perceptions or insights regarding the need to take medications, duration of illness, and side effects, were not studied but may also affect medication adherence [6][12]. Patients with better insight into their illness and medications tend to show improvement in medication adherence, which, in turn, supports the achievement of recovery goals and optimizes overall patient wellness [6][13]. Adherence to antipsychotics has shown significant improvement in patients with schizophrenia and can reduce the percentage of relapse in the future [1][2][5][14]. The use of the pill box was also shown to help patients prevent overdosing or underdosing during the treatment course, given the nature of the illness. Studies by Diaa S et al. stated that the pill box can also remind patients about the timing of their prescribed medications [15][16]. This is essential for schizophrenic patients, as the timing of antipsychotic administration is crucial for cognitive function. The pill box also helps prevent medication errors, such as taking the wrong medications, and patients can be educated to organize their medications in the pill box throughout the treatment course [17][18].

About half of the patients showed improvement in psychotic symptoms with the use of the pill box. Patients’ compliance has been associated with improvement in psychotic symptoms through adherence to the treatment plan. However, the other half of the patients showed no improvement in psychotic symptoms despite being adherent to treatment. The fact that adherent patients did not achieve significant improvement in psychotic symptoms could be due to non-response to the medications, ongoing and recent stressors, poor family support, high emotional expressiveness within their families, or unsuitable medications. Further treatment interventions should be tailored to patients, such as optimizing oral antipsychotic dosages and durations, considering combination therapy with other oral antipsychotics or mood stabilisers, switching to long-acting injectables, or employing electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Additionally, optimizing psychosocial interventions involving family members’ psychoeducation is vital [19][20][21]. Evidence from some studies also shows that this will eventually lower psychiatric morbidity, reduce the cost of care, and improve overall welfare and quality of life of patients and family members [8][22]. This study was conducted among patients receiving assertive community care; however, these results can be applicable in both outpatient and inpatient settings, as the introduction of the pill box can be implemented in any setting, provided that proper education on its use is given by pharmacists and proper monitoring occurs during clinical follow ups.

Limitations

The study had several limitations. The overall planned sample size was 96 patients diagnosed with schizophrenia. However, only 60 patients agreed to participate in this study, while others faced limitations due to the Covid-19 pandemic, time constraints from the Movement Control Order (MCO) implemented during the study period, and a lack of family support due to stigmatization.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that the introduction of a pill box for patients with schizophrenia has a positive impact on psychotic symptoms, which have improved as a result. Medication adherence also increased when the pill box was introduced to this group of patients. Given the connection between medication adherence and the improvement of psychotic symptoms in schizophrenic patients, this approach may improve quality of life and reduce psychiatric morbidity. In the future, psychiatric departments should implement the use of pill boxes during the continuation of treatment outside the hospital.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to our head of Community Psychiatric Service (CPS), HKL, Datin Dr. Riana Binti Abdul Rahim for granting permission for this research to proceed. The authors gratefully acknowledge the dedication and assistance given by our case managers and staff of CPS HKL, all medical officers and pharmacists involved during the study period. Besides that, utmost grateful is conveyed to Badan Kebajikan Psikiatri (BKP), Hospital Kuala Lumpur.

REFERENCE

- World Health Organization. Schizophrenia. Geneva: World Health Organization 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/factsheets/detail/schizophrenia

- Higashi K, Medic G, Littlewood KJ, Diez T, Granström O, De Hert M. Medication adherence in schizophrenia: factors influencing adherence and consequences of nonadherence, a systematic literature review. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol 2013; 3(4): 200–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/2045125312474019

- Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med 2005; 353(5): 487-97. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmra050100

- Semahegn A, Torpey K, Manu A, Assefa N, Tesfaye G, Ankomah A. Psychotropic medication non-adherence and associated factors among adult patients with major psychiatric disorders: a protocol for a systematic review. Syst Rev 2018: 7(1): 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0676-y

- Alene M, Wiese MD, Angamo MT, Bajorek BV, Yesuf EA, Wabe NT. Adherence to medication for the treatment of psychosis: rates and risk factors in an Ethiopian population. BMC Clin Pharmacol 2012; 12: 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6904-12-10

- Peggy E, Jan F. Strategies to improve medication adherence in patients with schizophrenia: the role of support services. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2015; 11: 1077– 1090. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S56107

- Kane JM, Kishimoto T, Correll CU. Non adherence to medication in patients with psychotic disorder: epidemiology,contributing factors, management strategies. World Psychiatry 2013; 12(3): 216–226. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20060

- Bodén R, Brandt L, Kieler H, Andersen M, Reutfors J. Early non-adherence to medication and other risk factors for rehospitalization in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Schizophr Res 2011; 133(1-3): 36–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2011.08.024

- Knapp M, King D, Pugner K, Lapuerta P. Non-adherence to antipsychotic medication regimens: associations with resource use and costs. Br J Psychiatry 2004; 184: 509–516. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.184.6.509

- Byerly MJ, Nakonezny PA, Lescouflair E. Antipsychotic medication adherence in schizophrenia. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2007; 30(3): 437–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2007.04.002

- Yee A, Ng BS, Hashim HMH, Danaee M, Loh HH. Cultural adaptation and validity of the Malay version of the brief psychiatric rating scale (BPRS-M) among patients with schizophrenia in a psychiatric clinic. BMC Psychiatry 2017; 17(1), 384. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1553-2

- Azrin NH, Teichner G. Evaluation of an instructional program for improving medication compliance for chronically mentally ill outpatients. Behav Res Ther 1998; 36(9): 849–861. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00036-9

- Maneesakorn S, Robson D, Gournay K, Gray R. An RCT of adherence therapy for people with schizophrenia in Chiang Mai, Thailand. J Clin Nurs 2007; 16(7): 1302-1312. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.01786.x

- Haddad PM, Brain C, Scott J. Nonadherence with antipsychotic medication in schizophrenia: challenges and management strategies. Patient Relat Outcome Meas 2014; 5: 43–62. https://doi.org/10.2147/prom.s42735

- Abdul Minaam DS, Abd-ELfattah M. Smart drugs: Improving healthcare using Smart Pill Box for Medicine Reminder and Monitoring System. Future Computing and Informatics Journal 2018; 3(2): 443-456. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.fcij.2018.11.008

- Choudhry NK, Krumme AA, Ercole PM, Girdish C, Tong AY, Khan NF, et al. Effect of Reminder Devices on Medication Adherence: The REMIND Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med 2017; 177(5): 624-631. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9627

- Conn VS, Ruppar TM, Chan KC, Dunbar-Jacob J, Pepper GA, De Geest S. Packaging interventions to increase medication adherence: systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Med Res Opin 2015; 31(1): 145–160. https://doi.org/10.1185/03007995.2014.978939

- Choi EPH. A Pilot Study to Evaluate the Acceptability of Using a Smart Pillbox to Enhance Medication Adherence Among Primary Care Patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019; 16(20): 3964. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16203964

- Clinical Practice Guidelines on Management of Schizophrenia in adults. Ministry of Health Malaysia 2009. https://www.moh.gov.my/moh/attachments/2641.pdf

- Loots E, Goossens E, Vanwesemael T, Morrens M, Van Rompaey B, Dilles T. Interventions to Improve Medication Adherence in Patients with Schizophrenia or Bipolar Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18(19): 10213. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910213

- Barkhof E, Meijer CJ, de Sonneville LM, Linszen DH, de Haan L. Interventions to improve adherence to antipsychotic medication in patients with schizophrenia-a review of the past decade. Eur Psychiatry 2012; 27(1): 9-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2011.02.005

- Serobatse MB, Du Plessis E, Koen MP. Interventions to promote psychiatric patients’ compliance to mental health treatment: A systematic review. Health SA Gesondheid 2014; 19(1): 1-10. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hsag.v19i1.799

Please cite this article as:

Selene Joseph, Hasniah Husin, Muhammad Umar Azree, Nevethiga, Kar Yin Lee and Norhayati, The Effect of Medication Adherence on the Improvement of Psychotic Symptoms among Patients with Schizophrenia under Assertive Community Care in Hospital Kuala Lumpur. Malaysian Journal of Pharmacy (MJP). 2025;1(11):16-20. https://mjpharm.org/the-effect-of-medication-adherence-on-the-improvement-of-psychotic-symptoms-among-patients-with-schizophrenia-under-assertive-community-care-in-hospital-kuala-lumpur/