Abstract

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality globally. Identification of common risk factors and risk stratification helps to prioritize primary preventive measures and hence can reduce this epidemic. This retrospective cross sectional study was carried out to assess the primary preventive measures according to 10 years CHD risk stratification. One hundred thirty (67 female and 63 female) middle aged (40-65 years) patients admitted to PPUKM’s medical ward with no prior diagnosis of CHD were selected. Patient diagnosed with diabetes or hypertension related to pregnancy was excluded. The patients’ medical record and order management system (OMS) were screened to obtain relevant demographic information, medical and medication history and related laboratory results. The Joint British Societies CHD risk prediction chart was used to calculate the 10 years CHD risk. Gender specific differences of 10 years calculated CHD risk, baseline measure of BP, cholesterol, weight, BMI, HbA1C level and number of patients who received primary preventive measures were used as outcome measures. Results showed that male patients had a significantly higher 10 years CHD risk than female (P < 0.05). Hypertension was the most prevalent risk factor followed by diabetes and dyslipidemia. About10% (n=6) of hypertensive patients with SBP≥160 mmHg and 32 (37%) diabetic patients did not receive antihypertensive therapy and lipid lowering therapy respectively. Hence, there is a need for further improvement in primary preventive measures for CHD.

Introduction

CHD is the principal cause of morbidity and mortality in many countries world-wide. WHO (2001) estimated that by the year 2020, it will be the single largest cause of disease burden globally. According to department of statistics of Malaysia, CHD is among the three leading cause of medically certified death in Malaysia. National heart association of Malaysia (2009) estimated that CHD afflicted 141 persons/100,000 populations each year.

Risk factors for CHD which are defined and confirmed by the Framingham study conducted by Gordon et al. (1977) and other interventional trials include, male gender, advanced age, family history of early heart disease, cigarette smoking, high blood pressure, high blood cholesterol, being overweight, physical inactivity, and diabetes. However, these studies were conducted predominantly on Caucasian and migrant Asian populations. Recently there is a growing interest to examine the impact and role of established risk factors of CHD on Asian population in times of economic advancement and modernization in Asia (Jeannette et al 2001).

Global risk assessment is an approach to CHD prevention that estimates the absolute risk based on the summation of risks contributed by each risk factor. The risk factors do not add their effects in a simple way. Rather, they multiply each other’s effects. Although not all risk factors are modifiable, all can contribute to the risk assessment, and the intensity of risk factor management can be adjusted according to the severity of the overall risk.

Primary prevention of CHD requires modification of risk factors or prevention of their development with the aim of delaying or preventing new-onset CHD. The National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel guidelines (NCEP ATP III) provide recommendations for CHD prevention, focusing on lipid lowering by adjusting the intensity of cholesterol lowering therapy with absolute risk. As indicated in the report by joint national committee (1993), the National High Blood Pressure Education Program (NHBPEP) has set forth a parallel approach for blood pressure control. In contrast to the NCEP, however, earlier NHBPEP reports did not match the intensity of therapy to absolute risk for CHD. “Normalization” of blood pressure is the essential goal of therapy regardless of risk status.

This study was set to determine the occurrence of common risk factors and global assessment of these risk factors to examine the extent of primary preventive measures based on the risk stratification and furthermore, it looked into the trends of prescribing for antihypertensive and lipid lowering agents for primary prevention of CHD.

Methods

This is a retrospective, cross-sectional survey that included conveniently sampled participants admitted to medical ward of PPUKM between the year 2007 and 2008. Patients’ information about their age, sex, race, medical condition, medication history and related laboratory results were obtained from patients’ medical record and the order management system (OMS).

The study utilized the Joint British Societies (JBS) CHD risk prediction charts to calculate the 10 years CHD risk. The British risk prediction chart is superior to other risk assessment methods because it directly plots the Framingham function for a given level of absolute CHD risk resulting in more accurate value. Furthermore, this method represents the Framingham data more appropriately than other charts since it stratifies the CHD risk into three categories (<15% (green band), 15-30% (orange band) and >30% (red band)).

The study included patients between 40 and 65 years of age without a prior diagnosis of CHD. The patients < 40 years of age are not recruited for the study since JBS cannot be used to accurately predict the CHD risk in this age group. Patients with diabetes or hypertension related to pregnancy are excluded. Missing values were considered as absent (zero). Subjects were considered smokers if they were reported as smokers regardless of the number of cigarettes they smoke daily and they are

considered as previous smokers if they stopped smoking for at least 6 months (Larabie 2005).

Hypercholesterolemia is defined according to the categories indicated on the NCEP ATPIII guidelines. Patients having ≥ 30 kg/m2 body mass index (BMI) were considered obese. Respondents were considered to have diabetes if they were reported to be diagnosed with diabetes in past year, or have a blood sugar level greater than or equal to 126 mg/dL or if were prescribed with oral hypoglycaemic agent or insulin. Hypertension was considered present if respondents had a reported high blood pressure (SBP ≥ 140 mm Hg and DBP ≥90 mm Hg) on two or more occasions or if they were ever prescribed medication to lower their blood pressure. Family history was considered present if the record indicated diagnosis of CHD or stroke (TIA) in first degree relatives regardless of age of onset.

Outcome Measures

The outcome measures include baseline measure of BP, cholesterol, weight, BMI, HbA1C level, 10 years calculated risk of CHD, and proportion of patients who received primary preventive measures, trends of prescribing for primary prevention.

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were performed using SPSS version 15.0 for window. Descriptive statistics was used to characterize respondents, chi-square tests to assess differences in proportions, and the student t test to assess differences in means. The difference is considered significant for a statistical P value of P < 0.05.

Results

A total of 200 patients medical records were screened for this study and 130 (67 female and 63 male) patients were included based on the inclusion criteria. Malays accounted for 53% (n=69) of the population studied (n=130) while the remaining 47% were Chinese (n=47, 36%), Indians (n=13, 10%) and other races (n=1, 1%).

The (mean ± SD) age and weight of the study population was 55.54 ± 6.764 years and 66.0 ± 13.08kg. The BMI was calculated for 105 patients, 17% (n=18) were found to obese (BMI ≥ 30kg/m2) and 27% (n=28) were overweight (BMI between 25-30 kg / m²).

A total of 23.8% (n=31) of the subjects were current smokers and 27 (20.7%) subjects had stopped smoking in the previous 6 months to 3 years.

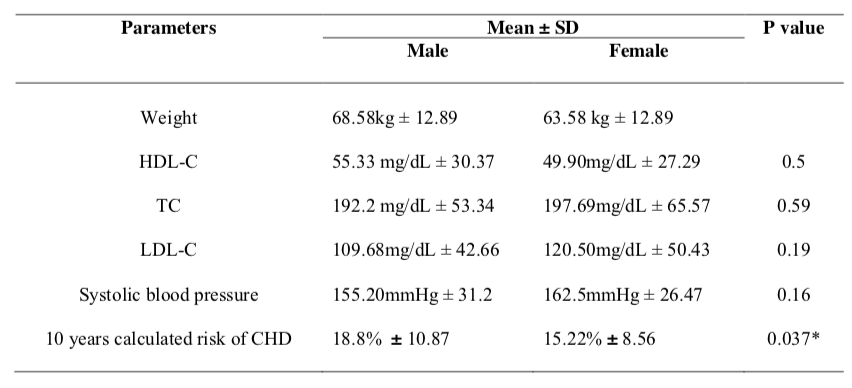

The difference for measured baseline TC, HDL-C, LDL-C and SBP between male and female was not significant (P > 0.05). Similarly there was no significant difference between different races with regard to calculated 10 years CHD risk. The calculated 10 years CHD risk differed significantly between male and female subjects at level of t(128) =2.106, P < 0.05 (Table 1).

Family history record was not found for 23 % of the study population. For those with family history records, 63.85% did not have any history of CHD, while 13.08% were indicated to have family history of CHD.

Hypertension is the most common risk factor in this study population and 25.6% (32) of the patients were treated with monotherapy while dual therapy and multiple drug therapy (≥3drugs) was given to 35% (42) and 24% (29) of the patients correspondingly. Conversely, 15% (n=13) of patients did not receive any drug for the management of their high blood pressure.

Discussion

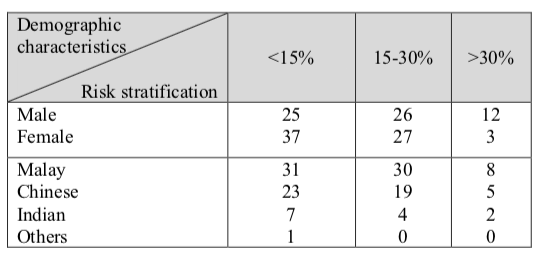

The findings of the study showed that 52 % (n=68) of the population have a 10 years CHD risk greater than or equal to 15% according to the JBS CHD prediction chart risk category.

The 10-year risk stratification for CHD provide guidance for prioritizing primary prevention measures of CHD. The remaining 48 % (n=62) were found to have low absolute risk (10 years CHD risk < 15%). Low absolute risk particularly among young adults does not ensure a lifetime of low risk because the number and severity of metabolic risk factors worsen with aging. Hence periodic monitoring is needed to assess the changes in risk status over time.

Although JBS risk prediction chart is a valuable tool in predicting CHD risk, it has some limitations. This arises from the fact that the scoring system is derived from Framingham heart study participants which differ from the subjects considered in this study by their geographical location and ethnic group. However, an advantage of using JBS is that it suggests priorities for instituting primary prevention strategies.

This study comprises of patients between 40-65 years of age which could benefit greatly from the primary preventive measures.

The number of female subjects in the study is higher than male subjects, because male subjects have higher chance of being diagnosed with CHD than females in this age group. As reported by Paranjape et al. (2005) women in the age group of 20–50 are shown to have much less susceptibility to coronary heart disease and other atherosclerotic diseases as compared to men. The findings of this study

also showed significantly higher calculated 10 years risk of CHD for male than female (P < 0.05). There is no statistical difference between

the different sexes and races with regard to risk stratification (Table 2).

According to the Framingham Heart Study, obesity increases an individual’s risk of CHD by 104 percent. This is because obesity raises blood cholesterol and triglyceride levels, and reduces HDL levels which lead to more plaque build up in the arteries. Obesity increases blood pressure and can lead to diabetes. A total 17% of the subjects (n=18) were found obese and n=28 (27%) were overweight. As reported by Gotto (2002) and NHLBI (2005) patients who are under high risk for CHD but had BMI > 25kg/m2 would require total life style changes (TLC).

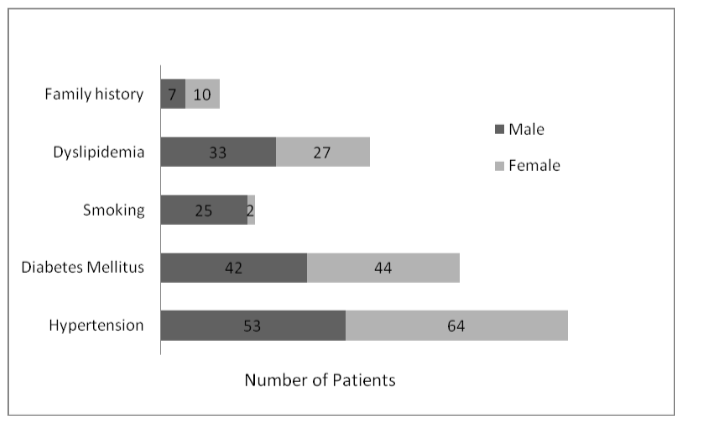

Ezzati et al. (2005) reported that smoking contributes to high prevalence rate in CHD mortality and is mostly related to men in all regions and it. Similarly in this study, 92.5% (n=25) of the smokers in the study were male (Figure 1). Rapid reversal of CHD mortality is observed epidemiologically after smoking cessation, even in patients with established CHD. Thomson & Rigotti (2003) recommended to give due emphasis to efforts to reduce smoking prevalence.

In this study, 90% subjects were having hypertension (Figure 1) and according to the study done by Lee et al. (2000) in Singapore to compare the relatively different contributions of risk factors to the risk of CHD between Asians and Caucasians showed that hypertension is the most important risk factor for CHD in Asians.

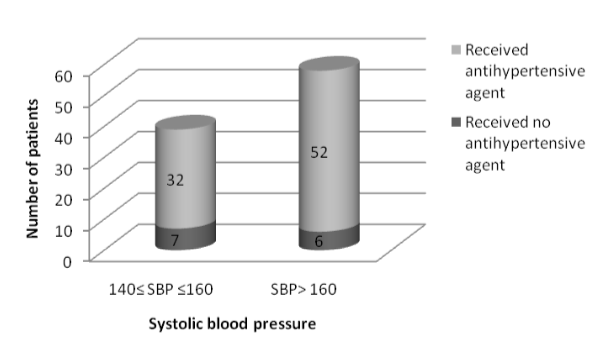

Out of 117 hypertensive patients in this study, 88% (n=100) received antihypertensive therapy. According to the Joint British recommendations on prevention of CHD, life style advice and drug treatment should be given for a patient with SBP is ≥ 160 mmHg or DBP ≥ 100 mmHg, regardless of absolute CHD risk. In this study 10% (n=6) of the subjects with SBP ≥ 160 were not on any medication (Figure 2).

As indicated by Benner et al. (2001), large prospective randomized trials have confirmed the importance of blood pressure control in reduction of cardiovascular mortality and morbidity, irrespective of the class drugs used.

Diabetes too increases the risk of developing CHD. ATP III indicated that most patients with diabetes are at high risk even in the absence of established CHD. For effective CHD prevention it is recommended that optimal glycaemic control should be reached (HbA1c< 7%). Results from this study showed that subjects had a significantly different HbA1c level (t (87) =3.387, P< 0.05) from the target level and the majority of subjects were having HbA1c level greater than 7 %.

A study by Hu et al. (2001) shows that type II diabetics have the same cardiovascular risk as non- diabetics post myocardial infarction, suggesting a strong case for all patients with type II diabetes to receive cholesterol lowering therapy.

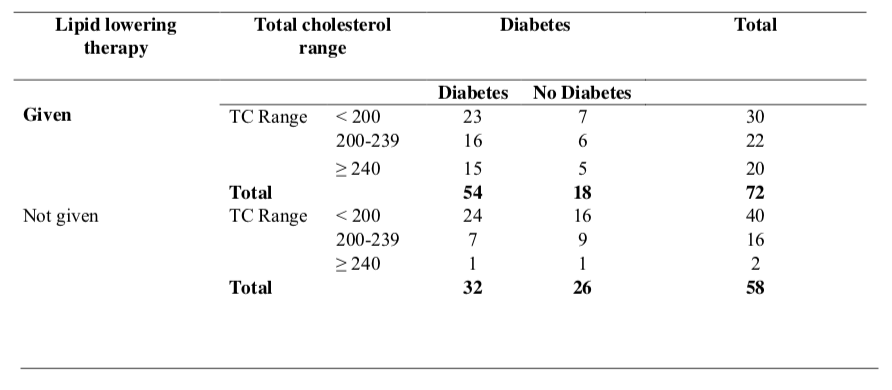

The findings of this study showed a significant association between diabetes and lipid lowering therapy use (P < 0.05). Among diabetic patients, 62%, (n=54) received lipid lowering agent. On the

contrary, 37% (n=32) of the diabetic subjects did not obtain any lipid lowering agent. Only 3% (n=1) of these patients had TC ≥ 240mg/dL while 22% (n=7) and 75% (n=24) had a borderline TC (200-239 mg/dL) and desirable TC (< 200mg/dL) respectively (Table 4).

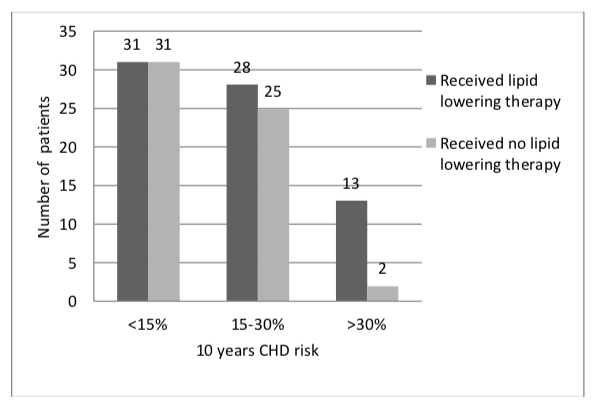

Dyslipidemia is the third prevalent risk factor after hypertension and diabetes occurring in 46.2% (60) of the subjects. Lipid lowering therapy was given to 87%, 53% and 50% of subjects with 10 years risk of CHD > 30%, 15-30 % and < 15% respectively. The Joint British guideline recommended all patients with 10 years CHD risk ≥15% should receive lipid lowering therapy.

Law et al. (2003) reported that lipid lowering therapy (statin) is effective in decreasing coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke risk, both in primary and in secondary prevention.

The benefit of treatment with a statin is observed among people with annual levels of risk as low as 1%. Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group (2005) suggest that even at this level of risk statin treatment is cost effective within the terms of reference applied to other medical treatment.

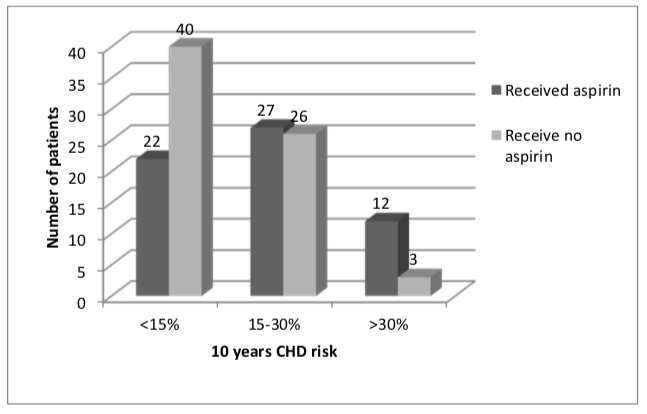

Aspirin uses for primary prevention have been evaluated in three major meta-analysis conducted by Hyden et al (2005), Sanmuganathan et al. (2001) and Ridker et al (2005). The use of aspirin for the primary prevention of CHD was reported to be beneficial among patients with high cardiovascular risk. Furthermore De Backer et al. (2003) recommends aspirin for primary prevention in adults with diabetes or well-controlled hypertension and in men at high risk > 20%. However the benefits of aspirin in patients with lower risk remains controversial.

In this study, aspirin use increased with increase in 10-year CHD risk level (Table 6). The association of the risk level with use of aspirin was statistically significant; (X2=10.19, df= 2, P < 0.05). Moreover, use of aspirin is strongly associated with presence of diabetes (X2=4.397, df= 1, P < 0.05) and dyslipidemia.

Conclusion

Risk factor modification is crucial to reduce the morbidity and mortality related to CHD. This study reveals that the most prevalent risk factor for CHD was hypertension and this may be attributed to healthcare factors including under diagnosis or inadequate control of previously diagnosed hypertension. Primary prevention measures are highly recommended for those with higher risk groups for each risk factors modulated. However, not all treatment eligible patients received primary preventive measures as observed in this study. Therefore, future evaluation into the reason for suboptimal primary prevention practice is required to improve the management practice.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge the medical ward staff of HUKM and record room personnel for their invaluable assistance.

References

- World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2001: Making a Difference. Geneva: WHO.

- National Heart Association of Malaysia (NHAM).2009.Heart Disease Top Killer in Government Hospitals.www.malaysianheart.org/article.php?aid=42.

- Gordon T, Castelli WP, Hjortland MC, Kannel WB, Dawber TR. Predicting coronary heart disease in middle-aged and older persons: the Framingham study. JAMA. 1977;238: 497-499.

- Ho JE, Paultre F. & Lori M. 2005. The gender gap in Coronary Heart Disease Mortality: Is there a difference between Blacks and Whites? Journal of Womens Health 2(14):117-127.

- Jeannette L, Derrick H, Kee SC, Suok KC, Bee YT & Kenneth H. 2001. Risk factors and incident coronary heart disease in Chinese, Malay and Asian Indian males: the Singapore Cardiovascular Cohort Study. Int J Epidemiol 30:983-988.

- NCEP. 2001. Executive Summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA 285:2486–2497.

- Joint National Committee. The Fifth Report of the Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Bethesda, Md: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; 1993:49. NIH publication. 93–1088.

- Joint British recommendations on Prevention of coronary heart disease in clinical practice. 2000. JBS recommendations on Prevention of CHD in clinical practice: summary. British Cardiac Society, British Hyperlipidemia Association, British Hypertension Society, British Diabetic Association. BMJ 320:705- 708.

- Larabie, L.C. 2005. To what extent do smokers plan quit attempts? Tobacco Control 14:425-428.

- Khoo KL, Tan H, Khoo TH. 1991.Cardiovascular mortality in peninsular Malaysia: 1950-1989. Med J Malaysia. 46:7-20.

- NHLBI. 2005. Your Guide To Lowering Your Cholesterol with TLC. National Institute Of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). NIH Publications No 06-5235.

- Paranjape SG , Turankar AV, Wakode SL , Dakhale GN. 2005. Estrogen protection against coronary heart disease: Are the relevant effects of estrogen mediated through its effects on uterus – such as the induction of menstruation, increased bleeding, and the facilitation of pregnancy? Medical Hypotheses 65(4): 725-727.

- Ezzati, M., Henley, S.J., Thun MJ. & Lopez AD. 2005. Role of smoking in global and regional cardiovascular mortality. Circulation 112(4):489-497.

- Thomson CC & Rigotti NA 2003. Hospital and Clinic Based Smoking Cessation Interventions for Smokers with Cardiovascular Disease. Progress in Cardiov Dis 45(6):459-479.

- Lee WL, Chepung AM, Cape D, & Zinman B. 2000. Impact of diabetes on coronary artery disease in women and men: a meta analysis of prospective studies. Diabetes Care 23:962-968.

- Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, Keane WF, Mitch, WE, Parving, H.H., Remuzzi G, Snapinn SM, Zhang Z. & Shahinfar S. 2001. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. RENAAL Study Investigators. N Engl J Med 345(12):861-869.

- Nayaran P & Man AJ. 1998. Clinical pharmacology of modern antihypertensive agents and their interaction with alpha-adrenoceptor antagonists. Br J Urol 81(1):6-16.

- Verdecchia P, Reboldi G, Angeli F, Gattobigio R, Bentivoglio M, Thijs L, Staessen JA & Porcellati C. 2005. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and calcium channel blockers for coronary heart disease and stroke prevention. Hypertension. 46(2):386-92.

- Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Solomon, CG, Liu S, Willett WC, Speizer FE, Nathan DM & Manson JE 2001. The impact of diabetes mellitus on mortality from all causes and coronary heart disease in women: 20 years of follow-up. Arch Intern Med 161(14):1717-23.

- Sowers JR. 2003. Effect of statins on vascularature: implication for aggressive lipid management in cardiovascular metabolic syndro-me. Am J Cardiol 91:14B-22B.

- Law MR, Wald NJ, Rudnicka A R. 2003.Quantifying effect of statins on low density lipoprotein cholesterol, ischaemic heart disease, and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ .326.1423– 1427.

- Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. 2005. Cost effectiveness of simvastatin in people at different levels of vascular disease risk: economic analysis of a randomised trial in 20536 individuals. Lancet 365.1779–1785.

- Hayden M, Pignone M, Phillips C & Mulrow C. 2002. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 136:161-172.

- Sanmuganathan PS, Ghahramani, P, Jackson PR, Wallis EJ & Ramsay LE 2001. Aspirin for primary prevention of coronary heart disease: safety and absolute benefit related to coronary risk derived from meta-analysis of randomised trials. Heart 85:265–271.

- Ridker PM, Cook NR, Lee IM, Gordon D, Gaziano, JM, Manson, JAE, Hennekens CH & Buring, JE 2005. A randomized trial of low-dose aspirin in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in women. N Engl J Med 352:1293–1304.

- De Backer, G., Ambrosioni, E., Borch-Johnsen, K., Brotons, C., Cifkova, R., Dallongeville, J., Ebrahim, S., Faergeman, O., Graham, I., Mancia, G., Cats, V.M., Orth-Gomér, K., Perk, J., Pyörälä, K., Rodicio, J.L., Sans, S., Sansoy, V., Sechtem, U., Silber, S., Thomsen, T. & Wood, D. 2004. European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Third Joint Task Force of European and other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of eight societies and by invited experts). European Society of Cardiology. American Heart Association. American College of Cardiology. Atherosclerosis 173(2):381-91.

Please cite this article as:

Semira Abdi Beshir and Rosnani Hashim, Calculated 10 Years Risk of CHD: Primary Preventive Measures in Medical Ward PPUKM (University Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Centre). Malaysian Journal of Pharmacy (MJP). 2011;9(1):336-344. https://mjpharm.org/calculated-10-years-risk-of-chd-primary-preventive-measures-in-medical-ward-ppukm-university-kebangsaan-malaysia-medical-centre/