Abstract

A cross-sectional study was conducted among pharmacy students to determine factors influencing their choice of work place and to evaluate whether a one-year hospital pre-registration training programme had any effect on these choices. Questionnaires were distributed to graduating students at the School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia. The questionnaires were again sent to the same group of students by post at the end of their pre-registration training year. The response rate during the follow-up stage was 46%. Results indicated that students in the survey were more interested in independent and chain community pharmacies compared to other practice settings. Students’ choices of first place of practice appeared to be influenced by both intrinsic and extrinsic job factors. Our findings did not show major changes in students’ preferences for practice sites before and after the hospital pre-registration period. This information is expected to be useful for pharmacy employers.

Introduction

In this day and age, pharmacists play an essential role in educating patients regarding drug therapy as patients become increasingly responsible for their own health care. Community pharmacists are the health care professionals most accessible to the public [1]. The community setting is a platform for the pharmacist to project himself beyond the traditional image of being simply a “drug supplier” in that he is able to provide pharmacotherapeutic counselling to patients, apart from general health care information to the public. This is in line with Hepler and Strand’s concept of pharmaceutical care [2].

However, this professional expertise will only be fully utilised if the public is aware of and understands the role played by the pharmacist in the community. Hence, this exploratory study was conducted to ascertain the public’s awareness regarding the community pharmacy profession and pharmacists.

Aim

The aim of this study is to examine the public’s awareness about community pharmacy and pharmacists, in a selected subset of the Malaysian population.

Method

Study design

This public opinion survey was conducted using a structured interview technique, in which the respondents were asked questions by trained researchers (25 undergraduate students and 1 pharmacist). It took place over a 4-day period in August 1997, during the University of Malaya Convocation Festival. Visitors to the Pharmacy booth who appeared to be over 18 years of age were approached about participation in the survey. The sampling method used was that of convenience sampling. Only those who agreed (97.9%) participated in the study, with each interview taking approximately 8 to 10 minutes to complete.

Questionnaire

A structured questionnaire was used. Apart from the portion relating to the demographic profile of the respondents, there were altogether 10 questions focussed on the following aspects:

- the respondents’ general awareness of pharmacists and their places of work

- the purchasing pattern of respondents in relation to pharmacies, sinseh (traditional Chinese medicine practitioner) shops and other places

- the awareness of services offered by community pharmacies such as treatment of minor ailments, screening tests and advice on medications.

Each question had pre-formulated responses. The questionnaire designed by the research team was piloted with a sample of 25 staff members of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Malaya.

Data analysis

The data was entered into a worksheet and analysed using Microsoft Excel®. A scoring system was practised as follows:

- For any question requiring either a “Yes” or “No” or “Unsure” response, only the positive response was given a score of 1, whilst any of the other two responses was awarded a score of 0 each. As an example, for the question “Have you heard of the term ‘Pharmacist’?” a “Yes” response was scored as 1.

- For any question requiring the choice of one or more than one answer, only the answers deemed appropriate was given a score of 1 each and a deduction of 1 was made for each inappropriate answer, with the lowest possible final score of 0 for any question. As an example, for the question “To whom would you go for advice on medicines?” where more than one answer may be given, a respondent who chose “Pharmacist”, “Doctor” and/or “Nurse” was given a score of 1 for each of the answers with a deduction of 1 if “Sinseh” was also selected along with any of the appropriate answers. If “Sinseh” was the only answer selected, the respondent received a final score of 0 for that question.

A total score was computed for each respondent, ranging from a possible minimum of 0 and a maximum of 24. The scores achieved were arbitrarily categorised into poor (<11), fair (11 – 14), good (15 – 19) and excellent (>19) levels of general knowledge regarding community pharmacy and pharmacists.

Result and Discussion

General

appropriateness of the responses given to the questions administered.

There were 561 respondents, who were mainly Malaysians (97.5%). The ethnic representation was 59% Malays, 29% Chinese and 9% Indians. The majority (61.5%) of the respondents were between 18 – 25 years old with 18.2% and 17.1% aged between 26 – 35 years and 36 – 50 years respectively. In terms of gender distribution, 41% of the respondents were male. The composition of the respondents include undergraduates (55.1%), professionals (16.6%), non-professionals (20.3%), school-going students (3.7%), postgraduate students (2.3%), housewives (1.1%) and pensioners (0.9%). The majority (75%) of respondents lived in urban areas.

The respondents’ scores ranged between 3 to 21 out of a possible maximum of 24. The majority of the respondents obtained scores in the “fair” (48%) and “good” (39.6%) categories. The mean score was 13.7 and the mode was 14 (both in the “fair” category). Figure 1 reflects an almost normal distribution. The generally fair scores achieved by the respondents were not unexpected with almost three-quarters (74%) of them either undertaking or had attained a tertiary level of education. There were only four respondents who obtained excellent scores: two were undergraduates, one was a housewife while the other was a sales executive. Surprisingly, no professional achieved an “excellent” score. The scores for the different occupations, genders and ethnic groups were not significantly different based on the student’s t-test (p>0.05).

Public image of pharmacists

The respondents were assessed on their level of awareness of the term “Pharmacist” as well as the nature of work and workplace of a pharmacist. Most respondents (93.6%) had heard of the term “pharmacist” while 89.7% and 88.2% respectively, thought they knew what the pharmacist did and where the pharmacist worked. However, the following question, which required the respondents to choose the workplace of the pharmacist, disproved the above notion. While most respondents associated the pharmacist with the retail sector, hospitals, academia and factories, a shocking 77.4% associated pharmacists with doctors’ clinics and 17.5% with farms! [Figure 2]. Obviously, the respondents had heard of the term “pharmacist”; however, their awareness of a pharmacist’s role in the community was not completely accurate. The association with working in a doctor’s clinic suggested a confusion between the roles of dispensers and pharmacists. Farms were also associated with pharmacists, possibly due to the perceived similarity between the words “pharmacy” and “farm”. Most of the study population (91.1%) associated pharmacists with the community or retail pharmacies and less with hospitals, factories and pharmaceutical trading houses. This confirms that community pharmacists have a higher visibility and hence would be in a better position to disseminate information and influence public opinion on pharmacy.

In this survey, quite a large proportion of the people interviewed (77.2%) identified the university as a place of work for pharmacists. This was not surprising since this study was conducted on university grounds during the convocation festival. This percentage would, however, be expected to be smaller if the study was conducted in the general population.

Sale items associated with community/retail pharmacies

The familiarity of the respondents with the pharmacy and sinseh shop was established before the respondents were asked questions on their purchasing patterns at these two places. It was found that 88.4% of the respondents had visited a pharmacy before as compared to a sinseh shop (67.4%).

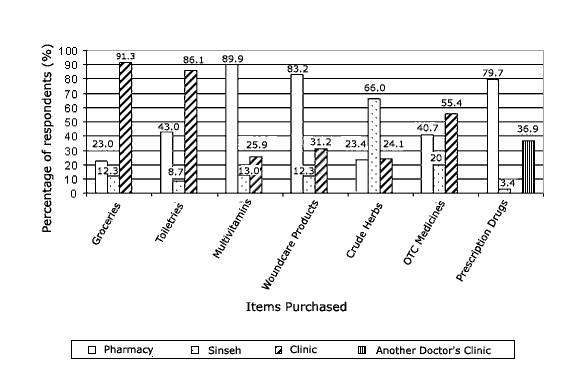

The respondents were interviewed on their preferred places for purchasing groceries, toiletries, health supplements, woundcare products, crude herbs, over-the-counter (OTC) medicines and prescription drugs, with more than one response permitted for these questions. It was seen that a pharmacy was generally associated with multivitamins (89.9%), woundcare products (83.2%) and prescription drugs (79.7%), as displayed in Figure 3. The majority of the respondents (55.4%) preferred to buy OTC medicines from places other than the pharmacy and the sinseh shop. Could price and accessibility be a contributing factor? In comparison, a public opinion survey of community pharmaceutical services in Malta [3] revealed that almost 31% of their study population visited a pharmacy primarily to purchase prescribed medication while only 23.3% did so mainly to obtain OTC products.

It was interesting to note that almost 40% of the respondents would also purchase prescription medicines from another doctor’s clinic having acquired the prescription from a clinic or hospital. This is certainly an alarming situation as it indicates an evident lack of awareness of the function of a community pharmacy.

Community pharmacies are also often associated with the sale and supply of products other than drugs and medical supplies. Fortunately, although a pharmacy was not the favoured place the respondents would go for the purchase of groceries and toiletries, a certain percentage of the respondents do associate a pharmacy with these items (23% and 43% respectively). There is certainly justification for the diversification of sales range for these community pharmacies. Profitability, competition and service are probably the motivation for these premises to offer items other than drugs and medical supplies. Hence, a significant proportion of the respondents inevitably perceived the pharmacies that they frequent as a “convenience store”.

Services offered by community/retail pharmacies

The final section surveyed the respondents’ preferences in sourcing treatment for minor ailments and screening tests [Figure 4] and advice on medications [Figure 5]. The respondents were given a choice of a pharmacy, clinic, sinseh shop and hospital for the treatment of minor ailments such as cough, cold or minor aches and pains, where more than one answer may be given. Although treatment for minor ailments can be obtained at the community pharmacies after consultation with the pharmacists, the majority of the respondents (73.6%) preferred the doctor’s clinic, with only 41.7% selecting the pharmacy. Should we be surprised? This phenomenon was also reflected in a survey conducted in Malta [3], where respondents were reported to more likely consult their doctor or self-medicate for the treatment of minor ailments rather seek advice from the pharmacist. Similarly, Hargie et al (1992) also reported that in Northern Ireland, general practitioners were the first preference for the majority of the patients with regards to the treatment of minor conditions [4].

Correspondingly, when the respondents were questioned on the places associated with offering screening tests, the popular choices were the clinic (76.7%) and the hospital (59%). Only 11.2% of respondents would go to a pharmacy for screening tests. Some community pharmacies do offer services such as screening tests to the public. This study indicates that perhaps a majority of the public is unaware of such services being available in the community pharmacies and thus would prefer to go to general practitioners and hospitals for the treatment of minor ailments as well as for screening tests. The next question quizzed the respondents on whom they would go to for advice on medications, where more than one answer was permitted. It was disappointing to note that only 49.4% of the respondents would go to a pharmacist for information concerning medicines, compared to 84.1% of the respondents who would choose a doctor. [Figure 5]

Thus, although pharmacists are deemed to be experts on drugs [1], it is unfortunately not perceived as such in the eyes of the majority of the respondents interviewed. This result is in concurrence with the findings of a recent survey conducted in Northern Ireland by Bell et al (2000). The latter revealed that although the majority of those interviewed (87.8%) considered pharmacists as experts in the field of medicines, however, only 64.6% reported that they would talk initially to a pharmacist regarding information or advice concerning medicines [5]. One possible reason for this situation may be the lack of rapport between the patients/public and the pharmacists as compared to doctors or nurses. Another reason may be the fact that pharmacists are often viewed by the public as business people concerned with making money rather than health-oriented care-driven professionals. Two surveys conducted in Northern Ireland [4][5] found that about one-third of their study populations harboured that perception.

In examining the situation in other countries, it was found that in India, community pharmacies were not perceived to be respectable [6]. In Great Britain, on the other hand, two national representative surveys had demonstrated that the public interviewed do perceive pharmacists as appropriate advisers for common ailments but not for more general health matters [7]. In the United States of America, the 1998 Schering Report XXI showed strong gains in terms of the patients’ perception of community pharmacists, compared to a similar 1978 survey [8]. It is imperative that the Malaysian public should be made aware of and understand the role of pharmacists in the community, in order for the profession to realise its full potential and the public to benefit from the expertise available. Improved social interactions between the public and the pharmacists, in particular personal attention in relation to advice on the treatment of minor ailments, self-care and dispensed medications, is probably the key to increasing the level of public awareness.

Limitations of the study

Admittedly, the study population used in this survey was biased towards the more educated and urban portion of the Malaysian public, specifically those who visited the Pharmacy booth during the University of Malaya Convocation Festival. This study was, however, designed for a quick snap-shot of this subset’s perception of community pharmacies and pharmacists with the thought in mind that if this subset demonstrates a lack of awareness, then it is most unlikely that the less educated and rural subsets of the Malaysian public will be any better. Another limitation of this study was its setting that did not permit a more extensive line of questioning.

Conclusion

Although this study was conducted in a selected subset of the population, it does offer a baseline relating to the public perception of community pharmacy and the pharmacy profession in 1997, at least in relation to the more educated and urban section of the public. Of late, with increasing attention in the mass media on the issue of dispensing separation and the role of the pharmacists, particularly in the community, the public’s perception towards the pharmacists may have since improved. Its significance or the lack of it can only be demonstrated through the conduct of a second survey, preferably using a bigger study population and a stratified random selection of the interview sites representing the various states/territories in Malaysia. Nonetheless, the findings of this survey have clearly impressed the urgent need for the pharmacy profession, particularly the community pharmacy sector, to project itself in the eyes of the public as uniquely qualified professionals on drugs, and a reliable source of unbiased information as well as advice on medications and general health care.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all the 25 undergraduate students, who conducted the interviews for this study after undergoing the training provided, and Mr. Mohamed Azmi bin Ahmad Hassali for his assistance in the procurement of the literature.

References

- World Health Organisation. The scope of pharmacy and the functions of pharmacists. In: The role of the pharmacist in the health care system. Report of a WHO Consultative Group; 1988 Dec. 13-16; New Delhi.

- Hepler CD, Strand LM. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am J Hosp Pharm 1990; 47: 533-43.

- Cordina M, McElnay JC, Hughes CM. Societal perceptions of community pharmaceutical services in Malta. J Clin Pharm Ther 1998; 23: 115-26.

- Hargie O, Morrow N, Woodman C. Consumer perceptions and attitudes to community pharmacy services. Pharm J 1992; 249:688-91.

- Bell HM, McElnay JC, Hughes CM. Societal perspectives on the role of the community pharmacist and community-based pharmaceutical services. J Soc Admin Pharm 2000; 17: 119-28.

- Singh H. India: Retail pharmacy not respectable. Pharm J 1982; 228:145.

- Anon. Public faith in pharmacist’s advisory role. Pharm J 1985; 235:177.

- Anon. Pharmacists gain in public esteem. Am Drug 1999; 216:29.

Please cite this article as:

Hadida Hashim, Ahmad Mahmud, Lim Wai Hing, Lum Peck Yoong, Natasha Mohd. Yusof and Tang Yoke Bun, Public Awareness of Community Pharmacy and Pharmacist. Malaysian Journal of Pharmacy (MJP). 2001;1(1):22-28. https://mjpharm.org/public-awareness-of-community-pharmacy-and-pharmacist/